Cultural Analysis, Volume 18.2, 2020

The Black Dog: Origins and Symbolic Characteristics of the Spectral Canine*

Abstract: The Black Dog is a folklore staple, easily recognizable by its mangy back hair, ominous presence, and ember-filled eyes. It is also a symbolic narrative tool in pop culture, as seen in Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles. However, it did not emerge from a void; Black Dog lore stems from Ulysses’ Argos, continues through the Aesopian dogs, and borrows thematic nuances from werewolves, but its foundations stand firmly on the backs of mythology’s noble hounds: Cerberus and Fenrir, who provide literary and psychological symbolism via their representation of the subconscious triumvirate (superego, ego, and id), temporal triumvirate (past, present, and future), and the Jungian shadow. Furthermore, Cerberus’ role—whose image, I argue, is most influential—as a guardian, not of the boundary between life and death, but between reality and fantasy, is the primordial father of the allegory of self- perpetuating imagination, of which the Black Dog is a vital fragment.

Keywords: Black Dog, cultural chaos, fantasy, myth, narrative, Cerberus, symbolism

____________________

Introduction

In the 1943 winter-issue of the Hosier Folklore Bulletin, Robert G. McGuire, a local journalist, recounts a curious story of a man named Johnnie, who at the time of the telling of his tale was older. While a young lad in Detroit, Johnnie accompanied his mother across the Irish section of the city, dubbed Corktown, to visit her friend, Mary. Johnnie recounts,

We'd not gone far…before Mother said, "Something's wrong, Johnnie," and a few steps after that, we saw a black dog running in front of us. He was a great big son of a gun, and all black as tar. First, he'd run before us and then behind us, but he never left us alone for a minute. "We're turning back," says Mother, "for when my father died, a black dog ran along the roof and howled the whole night." (McGuire 1943, 21)

The next day, someone murdered Mary; witnesses sighted a black dog at the scene.

Such stories are uttered throughout Western Europe and within immigrant communities in the United States. Great Britain is often the setting of these tales, many of which were compiled by folklorist Ethel Rudkin of Lincolnshire and published in a 1938 issue of Folklore under the title “The Black Dog.” Her study—unnoticed by academia and overshadowed by research on other more prominent folktales, such as the Little Red Riding-hood, Krampus, or Snow White’s Mirror—is essential in understanding why the mind is unwilling to comprehend a commonplace animal such as a dog within the context of the supernatural.

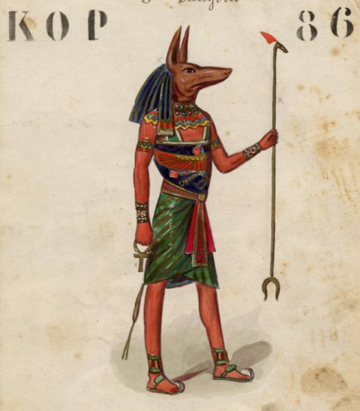

I hope to furnish Miss Rudkin’s observations their rightful dues and will do so by analyzing what the Black Dog is, why its symbolism matters, and the origins of its form through the study of literature’s royal dogs: Ulysses’ faithful Argos, Hades’ hellish Cerberus, and Loki’s fiendish Fenrir. Along the way and to understand how their tropes relate to Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung’s idea of duality and the shadow, I will detour into lore on Aesop’s dogs, werewolves, and Anubis, the Egyptian judge of the dead. However, before I do so, a quick note on the structure of this paper: after a short introduction, I will describe the Black Dog—physical portrayals and variants, associated locations with the creature, its role in folklore—then look at its derivative symbolism and aspects taken from Argos, Anubis, the werewolf, Cerberus and, finally, Fenrir. All the while, I will weave the psychological and narrative concepts expressed by Freud, Jung, and Joseph Campbell, among others, into the spectral tapestry that is the ebony canine.

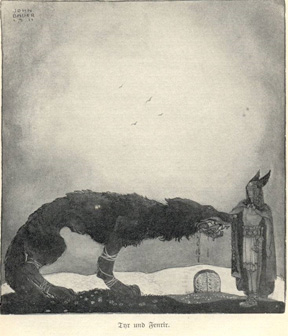

Regarding the methodology of this study: besides looking at such primary sources as Ethel Rudkin’s commentary, I am using Mark Norman’s recent work on Black Dog encounters in Great Britain. Theo Brown’s 1958 work on the importance of reoccurring Black Dog locations such as crossroads, churchyards, borders, supplements these studies. By drawing on popular retellings of Aesop’s Fables, Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy, and Ovid’s The Metamorphosis, I give context to Black Dog’s symbolism via its progenitors. I chose popular retellings over academic ones (although I do use them in some instances, for example, to better this paper’s narrative flow) because popular retellings remain in the public’s collective imagination more so than scholarly ones. Additionally, they are concise without much analytical meandering, which is helpful when recounting an essential mythological beat—for example, the chaining of Fenrir—as clearly as possible without the need to dive into what the author of the academic retelling meant by analysis x, y or z.

Furthermore, the Black Dog is a folktale staple drenched with folklore; hence it is only appropriate to adhere to the popular retellings. All theoretical works, such as Jerold Franks, “Loki’s Mythological Functions in the Tripartite System,” Michael Haase’s “Nietzsche and Freud: Questions of Life and Death,” or Marina Warner’s Once Upon a Time are meant to enhance and illuminate the ancient symbolism of Cerberus and Fenrir, and provide a thematic mirror to that of the Black Dog—reflecting its past in the present while forecasting its future. The works of Freud (The Uncanny or Civilization and its Discontent) and Jung (Man and His Symbols or Modern Man in Search of a Soul) are meant to enrich the connection between the Dog’s symbolism and the trickster archetype in the age of cultural chaos—a term defined below. Furthermore, the essence of these texts is present throughout this article.

Regarding the cited online sources: each of them is written by an authoritative author, including two Egyptologists, a scholar of Norse mythology, the staff at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the staff of an award-winning occult encyclopedia, who present their work with credible sourcing. Additionally, these online sources act as secondary supports for academic foundations that form the base of this work. Regarding the presentation, I wish to keep it in the style of the works that comprise this paper. In other words, the format and style are complementary to its subject matter and stays professional throughout.

I invite all those who read this work to contact me if they so choose, to further the dialogue concerning the Black Dog and its role in contemporary storytelling. With that out of the way, let me begin with defining, dissecting, and deliberating this paper’s primary subject matter, and there is no better place to start this analysis than by looking at the most famous contemporary version of the Black Dog: Sirius Black.

Characterizing the Black Dog

When J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban were published in 1999, it became an instant classic, selling, as of the 2020 count, approximately 65 million copies (Atkins 2020, 1). Among the cast of colorful characters was Harry Potter’s godfather, the aforementioned Sirius Black, who was capable of transforming into a scroungy black dog, or as professor Trelawney, Harry Potter’s Divination lecturer, explained, “The Grim, my dear boy, the Grim…The giant, spectral dog that haunts churchyards. My dear boy, it is an omen—the worst omen—of death” (Rowling 1999, 107). Though rare, black dog transformations do appear, and there is some precedent for them in folklore, a fact detailed below.

While prof. Trelawney keeps in line with one of the traditional slants on the Black Dog as a premonition of doom. The hound’s history and inspirations suggest that the apparition is a symbol of human indecisiveness, fear of failure, and time. When Prisoner of Azkaban received a 2004 silver screen adaptation, the image of the Black Dog engraved itself onto the collective imagination of a generation through Warner Brothers’, the film’s distributor, inspired merchandising campaign. While Black’s plush canine alter-ego sold well, the origins of the creature’s image and its allegory were lost in the resonant whirlwinds of popular culture.

Illustration 1. The coal-black Hound. Illustration by Sidney Paget. From The Hound of the Baskervilles, by Arthur Conan Doyle, 1901. CC-PD-Mark.

Since the Middle Ages, both gossiping serfs and high-minded nobles whispered of the shadow hound that emerged from the abyss during the depths of night. Its legend grew, especially in the United Kingdom. Popular among Renaissance and Victorian storytellers—be they the crones of the village or court jesters—fairytales, local myths, and anecdotes of the woodland witches hiding amid civilization tended to have a sinister familiar in their narratives. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle took his inspiration for the now famous 1902 detective story The Hound of the Baskervilles from the English folk legend. His description of the “foul thing, [the] black beast, shaped like a hound” with “hell-fire shooting from his mouth and eyes” (Doyle 2015, 12) has been reported hundreds of times throughout the British Isles. The creature’s notoriety is such that “photographer and researcher Nick Stone…has so far collected between 400 and 500 accounts” (Prickett 2015, 1) of the creature, mapping out and posting all sightings online (Stone 2015, 1), while author Mark Norman cataloged 719 such sightings (Norman 2015, 185-242). Even the creature’s numerous names—among them, Padfoot and Gytrash, which come from Gaelic for “the curious sound made by the hound’s footfall” (Norman 2015, 20)—are plentiful in literature, one prevalent example being Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre.

