Cultural Analysis, Volume 19.2, 2021

The Revival of Finno-Ugric Studies in Soviet Estonian Ethnography: Expeditions to the Veps, 1962–1970

Abstract: Estonian ethnographers (ethnologists) have been interested in Finno-