Besides being a black dog, what else defines the creature? Theo Brown, along with Ethel Rudkin, and W.P. Witcutt, paint a very detailed image of the specter. What is called Barguest, Shuck, Black Stag, Trash, Shriker, or Hooter, “is always black, and is always a dog and nothing else. It may appear like a normal dog, sometimes a retriever, smooth or curly-coated” (Brown 1958, 178) sometimes “smooth and gleaming” but “more often shaggy, like a bear” (Brown 1958, 180). Furthermore, the Black Dog “is often heard, for when he disappears into a hedge, the leaves rustle loudly, or the ‘twigs crackle as if they were afire.’ In one description, his coat is wiry ‘like pig-bristles’—in another, he is ‘tall and thin with a long neck and pointed nose” (Rudkin 1938, 130). The creature “varies in size from normal—so that it is mistaken for a real dog—to enormous” (Brown 1958, 178). W.P. Witcutt adds that some describe it as “black with staring eyes” (Witcutt 1942, 168).

In certain areas, such as Suffolk and Norfolk, England, the creature is “frequently one-eyed…and always ominous;” meanwhile in Westmorland, “it…appears without a head” (Brown 1958, 176). According to accounts compiled by Rudkin, the Black Dog is

always ‘table high,’ sometimes spoken of as being ‘as big as a caulf’ (sic) which often produces a muddled idea as to whether he is a calf or a dog… No matter how dark the night, the Dog can be seen because he is so much blacker. He seems to have a tendency to appear on the left-hand side of the spectator, he crosses the road from left to right, and he is definitely looked on as a spirit of protection. (Rudkin 1938, 130)

Brown seconds the blackness of the Dog in an account that states, “The Lincolnshire dog always looks blacker than the blackest night, can cross water, but does not cross parish boundaries, though he sometimes seems to be connected with them” (Brown 1958, 179).

Its habitat too is a curious thing, as it is split into three sorts: 1) areas near water, such as rivers, streams, ponds, coasts, or bridges, with a total of over 100 recorded hauntings (Brown 1958, 182); 2) roads and crossroads, which Brown states, “seem to be the natural home of the Black Dog” with at least 55 examples cited in his study, 25 of which were in Lincolnshire alone (Brown 1958, 182); and 3) churchyards and cemeteries, which are often home to the Barguest variant that “goes out of its way to show the beholder it is no normal dog, but a monster from another world, having no one definite form—though it favors the black dog—and is malevolent in character” (Brown 1958, 178). Witcutt notes that these Black Dogs “guard the graves of those who died by violence” (Witcutt 1942, 167). Grave guardianship goes hand in hand with the accounts given by Brown, where

a number of isolated burials are haunted by Black Dogs, such as fallow old battle-sites. Jacobite graves round Swinscoe, Staffordshire, are haunted by a Black Dog. This, of course, is a symbol of the person buried there. Two gallows sites are also haunted. One at Tring, Hertfordshire, commemorates a man who falsely accused a woman of witchcraft, so that she was drowned in 1751, and he was afterwards hanged near the spot. Which is the dog—the witch or the man? The other gallows site is at Castle-town, Isle of Man. (Brown 1958, 185)

While folkloric accounts keep the territoriality of the Dog rather vague, with parish borders marking its broad haunting grounds, the thousand-plus accounts gathered by Mark Norman and Nick Stone suggest that, generally, the same Dogs are seen around the same areas, implying an incomplete region-wide dominance of specific Dogs. Rudkin’s research seconds this assertion.

Witchcraft is a rare facet of the Black Dog mythos, being a common misconception popularized by Bram Stoker’s Dracula, among others, that magic about brings forth the creature. While cases exist where “the symbol of the Black Dog is used by the Devil, by the familiar, and by the witches themselves in transformation” (Brown 1958, 178), the likelihood is that the image of the Black Dog is connected to witchcraft and not the Black Dog itself. Brown notes that “[a]t Stogursey in Somerset, Miss Ruth Tongue has noted an instance where the witch has continued her transformation in death, and it is generally understood that the Black Dog is the witch herself” (Brown 1958, 178). This occurrence suggests that a black dog and the Black Dog are separate entities: one being a human transformation, the other a supernatural entity in its own right. Fairy tales are one example of this folkloric precedent, where villainous witches transform into dogs or wolves. In the case of the Slavic fairytale ‘A Tale of Trasovich Ivan, the Firebird and the Gray Wolf,’ it is hinted that the wolf aiding the noble Ivan is an angel or Fate transformed (Suchanek 2001, 175-176).

Furthermore, the fairytale transformation has precedent in superstition and history. Historian Louis Martin notes, “it has long been believed that both demons and sorcerers could transform themselves into the shapes of animals,” exemplified by the 1566 trial of Elizabeth Francis of Chelmsford for making a pact with a familiar for ‘metamorphic prowess’ (Martin 2016, 49). With that said, when a witch transforms into a black dog, she is in no way summoning the Black Dog or any of its variants. The Black Dog, throughout hundreds of examples outlined by both Rudkin and Norman, always acts independently and of its own accord, and much like the triumvirate of time, manipulated by one thing: special boundaries.

Rudkin was the first folklorist to note that most Black Dogs are found on or near parish boundaries (Rudkin 1938, 127 & 129) but do not cross them (Rudkin 1938, 130). Others associate the phantasm with county borders. For example, Brown notes, about the Rudkin study, that

on the Essex-Surrey border, the dog crosses from Middleton to Boxford at Sudbury. On the Norfolk-Suffolk boundary there is a group of dogs, based on the valley of the River Waveney, comparable, perhaps, to the Trent-Tributary settlements in Lincolnshire. The Dog of Bungay is very near the same border, and is remembered on both sides. It does not seem at all certain that the dog is connected with county delimitations. At Uplyme in Devon, the Black Dog used to patrol the Dorset boundary along Dog Lane, behind the Black Dog Inn. In North Devon, Mrs. Carbonnel believes that Black Dogs are intimately associated with certain parish boundaries—Bow, Down St. Mary, and up to Torrington, Frithelstock, etc. (Brown 1958, 183)

Borders act as symbolic chains and fetters, and many of the Dogs reported adhere to haunting specific areas, which may be due to the Black Dog being “a deity of his own right…a phantasmagoria of rural England…and race-memory of the pagan gods” (Witcutt 1942, 167). These pagan connections are not far off from Rudkin’s research that “suggested that the dog-tribe which found itself so much at home in Lincolnshire may not have been welcome in the surrounding areas, which might well account for the supposed ‘death, disaster, and ill-luck’ that parts of East Anglia associate with the dog” (Brown 1958, 179). The Black Death, a paradigm-shifting disease that ravaged Western Europe in the 14th century, also lends “itself naturally to the canine death imagery of the hellhound, blended with that of the werewolf and cynantrophy (White 1991, 68). Packs of hungry dogs often accompanied the piles of corpses that overflowed cemeteries and churchyards, giving folklore fertile ground to borrow and mold from history. For example, in “Messina, where the plague first appeared, ‘demons in the shape of dogs’ moved among men. ‘A black dog with sword drawn in his paws appeared among [the people], gnashing his teeth and rushing upon them and breaking all of the silver vessels and lamps and candlesticks on the altar and casting them” around (White 1991, 68). Consecrated parish grounds, and by extension county borders, which often align themselves along flowing waterways (a folklore staple), keep Dogs within their domain.

Domesticated animals sense the creature’s presence. Brown notes that horses and dogs are terrified when they see the Black Dog. At Willoughton, Lincolnshire, a little dog was petrified by a ghost dog which, to the human being present, was not seen but felt. A case from France describes a series of Black Dog visitations in a house, culminating in two police dogs being set at it when it was invisible to humans; one dog was cowed, the other died from the encounter. (Brown 1958, 187)

Meanwhile, Rudkin recalls a story from the 31st of October, 1933, when Mr. M (who chose to stay anonymous) was walking his dog, which uncharacteristically began barking and growling at something in the hedges before backing off and exemplifying fearfulness. When Mr. M went to check the hedge, the man’s faithful companion pulled with such might that Mr. M let go of the leash and the dog ran home as fast as it could. The fence gate near the incident opened, and Mr. M attempted to shut it but “was forced on to the gate post by something pushing on his shoulders from the front. Finally, he got the gate shut and went in the house, when he told his wife that it was just the sensation of a large dog, as big as an Alsatian, with its front paws on his shoulders having pushed him back on to the gate post” (Rudkin 1938, 123).

The polymorphic nature of the Black Dog is easily explained by local variants on shared myths, legends, historical events, and, of course, the cultural diversity of the population. Mark Norman, like his predecessors, points out that the United Kingdom has the widest diversity of Black Dogs, therefore, it acts as the best case study of its polymorphism (Norman 2015, 17). The sometimes-headless Barguest is a reoccurring sight in Northern England; Staffordshire and Warwickshire are home to the shaggy Padfoot; the calf-sized Freybug is a Norfolk lore staple; the folk of Yorkshire and Lancashire stay indoors when they hear the screeching of the Skriker (also known as a Trash); meanwhile, the coastlines and countryside of East Anglia are the stalking grounds of the large-eyed Black Shuck.

Finally, the Black Dog’s color and its association with malevolence, ill fate, and bad luck may stem from the black cat and its heavy association with witchcraft, misfortune, and familiars. The cat and Dog associations are rather superficial; however, Barbara Hannah makes an interesting point when she notes that “Egyptian gods melt into each other and reappear confusingly, amazingly like the way our own figures of the unconscious behave” (Hannah 2006, 26). Perhaps the same is true here, as Anubis’ relations to other dogs appear and disappear throughout the rest of this article. The Black Dog often exemplifies traits of superficial malevolence—such as its appearance—but acts like a stereotypical guide, protector, or harbinger of the future.

On Lesser Progenitors: Argos, Anubis, and Aesop’s Dogs

Michael Fox, the former vice-president of the Humane Society of the United States, points out that “the nature of the dog is such that it would not be an overstatement to say that the dog helped civilize the human species” (Hausman 1998, 3). While it is widely known that a dog is a Man’s best friend, the lesser-known adage states that dogs are a gift from the gods, or as author Ferdinand Mery notes, “In the beginning, God created Man but seeing him so feeble, He gave him a dog” (Hausman 1998, 5). This sentiment echoes throughout much of Western mythology, going as far back as Ulysses’ faithful companion, Argos, who, after twenty years of his master’s absence, recognized him joyfully before passing away. From Homer,

The dog, with ticks (unlook’d to) overgrown.

But by this dog no sooner seen but known

Was wise Ulysses; who new enter’d there,

Up with his dog’s laid ears, and, coming near,

Up he himself rose, fawn’d, and wagg’d his stern,

Couch’d close his ears, and lay so; nor discern

Could ever more his dear-lov’d lord again.

Ulysses saw it, nor had power t’ abstain

From shedding tears.

(Homer, Odyssey, XVII. 305-313)

The theme of choice, a Black Dog staple, is exemplified in these lines, for both Ulysses and Argos recognize each other, and yet to keep the hero’s mission secret, they do not go to one another, instead of reveling in their reunion from afar. The symbolism that Homer lays upon the dog’s shoulders is that of the difficulty of choice and fear of failure. The tics upon its body are symbolic of time, both past and present problems and pains they caused that suck on what remains of the future. The passage of time is central in The Odyssey, and Argos’ passing upon seeing his master, represents the perseverance and patience associated with reaching one’s goal. Argus, in this sense, is loyalty, be it to another person, task, or, as I discuss later, duty and eventual destiny. Argos is an embodiment of the point in time when contentment enters the soul, the moment before death. However, in the context of cultural chaos—from the Greek khaos politistikós (χάος πολιτιστικός), translated as ‘civilizational chaos’—which I define as a complete or partial malaise or breakdown of ideas, customs, traditions, and social behaviors in a society which, after experiencing a folk, political or civilizational paradigm shift, recedes into an intellectual or creative primordial void, the death of Argos is that paradigm shift. His death is the precursory omen of the incoming violence and wrath that Odysseus will volley upon Penelope’s suitors. The Black Dog’s constant fading in and out of reality and sight is a reminder of that ever-shifting border between order and chaos, the explainable and the unknown, the things-as-they-are and the ever-present sword of Damocles hanging just out of sight.

Illustration 2. Ulysses Disguised as a Beggar, Recognized by His Dog, Argus. Etching by Theodor van Hulden, c. 1630. Source: www.philamuseum.org

Argos’ role is vital in understanding Ulysses’ crossing the border from the supernatural into that of the familiar, and the diplomatic to the violent. While suiters overrun Ulysses’ household, the atmosphere of home is familiar. Argos signifies the milestone of what Joseph Campbell calls the crossing of the return threshold. The Black Dog in its very essence is that threshold: an always moving milestone pursuing the hero, in other words, destiny: a theme prominent in many of Aesop’s Fables, such as the Dog and the Oyster or The Hounds in Couples, in which the dog plays a role of an unaware mentor. For just as much as Argos acts as a symbol of Ulysses’ return, he is also a Cambellian helper: he does not betray his master’s return to Ithaca. He gives him the advantage of surprise against Penelope’s suitors, much like the Black Dog’s signaling of a nearing of anguish and death, not as horrors to be feared, but as eventualities that have to be faced as mortals.

In folklore, dogs are often presented as otherworldly, related to the gods and protectors of wild places such as abandoned ruins and deep woods, yet, primarily, they are assessors of justice, as in Aesop’s The Ass, the Dog and the Wolf. The fable’s theme of choice teaches that “favors beget favors.” So, when the famished dog asks the ass to “stoop down” so that it may feed itself, it provides the donkey with a choice, to which he turns a deaf ear. Thus, when the wolf—a symbol of wildness and knowledge—comes and begins devouring the ass, the dog replies with the same line the ass used, “Wait till our master wakes, he will come to help you without fail” (Aesop 2013, 66-67). The simple act of negligence on the donkey’s part results in swift judgment from both facades of the canine, the civilized dog, and the wild wolf: Cerberus and Fenrir. The act also hints at the Jungian shadow: the duality of Man; the duality of the Black Dog: a domesticated nightmare. The key theme is the negligence of choice. The fable’s dog and the Black Dog act as heralds of choice and, like Argos, by their inaction force the hero to face the consequences of past actions or future inactions via anxiety.

Deities often take on the form of dogs to do battle or pursue their enemies, as in the tale of the Welsh adventurer Gwion Bach. After Gwion accidentally tastes three drops of inspiration from a cauldron of the goddess of poetry and letters, Caridwen, he flees, transforming into a hare, while the goddess gives chase in the guise of a greyhound (Campbell 2008, 172-73). The simple transformation of the otherworldly (the goddess) into the every day (the dog) exemplifies the power that canines have on the human imagination, providing Man with an infinite scope of associations linked with dogs. Moreover, the dog’s link with the celestial signifies its understanding of things that are beyond Man’s comprehension of, for example, the divine, or as sociologist Gerald Hausman puts it, a “dog has a close relationship with God, while man is just begging to know him” (Hausman 1998, 6).

Furthermore, dogs symbolize guidance and act as guardians of the boundary between reality and fantasy, be it heavenly or hellish, as is the case with the Egyptian deity, Anubis. “The dog that swallows millions” (Tyldesley 2011, 110) is a progenitor guardian of shadows at the border and acts as a vital clue to the Black Dog’s symbolism. Natalia Klimczak, an Egyptian Mythology scholar, notes that to “date, archaeologists have not unearthed any monumental temple dedicated to this god. His ‘temples’ are tombs and cemeteries” (Klimczak 2016, 1). Much like the Black Dog’s haunts—churchyards and crossroads—Anubis’ mysticism lies in places associated with fear and the premise they espouse on our imagination that is associated with time. As Lyn Green from the Marshall Cavendish Reference puts it, Anubis “was originally the most important deity linked to funerals and death. Over time, however, this role was taken over by the god Osiris, and Anubis became associated with preserving dead bodies and guiding the dead in the underworld” (Green 2012, 1); a trait similar to that of the Black Dog who acts as a shepherd into the afterlife: a chilling helper, not much different from Argos. Thus, the subtlety of Anubis’ metamorphosis from the god of death to the guide of the dead is akin to Black Dog’s duality as an omen of doom and a benevolent guide, as expressed by Rudkin. This duality as a psychopomp is also present in the Hindu god Yama and his dogs.

Similarly, Jungian psychology sees psychopomps as mediators between the conscious and unconscious—the real and the fantastic—a point discussed below. Barbara Hanna, a Jungian analyst, notes a rather gripping dog-as-guide tale of the Samoyeds of Siberia, who “usually gave their god Ngaa (death) the form of a wolf. When someone was very ill,” the villagers would send for a shaman who would place “an image of the wolf at the side of the tent and then sacrifice” the sick man’s dog. Then the shaman would kill “another dog and as this one” died, the healer would pray to “Ngaa to accept the sacrifice in place of the life of the sick man.” If Ngaa was unsatisfied, then another dog was killed on the grave of the deceased, only for it to be hung with its tail hangs down towards the grave. The idea being that when resurrection occurred, the soul would safely enter the land of the dead under the guidance of the dead dog (Hannah 2006, 75-76).

Poet Susan Lasher expands on the Black Dog’s role as a guide into the afterlife and, through a beautiful metaphor, compares the creature to the night itself,

Strange, bright blackbirds will call to us,

and smooth black stones will clatter.

The black mare and the black colt

will come at a gallop, mane blown black.

Night: lie down beside me, black dog

(Lasher 2000, 271)

It is a very curious comparison, as often night—much like the Black Dog—is associated with fear, darkness, the unknown, and a loss of hope. Lasher subverts this trope to show that the Black Dog is a comforting force, meant to guide the dying into a sublime shadow of the afterlife. I understand that the Black Dog is a metaphor for courage, which one must have when accompanied by fear, to enter death with dignity.

Much like the Dog, Anubis’s “fur was generally black (not the brown associated with real jackals) because black was associated with fertility, and was closely linked to rebirth in the afterlife” (Hill 2016, 1). Jenny Hill, an Egyptology expert from Glasgow University, also notes that “Anubis’ name is from the same root as the word for a royal child, inpu. However, it is also closely related to the word inp, which means ‘to decay." Thus, “[b]y the time of the New Kingdom (c. 1540-c. 1075 BCE), Anubis had become a familiar figure in coffin paintings, where he is depicted bending over the bodies of the dead. In addition to his role in preserving the dead, Anubis helped judge” them (Green 2012, 1), a characteristic often associated with Cerberus. Joyce Tyldesley, Egyptologist at the University of Manchester, points out that Anubis plays a central role in the Court of the Truths—an Egyptian ‘final judgment’ of sort. She notes that “[v]ignettes show Anubis leading the deceased…it is his duty to place the heart [of the judged] in the pan of the scales so that it might be weighed against the feather of Maat, the symbol of truth and justice” (Tyldesley 2011, 163-164). Again, courage toward objective judgement surfaces, along with the motif of the guide dog of potential resurrection.

“The Black Dog of Newgate,” from the book The Discovery of a London Monster called the Black Dog of Newgate by Luke Hitton & Samuel Rowlands, 1638. CC-PD-Mark.

The Black Dog, too, is often referenced as a judge of the living and a road marker that leads them to their destination: the afterlife. An exciting example of this is the Black Dog of Newgate Prison, where after the cannibalization of a scholar accused of sorcery during a famine in the mid-1250s, only the inmates who ate of the scholar’s flesh saw a Black Dog before their death. Unlike Anubis, the Dogs judge when one enters death, not where he goes after. Hill continues, “Tombs in the Valley of the Kings hold one of his epithets, tpy-djuf (he who is on his mountain) refers to him guarding the necropolis and keeping watch from the hill above the Theban [cemetery]” (Hill 2016, 1). Egyptians, a civilization practicing mummification, hoped for eternal life for their bodies, but “between the hungry feral dogs and ill-guarded cemeteries full of shallow pit graves” (Tyldesley 2011, 111) what guarantee did they have for that outcome? Thus, they prayed to the jackal god for physical protection of their future empty husks. “He was also given the epithet khentyamentiu (foremost of the westerners i.e., the dead) because he guarded the entrance to the Underworld” (Hill 2016, 1), an important fact to note when relating it to the Dogs of Yama and Cerberus—both their relationships to Anubis are discussed below in their respective sections.

Additionally, Tyldesley notes that Khentyamentiu was the name of the “original canine god of the Abydos cemetery and the patron god of the Old Kingdom” (Tyldesley 2011, 110), whose name was monikered then usurped by Osiris. Many Black Dogs are guides into the afterlife and continue the work of their mythological predecessors, especially Anubis. Furthermore, the Egyptians believed “that the jackal sought the company of the dead and so gradually promoted it to the rank of a god in the form of Anubis” (Norman 2015, 129). This is quite a promotion: from a carrion-eater to a god, and as noted above, must have happened due to the Egyptian’s fears of losing their mummified remains to feral dogs and theft. The wild dog becoming domesticated via deification brings it one step closer to the intergradation into the human experience. It also sees the creature on the sidelines and ushers it into the living room, where it can be understood, and its knowledge is taken and infused with our own. Such was the role of Anubis and the Aesopian dogs, unlike that of the human-wolf hybrid, the werewolf.

The Werewolf and the Fear of Hidden Knowledge

It is redundant to mention what the werewolf is—a man given the power (willingly or not) to be one with the uncanny—but it is important to note that in dream association, the werewolf is symbolic of “seeing a whole new side to someone” and “wild sexual activity” (“Dream Symbols…” 2016, 1), aspects related to duality. Pagan rituals often shackled wild nature and tamed Man. The werewolf is a personification of these motifs: the wild wolf hidden in the guise of a domesticated dog. While the symbolism is quite clear, the secondary undertone is that of the dog taking refuge in the wildness of the wolf. Nature is made whole in the form of the humanoid beast. This duality has a direct link to the Sun and Moon, to the hidden parts of ourselves emerging under the veil of distorted sunlight. The Sun and Moon are significant aspects of Cerberus and are discussed in finer detail further down in the article.

Some of the first accounts of werewolves come from Greek mythology, and their ties to duality play an imperative aspect in defining the Black Dog. Plato recounts a story in his Republic (Book VIII) in which Pausanias states that atop Mount Lycaeus stood an altar to the Wolf God, Zeus Lycaus, where once “a year a mysterious sacrifice was offered at the altar, in the course of which a man was believed to be changed into a wolf” (Frazer 1890, 169). During the ceremony, the bowels of the sacrificed were mixed with that of an animal, and “the man who unwittingly ate the human bowel was changed into a wolf” (Frazer 1890, 169). There is another account of this tale, where “lots were cast among the members of a particular family, and he upon whom the lot fell was” to become the werewolf. The chosen would strip naked, be led along to a tarn, and after “swimming across it, went away into desert places” where he would be “changed into a wolf and herded with wolves for nine years” (Frazer 1890, 169). If, during this nine-year period, the man tasted human blood, “he had to remain a wolf forever. But if during the nine years he abstained from preying on men, then, when the tenth year came round, he recovered his human shape” (Frazer 1890, 169). Pausanias’ tale is essential in outlining several concepts already discussed: divine association of dog/wolf with the gods, choice, duality, and the negligence to take responsibility for one’s choices.

An interesting symbolic duality of meaning comes in the form of the word warg, or wolf, which “denotes an outlaw or the state of outlawry,” thus referring “to those who have committed crimes that are either unforgivable or unredeemable”—such as cannibalism for example—“and who are cast out from their communities and doomed to wander until they die,” oftentimes in the woods (Stone 1994, 1). Unlike the Greek lycanthrope, the Germanic warg metaphorically becomes “a wolf in the eyes of his fellows…by being outlawed, for murder or oath-breaking; or he can be ou[t]lawed for what he already is, a warg, a worrier of corpses” (Stone 1994, 1). In this sense, the domesticated reverts back to the wild and acts a back-engineered duality in the same sense that Fenrir became wilder as more imprisoned he became by lighter and more ‘civilized’ forms of bondage, as discussed below.

The hidden duality of the wild and domesticated creature is a direct metaphor for the Jungian shadow. However, before exploring the shadow, a quick side note on Joseph Campbell’s monomyth, also known as the hero’s journey. The monomyth a standard template in narrative construction that involves a set of events that a hero experiences during his adventure that end in a climactic victory over an enemy—external, natural, internal, imagined—and acts as a preamble to the hero’s transformation from the state of ignorance to a state of knowing. Campbell’s metaphor of the hero’s journey is both a physical and imaginative trek best noted as “…Aladdin caves. There not only jewels but also dangerous jinn abide: the inconvenient and resisted psychological powers that we have not thought or dared to intergrade into our lives” (Campbell 2008, 5). In other words, the tradition of the Black Dog has its origins not only in the mythology of the journey but also in the collective psychology of humanity, in their deeper seeded, and often, hidden granules of, what Sigmund Freud called, structural models of the psyche: id, ego, and super-ego. In that respect, both the Black Dog and the structural models have a dualistic role for either good or evil. Freud notes in Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego that

when individuals come together in a group all their individual inhibitions fall away and all the cruel, brutal and destructive instincts, which lie dormant in individuals as relics of a primitive epoch, are stirred up to find free gratification. But under the influence of suggestion groups are also capable of high achievement in the shape of abnegation, unselfishness, and devotion to an ideal. (Freud 1959, 15)

Additionally, when discussing Freud’s The Ego and the Id, philosopher İlham Dilman notes that the “ego stands for reason and circumspection.’ It ‘represents what we call reason and sanity, in contrast to the id which contains the passions.’ It can face the demands made on it by the id, the super-ego, and the environment, from a position of strength or one of weakness” (Dilman 1984, 195-96). Pausanias’ werewolf is a metaphorical and mythological embodiment of the structures of the psyche: the ravenous wolf being the id, the human desires inside being the ego, and the domesticated dog that mediates between the two is the super-ego. These structures have been mythologically synthesized into the Black Dog, who acts as a super-ego that must contain the id and ego: it is a manifestation of the shadow, both a horror and a guide to both the individual and the group. In other words, the Black Dog derives the concept of the shadow, a Jungian idea that an unconscious part of the psyche does not identify with the human but with the other, the dark side of being, from the werewolf.

The werewolf in its very essence “is compelling evidence that some archetypal elements of the shadow are not simply split-off personal experiences, but represent a common human experience that the religious traditions associated with an archetypal adversity, whether it be Satan or Iblis or Ahriman” (Moore 2003, 37). The werewolf is a personified rebellion against the domesticated self, but it is also the toying with the remaining feral. Humanity scapegoats this savagery onto the ghostly and uncanny—in all its definitions, for as Freud notes, it is “beyond doubt that the word is not always used clearly definable sense, and so it commonly merges with what arouses fear in general” (Freud 2003, 123). Meanwhile, Jung notes that to “all that is in any way out of the ordinary and that therefore disturbs, frightens or astonished [Man], he ascribes what we should call a supernatural origin. For him…these things are not supernatural; on the contrary, they belong to his world of experience” (Jung 1933, 127). Pausanias tells of the nine-year curse of the wolf becoming one of eternity for the cursed; it may not be a phase but an end in itself. Besides being the shadow, the werewolf also hints at being a fragment of the Freudian death drive, Thanatos. While discussing Eros vs. Thanatos, Professor Moshe Halevi Spero mentions that this “death-instinct [Thanatos] expresses an innate tendency toward catabolism, i.e., any organism’s fatal evolution toward stagnant inertia. (At certain levels, Freud makes little distinction between man and animal.)

Moreover, he considered that is the earliest state of an organism was an inanimate one, this regulatory principle of the aggression drive called for a return to the state of death” (Spero 1975, 101). The Black Dog is soaked in this motif: Man’s psychological need for release from life, for the end, is fueled by torpor and ennui over time, but which in its still-state cannot go through with a psychological Ragnarok and chooses to adhere to following the harbinger of this end, the domesticated dog. W.M.S. and Clair Russel point to an interesting biological distinction between domesticated dogs and wolves: the tail. A wolf’s tail is upturned, while a dog’s is sickle-shaped or curled; one points skyward, the other—the domesticated one—more earthbound (Russel 1978, 161). Symbolically, earth-awareness—as in the case of Cerberus, discussed below—overlaps with the knowledge of inevitable death and burial. The werewolf is, therefore, the wish to escape the knowledge that there is an end. Animals are not aware of death-in-the-future as a concept, thus the emergence of Pausanias’ werewolf: an oblivious shadow born from death-awareness.

“Werewolf or the Cannibal.” Woodcut by Lucas Cranach the Elder, ca. 1512. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. CC0.

The hidden knowledge that the human pushes to the back of their mind is the inevitability of death, and the “crime of education consists in the child not being prepared for the rule of the eternal battle between the two heavenly powers, that is, between Eros and Thanatos (see, Freud 1972; Haase 1999, 129)—a battle that determines human life as ruled by violence and war on many fronts:” against the forces of nature (Haase 1999, 82), all other human beings (Haase 1999, 102), and “against itself, insofar as the ego is engaged in constant war with an id that tries to win back territory lost to the ego, and with an over ego, constituted by the invasion of the other into the sphere of the ego” (Haase 1999, 38). This battle between past and future occurs in the present (we tell ourselves this via myths), and the Black Dog is the singularity of those battle, of those hidden fears and a deep-rooted knowledge that we are mortal. The werewolf and the Black Dog are connected by another thread: the Freudian uncanny, which “does not arise from lurking monsters or witches or other fantasy threats from fairy tale, but is primarily an effect of profound disturbance sparked by something familiar, that is homely,” such as the symbol of the dog, “which awakens a repressed memory of forbidden desire or trauma: ‘something which ought to have remained hidden but has come to light” (Warner 2014, 120), like the wild form of the Pausanias’ wolf that emerges from Man.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s novella, Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, is a great metaphorical and literary example of the animalistic ‘wolf’ making itself manifest as uncanny behavior. The character-as-threshold that is the Black Dog and Henry Jekyll is best expressed by Dr. Jekyll’s musing on his duality. He states, “man is not truly one, but truly two. I say two, because the state of my own knowledge does not pass beyond that point…I hazard the guess that man will be ultimately known for a mere polity of multifarious, incongruous and independent denizens” (Stevenson 2002, 67). This multiplicity of human ‘roles’ would later be expanded by Jung with his evolution of the term archetype. I wonder if the Black Dog and its polymorphic uncanniness was a foreshadowing of that evolution?

Additionally, the German Doppelgänger, or double, “in all its nuances and manifestations—that is to say, the appearance of persons who have to be regarded as identical because they look alike” (Freud 2003, 141), added to the confusion between the doubling of form but not of action. As stated before, the Black Dog is nothing but a dog from afar, but once the distance between the viewer’s eye and the beast shortens, fear and dread are evoked. The creature begins as “the homely and the domestic,” but then “there is a further development towards the notion of something removed from the eyes of strangers, hidden, secret” (Freud 2003, 133), something not quite right. Hence the Black Dog, like the uncanny itself, “is that species of frightening that goes back to what was once well known and had long been familiar” (Freud 2003, 124). These comparisons lead “us back to the old animalistic view of the universe, a view characterized by the idea that the world was peopled with human spirits…the omnipotence of thoughts and the technique of magic that relied on it, by the attribution of carefully graded magical powers (mana) to alien persons and things” (Freud 2003, 147). In this sense, the uncanniness of the Black Dog relates to the witchcraft and mysticism discussed earlier, and alludes to the unfamiliar backdrop of Cerberus and the Dogs of Yama, discussed ahead.

The psychological triumvirate—id, ego, and super-ego—is a psychological representation of the three human fears: past, present, and future, which are represented in the form of the myth of the three heads of Cerberus, who is simplified further into the Black Dog. The uncanny three-headed dog becomes one-headed, yet what it represents continues to stay the same, and streamlining occurs. The werewolf may be the human want for forgetting the unavoidable outcome of life, but “Cerberus seems an ideal ego representation. He is a perfect antiauthoritarian especially within the religious sense being a hybrid born of a half-woman and serpent, and a fire-eating giant; the latter, his father, feared by the Olympian gods, and his mother representing two less favored creatures of Christianity” (Mystica 2017, 1), and acts at the perfect prototype for the Black Dog.

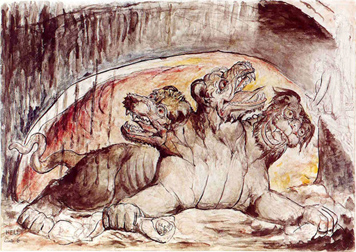

As an aside, Cerberus himself, while rarely referenced by the color of his coat, is noted in various translations of Seneca’s Hercules Furens as “dusky” (by Frank Justus Miller) or “black” (by John G. Fitch) when led through the streets of Greece by Herakles (Seneca, Hercules Furens, 55-59). Furthermore, Cerberus is depicted as having a black body and one black head on a vase dated 530 BC, housed at the Louvre Museum, Herakles and Kerberos (item: Louvre E 701).

Cerberus and Black Dog as a Representation of Jung’s Shadow

According to Homer, the underworld, Cerberus’ home, “is vague, a shadow place inhabited by shadows. Nothing is real there. The ghosts’ existence…is like a miserable dream” (Hamilton 2011, 39). The creature’s home hints at its horrific and eerie existence while simultaneously suggesting the ever-changing, almost ungraspable, and murky duality of its symbolism. The shadow world, be it in fantasy or as a philosophically ambiguous location, plays on human emotions and doubts, and just like the Black Dog, who appears in the blanketing darkness of the night, it relies on human imagination and perception of the unknown to frighten and challenge. In this context, night, or the shadow—especially during the Witching Hour—is a gate, a curtain, between the concrete reality of the bright daytime and the infinitely abstract abyss of the moonlit world. The veil of night is a metaphorical doorway that gives birth to Man’s infinite imagination and guards the unreal against the real in the form of the infernal sentinel, a mythological shadow onto which we as moderns can project our evils: Cerberus.

Much like the werewolf, Cerberus is a mythological variant of Jung’s shadow: a monstrous manifestation of the id, ego, and super-ego as one, but now, when modern science expelled “gods and demons…from nature” they and Cerberus “have found a new, though less spacious, abode in the human psyche” (Avens 1977, 196). To those unfamiliar, a quick recap of Jungian nomenclature: the Jungian shadow is that ever-present but unknowable part of our psyche that often lashes out against self and the world, but which hides within it potential for overcoming; Jungian archetypes are the ancient and universal symbols that materialize themselves in often classical characters and motifs, such as the trickster or the end of times; these archetypes stem from the Jungian collective unconscious which is a shared omnipresent structure of instincts, systems, and ideas—in other words, it is the Platonic realm of forms. Circling back, what was once allegory is now psychology, and the symbolism is no longer strictly mythological but also psychological and oppressed by jargon. Cerberus acts as a compartmentalization of the complex, the wild, and domesticated nature of humanity, which yearns for ignorance in the haze of darkness, all the while forgetting its ever-galloping end. However, “modern civilization provides inadequate opportunities for the [psychological] shadow archetype to become individuated because in childhood, our animal instincts are usually punished by parents. This leads to repression: the shadow returns to the unconscious layer of personality, where it remains in a primitive, undifferentiated state” (Avens 1977, 199). The oral storytelling of the past provided an outlet for these shadows and gave them form via imagination. The fairytale, or ‘the great mother of the novel,’ sprang forth as a symbolic torch to tame the shadow, and as Jung would argue, “that what has been on everyone’s lips for millennia, though repeated endlessly, still comes nearest the ultimate human truth” (Jung 2009, 224). Expression of the shadow was important, unlike today, where social and news media mask those specters, so when the shadow “occasionally breaks through the barrier of repression, [it] manifests itself in pathological ways, for example, in the sadism of modern warfare and the crude obscenities of pornography” (Avens 1977, 199). Cerberus was a guardian of the unconscious and a mediator of the real and the unreal fantastic. In that sense, Cerberus “through many [symbolic] transformations and even a long process of more or less conscious development,” became a collective image “accepted by civilized societies” (Jung 1964, 83) as threshold keeper. The three-headed mythological shadow functioned as a filter for the fact that most human beings are far more malicious and self-absorbed “than they like to appear either to themselves or to others. The [psychological] shadow is the sum of these unpleasant qualities together with insufficiently developed functions; it represents…the contents of the personal unconscious…things we want most to deny,” or repress during our lifetime (Avens 1977, 200). Psychology has a mythological scapegoat.

A similar motif is present in Norse mythology where Odin’s war wolves, Freki and Geri, “represent the more sinister side of Odin as the god of the dead, as they are…animals that eat the corpses of battle” (Enoch 2004, 33). They are the mythological shadows that consume the psychological shadows that hope to make themselves present in one’s life. The mythological shadow in the form of the wolf/dog exists in an unconscious and timeless territory, which both Freud and Jung acknowledge as containing all of being, “even the so-called conscious mind is not separated from the unconscious in any absolute way and contains opposites existing side by side” (Golden 1985, 204), which suggest that Cerberus is timeless, the guardian of the boundary between tangible reality as expressed in action and the intangible, unconcise world within, expressed in thought and fantasy. Thus, what Jung “means by acceptance of the shadow (or integration of evil) is not an approval of “sin" or compromise with wickedness, but new freedom to act out of one's inborn wholeness” (Avens 1977, 204), to make the real and the fantastic merge in us, a reverse werewolf where the potential in the unconscious can manifest. However, Jung also reminds us that “consciousness is a very recent acquisition of nature, and it is still in an ‘experimental’ state. It is frail, menaced by specific injuries, and easily injured” (Jung 1964, 6). Thus, we must be ready to struggle even when guided by the Dog of Thresholds, because even though he may lead us along, the steps and actions taken along the path must be willed by the traveler, much in the same way as Dante in The Divine Comedy.

Much like the Black Dog, “it is important to realize that the shadow is not necessarily nefarious or wholly bad. It also displays good qualities-normal instincts, creative impulses, and realistic insights. The shadow is "negative" only when seen from the viewpoint of consciousness” (Avens 1977, 201). This means that when the psychological shadow overtakes the scapegoat of the mythological shadow, and the harbinger of the future is not a mythical self but an inert self, then we dispose of Argos, our silent guide, replacing him with nothing. The Black Dog that has been guiding us along to Thanatos is ignored, and we descend into an abyss of our own making: depression, addiction, unfulfillment, or self-harm. Thus, a strong will is necessary during descent (be it Herakles fetching Cerberus, or Tyr placing his hand in the maw of the Monster of the Ván) to be able to climb out.

Cerberus and the Dogs of Yama: Duality of Gatekeeping

Cerberus’ relationship to duality is vital to the formulation of the Black Dog, so let us unearth Echidna-spawn’s dichotomy by exploring its origins and links to the Dogs of Yama. Professor Max Müller noted in the Preface to Contributions to the Science of Mythology (p. xvi) that Kerberos (a variant on Cerberus’ name) is a stem from Vedic Çarvara, “from which is derived Çarvari” or night (Bloomfield 1904, 539). The Vedas, ancient Indian holy texts, declare that the “sun and moon are the Cerberi” (Bloomfield 1904, 540). Thus, our first hint at the three-headed dog’s duality.

Cerberus was the offspring of the Olympian terror Typhon, “a huge fire breathing dragon said to have glowing red eyes, a hundred heads, and a hundred wings,” and the mother of all monsters Echidna, “a half-woman, half-snake creature known as the "mother of all monsters” (Hilliard 2015, 1). According to Hesiod, Cerberus’ parents came from unlike worlds: Typhon from the heavens and Echidna from the deep. Therefore, in “heaven…and not in hell, is the likely breeding spot of the Cerberus myth” (Bloomfield 1904, 540). Serpentine symbolism of cunning and sin—a crucial aspect of Christian mythology—is present in Cerberus’ heritage. From Hesiod to Plato to Virgil and Ovid, serpents are always a key component of the creature, be it “his neck is bristled with serpents” or that his mane is “shaggy with serpents” (Bloomfield 1904, 525). However, the symbolism of the serpent in Greek mythology is that of hidden wisdom (Minoan snake goddess), healing (Staff of Hermes), and rebellion (The Gorgons); concepts associated with the Black Dog concerning it being a threshold guide between the real and fantastic. However, the serpentine association is connected to Egyptian mythology and the concept of eternal recurrence. Marie-Louise von Franz, a Jungian psychologist, notes

Isis swears first in the name of Hermes, which is probably the Greek translation for Thoth, the moon god…then in the name of Anubis, which has not been translated and therefore is recognizable in its Egyptian form, and also in the name of Kerkoros—the howling of Kerkoros, referring to the howling of the dog Kerberos. In the parallel text the name is Kerkouroboros. Ouroboros is the snake which eats its own tail, so it must refer to a doglike demon which has been confused with this snake and is here described as the snake and the guardian of the underworld. So this is a mixture of the figure of Kerberos, therefore ‘Ker’ in the first syllable, with certain guardian figures of the Egyptian underworld, among which we very often find the snake that eats its own tail. (Franz 1980, 69)

Thus, the acts of destruction and creation associated with the Egyptian Ouroboros are also, by accident or intention, part of Cerberus’ heritage. Furthermore, the symbolism of Ouroboros as eternal cyclical renewal fits with the above-mentioned allegorical meaning behind both Argos and Anubis, suggesting to me that the connections of time and recurrence to the mythological dogs may have a lot to do with collective human imagination and pattern creation.

Illustration 5. “Cerberus” from Illustrations to Dante’s ‘Divine Comedy.’ Graphite, ink and watercolor on paper by William Blake, 1824-7. © Tate. CC-BY-NC-ND (Unported 3.0).

Another fundamental association, subtler than that of the serpent, and one of great importance later in our discussion, is earth. Cerberus, who is regarded as ‘flesh-eating,’ is described by numerous commentators of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy and Vergil’s The Aeneid, such as Pietro and Iacopo Alighieri, Bernard Silvester, Benvenuto de Imola, and Boccaccio, as ‘earth eating’ and associate the creature with terra (Savage 1949, 408). Cerberus is both a creature of terra and shadow and until Herakles dragged him out of Tartarus, he was beyond the grasp of Man. Furthermore, Earth, a plane of existence, is, mythologically speaking, the middle ground between the divine (Sun) and the mystical (Moon)—see the symbolism present in Greek (Apollo, Dionysus, and Hecate), Egyptian (Ra, Thoth, and Khons) and Norse (Sunna, Máni, and Odin) gods and their relationship with the divine and mystical of their respective mythologies. Earth and shadow are critical in funeral proceedings: incense smoke flowing from a thurible accompany the buried. During Ancient Greek burials, “the deceased was brought to the cemetery in a procession, the ekphora, which usually took place just before dawn” (Department of Greek and Roman Art 2003, 1) when the moon was still present, and the sun was soon to overtake it—passing from the mystical shade to the otherworldly divine via the earth, or in some cases fire. It is no coincidence that the Black Dog is often sighted in shadow around churchyards. Mark Norman points out that people believed “that the first burial in a churchyard must watch over the other dead and so a dog was sometimes buried instead of a human for this purpose” (Norman 2015, 132), both to watch and to guide.

The duality of the dogs of the Hindu god of death, Yama, is central to Cerberus’ dichotomy. The dogs, symbolizing Light and Darkness, the Sun and the Moon, are mentioned in prayer for long life in the Hindu holy text, the Atharvaveda: “The two dogs of Yama, the dark and the spotted, that guard the road (to heaven), that have been dispatched, shall not (go after) thee!...Remain here, O man, with thy soul entire! Do not follow the two messengers of Yama; come to the abodes of the living” (Bloomfield 1904, 529). The prayers describe the will to live in the light, away from the depths of the earth and shadow-death. The dogs, named Çyama and Çabala, are representations of Night and Day, respectively. Their symbolic messenger is the werewolf.

Çyama, the moon dog, is black, and along with his spotted brother, leads the deceased along the path of the dead into the Netherworld. The Milky Way acting as that path. Yama’s dogs have similar symbolic roles as Anubis or the Black Dog; however, they also act as caretakers and “guard the way [into the afterlife] and look upon men favorably; hence they are ordered by Yama to take charge of the dead and to furnish them such health and prosperity as the shades happen to have use for” (Bloomfield 1904, 533). The dogs of Yama are often compared to Odin’s twin wolves, Geri and Freki, mostly because Freki is noted to be the night hound of violence and because of philologist Maurice Bloomfield’s comparative mythology work. However, unlike the dogs of Yama, Odin’s wolves, are associated with greed and violence, and in that sense, also act as hidden metaphors for Odin himself, a benevolent father with a hunger for the horrid (Ragache 1988, 42). Again, duality presents itself. Enter Egyptian mythology and Anubis once more: Rwti, or the double lion, with a sun disc between its backs “is how the god, or the word Aker, is represented. He is shown as the double lion, or the double dog, or as Yesterday and Tomorrow because in Egyptian mythology, this whole picture represents the moment of the resurrection of the sun god. Yesterday he was dead; tomorrow he will be alive again” (Franz 1980, 70-71). Interestingly enough, when the lions are depicted as “two Anubis’ jackals, two doglike animals…then the inscription below is: ‘These are the openers of the way, the agents of resurrection” (Franz 1980, 72). So once more, an allusion to eternal reoccurrence and the Ouroboros.

Before I continue, Brown mentions a curious sighting of a two-headed Black Dog: “Two Heads. At Kildonan, Sutherland, a treasure hidden in a pool is guarded by a two-headed dog. Cf. Orthrus, the two-headed dog of Geryon (Brown 1958, 180). In Greek mythology, the two-headed Orthrus was the son of Typhon and Echidna’s and Cerberus’ brother and was killed by Herakles. Orthrus, much like his more famous sibling, was a guard dog, in charge of keeping Geryon’s cattle safe, i.e., keeping the household’s wealth and health secure. So, much like Yama’s dogs, he was to “furnish them such health and prosperity… [as they] happen to have use for” (Bloomfield 1904, 533). Thus, it seems that Çyama and Çabala’s caretaking attribute is more in tune with Orthrus and Cerberus than Odin’s wolves.

With all of these mentioned, let us look at Cerberus’ gatekeeping. Edith Hamilton, an American Classicist, points out that “on guard before the gate sits Cerberus, the three-headed, dragon-tailed dog, who permits all spirits to enter, but none to return” (Hamilton 2011, 40). The role of Cerberus—the one who permits and recognizes heroic shades as they enter the imagined and fantastic realm—is symbolic of the narrative framework of the Campbellian hero’s journey, which is a sort of glimpse behind the veil of the solid and dull world we live in, and as the presence that shields the hero from the intangible: his unconscious. Thus, Cerberus stands outside of the gates of the dream-like Netherworld as a wall between the hero and his return to the concrete realm. In other words, the sentinel, by force, wishes the hero to stay as a spirit in the world of fantasy so that he may escape from the difficulties of life. Thus, like the dogs of Yama, the hellhound wishes for the hero to stay in a comfortable daydream. Whether he is aware of this odd benevolence is unclear.

In this context, daydreams are a space for fantasy and imagination to take intangible form before entering reality; they are the space of Gods and act as ambrosia in the Elysian Fields, i.e., a creative spring for writers, artists, musicians. Hence, it adds up that “[a]s the guardian of the gates of hell Cerberus also keeps spirits from entering hell; in this sense, he protects those striving to deify themselves from influences that want to degrade them, make sacrificial lambs of them. Cerberus… [and Orthrus] safe guard the fortitude of the ancient gods” (Mystica 2017, 1). This is a popular theme in fairytale tradition and seen in Peter Pan, Wizard of Oz, or The Earthsea Cycle.

Therefore, it is interesting to see this theme in an allegorical and comical story by Georges Agadjanian, In the Footsteps of Cerberus, about the daydream of a house dog named Fido, who wishes to be Cerberus. The secondary theme is the pressure and responsibility of being a guardian between the reality and fantasy of life. I think the themes in the Fido story are significant to this analysis, hence the following summary: After Fido dies, he comes before God and asks to become the next Cerberus, but since Fido was a good dog, God wishes for him to stay in heaven. Nevertheless, Fido is determined, so God sends him away to deliberate the request and, in a dream, shows Fido what Cerberus is surrounded by in Hades: fire and brimstone and death. Fido asks God why this is so, and He tells him that His Hell is incomplete, much like Man. Man suffers, and Hell reflects that suffering. Once Man comes to gain suffering-born wisdom, he becomes complete and gains the insight to emerge from the darkness of Hell and into the light of Heaven. Fido wakes up and realizes what God meant by the dream: Earth is Hell and that there is not one Cerberus but many:

“Therefore, there is no Hell except on Earth—where you have come from. And now answer me: do you still want to be a Cerberus?"

"What dost Thou mean?" asked Fido, who could hardly follow.

"I'll have you reborn as a man and you shall be caretaker of a building. Or, if you are ambitious, you could be a banker, the prosperous, incorruptible guardian of enormous funds. Or again, a politician, avowed defender of a certain social system…”

"Oh no!" howled Fido. "I'd rather stay a dog."

"Your choice is judicious," said the Almighty, "and you really deserve to be kept in Heaven"

(Agadjanian 1952, 143).

The daydream is often greater than the reality needed to house it, thus the need for the guard of the gate through which the ideal can become tangible.

The importance of the gate guard of daydreams is best exemplified during times of cultural chaos. When cultural paradigms shift and the threshold of fantasy is embraced as reality, psychosis, and moral panic ensue. Past guidance is interpreted as suppressive of future progress. The individual within this chaos retreat into a dark variant of fantasy because reality “is too strong for him. He becomes a madman, who for the most part finds no one to help him in carrying through his delusion” but who manically wishes to correct “some aspect of the world which is unbearable to him by the construction of a wish and introduces this delusion into reality” (Freud 2010, 51). During times of cultural chaos, the dog’s symbolism takes on the duality of a messenger of and protector from incoming danger. Scholar Richard Cavendish notes that dogs “are uncanny because they howl in the dark outside when all right-minded creatures are asleep” (Cavendish 1975, 62), but they do so to warn and scare away. In this sense, Cerberus had a singular function of preventing the living from entering the underworld and the dead from leaving it (Cavendish 1975, 62), or to keep the living in reality while keeping the madness-inducing specters of the past from shaping the future. However, the guardian dogs sometimes fail to keep the mighty dead at bay, and when that occurs, a—usually violent—cultural rebirth transpires.

The powerful dead, or “saviors” as Osiris, Tammuz, Orpheus, Balder or Herakles are often of divine or semi-divine birth, flourish, are killed, and are reborn (Jung 1964, 99), act as the metaphorical rejuvenations after the completion of the cycle of cultural chaos. In these instances, a peaceful cultural rebirth transpired, but as noted above, that is usually not the case; the paradigm shift is violent. It begins with the increase of society-wide anxiety, which “describes a particular state of expecting the danger or preparing for it, even though it may be an unknown one” (Freud 1961, 11). When the supporters of either side of the threshold—fantasy and reality—have nothing to offer to one another, “except narcissistic satisfaction of being able to think oneself better than others” (Freud 2005, 146), then the guardian dogs turn on both. In these cases, folklore provides us with the violent packs of spectral dogs, be they the Wild Hunt, the hellhounds of Welsh lore, or the ‘wisht hounds of Dartmoor.’ Here the “terror of them lies largely in the reversal of normal roles. The hounds…hunt man to his own death. They…are linked with the image of the devouring Death, the eater of men” (Cavendish 1975, 63). Through this violence, they leave humanity to “stands upon a peak, or at the very edge of the world, the abyss of the future before him, above him the heavens, and below him the whole of mankind with a history that disappears into primeval mists” (Jung 1933, 196). Through this violence, there arrives an epoch of mass cultural forgetfulness whose past achievements remain only as flickering wisps in the collective unconscious. The threshold guardians, tasked with being watchful of the gate, became false and attacked the living, so it is “perhaps not surprising [that do to their duplicity] no dogs are allowed into the heavenly city, New Jerusalem, in the book of Revelations” (Cavendish 1975, 63). Thus, through Cerberus’ role as a gatekeeper, we can see, too, the Black Dog’s numerous allegiances: the real, the fantasy, and the self, all connected by the thread of laboring toward cultural equilibrium.

Cerberus as Labor and Symbolism

The metaphor of the twelfth labor of Herakles—arguably the most difficult of the bunch—exemplifies the strain of the journey into one’s subconscious imagination. The wounds that Cerberus inflicts on Herakles are reminiscent of the disillusionment experienced by those who return to reality after being engrossed in a good book, film, or a session of focused creation, or as Carl Jung called it, the madness of the creative spirit, be it inventing, writing or painting. However, to indulge in one’s creative spirit, a strong will of perseverance is needed, which is why Jung believes that “[t]his is why we find self-discipline to have been one of man’s earliest moral attainments” (Jung 1933, 33). The myth goes that Eurystheus, king of Tiryns, orders Herakles to kidnap Cerberus. Optimistic that the task is physically impossible, Eurystheus is gleeful at the prospect of finally coming up with a labor that Herakles will not complete. Three things stand in Herakles’ way: the descent into the underworld, Hades, and Cerberus himself.

Illustration 6. Hercules and Cerberus. Oil on panel by Peter Paul Rubens, 1626-37. Museo del Prado. CC-PD-Mark.

Metaphorically, the labor is symbolic of entering one’s immeasurable psychology, and Herakles does just that and more by venturing into the psychological beyond the imagination. An aspect of human nature is such that it strives for pleasure, and once Man tastes the sweetness of fantasy, of the ambrosia of imagination, he is reluctant to escape its clutches. This nature is similar to “the actual dog, it simply obeys its inner urges. And to it, every urge is ‘good” (Hannah 2006, 71). Those who struggle to return to reality must turn toward the sentinel at the gates: the superego, a self-policing, self-perpetuating Cerberus whose three heads are symbolic expressions of Man’s body (his physical existence), reason (his rational existence), and imagination (his fantasy/pleasure-driven existence). So, when Eurystheus sent Herakles to kidnap the “unspeakable Cerberus, who eats raw flesh / The bronze-voice hound of Hades, shameless, strong, / with fifty heads” (Hesiod, Theogony, 311-313), he sent him to venture into his imagination and retrieve from it the rational side of passion.

As mentioned before, Cerberus is often described as flesh-eating or a physical manifestation of gluttony. For example, as noted by Bryan Hilliard, “Cerberus appears in Dante's Inferno, guarding the third circle of Hell rather than the entire underworld. This is the circle of gluttony, and Cerberus is used to personify uncontrollable appetite” (Hilliard 2015, 1). The metaphor is clear but is also worth reiteration as it applies to the ominous side of the Black Dog: a person, much like Don Quixote, can become too entrenched in fantasy only to wither away mentally or physically. Through the constant consumption of fantasy via books, philosophies, films. The feeding of one’s wants on the wishes and illusion of another’s perception, the superego can devolve, becoming an id. Thus, the creature’s flesh-eating attribute is one of warning that we should not spend too much time along with the great beast of gluttony as it may itself become hungry for our sanity, as was the case with Friedrich Nietzsche, Nikola Tesla, or Lord Byron. Furthermore, the creature’s serpentine origins—which rear their head again via a note by Henry Riley, a translator of Ovid’s The Metamorphoses, state that,

There was a serpent which haunted the cavern of Taenarus, in Laconia, and ravaged the districts adjacent to that promontory. This cave, being generally considered to be one of the avenues to the kingdom of Pluto, the poets thence derived the notion that the serpent was the guardian of the portals. Pausanias observes, that Homer was the first who said that Cerberus was a dog; though in reality, he was a serpent, whose name in the Greek language signified ‘one that devours flesh.’ (Riley 1899, 274)

In this context, the symbolism of the snake is representative of an umbilical cord between Deep Earth and High Heaven, or relatively grounded reality and lofty fantasy, which alludes to the sub-context of the Dogs of Yama. Cerberus’s original imagery and connotation can be connected to that of the Biblical serpent: creativity, transformation through consumption, and rebellion are all tied to the unknown and the potential of failure.

As mentioned in the story of Fido, individual perception of the role of guardianship may result in the misconception of what the reality of guarding something entails. Both Cerberus and the Black Dog guard the threshold between reality and fantasy, a theme adopted by Hecate, the goddess of entrances and keys to hidden truths, among other things. Brown notes that Roman Diana, the triple goddess of the hunt, crossroads, and underworld, is a “deadly Hecate owning the three-headed Cerberus,” who began his life as a fifty-headed canine (Brown 1958, 190). Brown continues that the “later reduction to three heads matches Hecate, who also had three heads, representing [H]eaven, [E]arth and [H]ell, as well as the ancient tripartite year, of which the dog-head stood for the dog-days of harvest” also known as the Hecateias idus, which took place on August 13th, a festival of Diana during which “Romans specially honoured (sic) their hunting dogs” (Brown 1958, 190). These honors stem from the belief that dogs are creatures of “the threshold, the guardian[s] of doors and portals, and so appropriately associated with the frontier between life and death, and with demons and ghosts which move across the frontier” (Cavendish 1975, 62). The symbolism of the goddesses and their association with dogs flows into a staple of English lore, as “in the vision of Thomas of Ercildoune, near a triple-headed hill above the Monastery of Melrose, where the Queen of Faerie came with three hunting-dogs on a leash to convey him underground” (Brown 1958, 190). The mythological Queens of crossroads and hidden things all had their triple-headed guard dog, which I argue became diluted into that of the Black Dog.

Before returning to Herakles, it is essential to discuss the symbolism of the three heads, which in contemporary psychology is represented as the ego, id, and super ego—bound by the body of time, among a plethora of other meanings. “Commonly the heads have represented (Cerberus' psychic ability to see into) the past, present, and future or birth, life, and death,” the three ages of Man (Mystica 2017, 1). Bloomfield also notes that “the three heads are respectively, infancy, youth, and old age, through which death has entered the circle of the earth” (Bloomfield 1904, 526). Cerberus, as earth or corpse-eater, is Earth itself: the giver of life and the final resting place from which new life, such as the Black Dog, emerge. In a way, the Black Dog is an emissary of the Cerberus. Savage parrots Bloomfield and sees the “three heads as symbolic of the three ages of man, infanita, iuventus, and senectus” (Savage 1949, 407). However, he also suggests that they might refer to the three continents thought of existing during the ancient times and notes that “Dante himself in his De monarchia (2,3,4f) develops in detail the conception of Aeneas’s connections with all three continents both by birth and by marriage alliances” (Savage 1949, 409), creating a subliminal connection between the Hound and “Aeneas, who was guided by Sybil who drugged the dog [Cerberus] with opium and honey” (Rose 2000, 73). It is curious that in this rendition of Cerberus, pleasure overpowers the guardian: opium, honey & music, much like the Freudian trio, is always at a struggle with pleasure itself. The struggle is not a singular event, but one that persists throughout life: infanita, iuventus, and senectus.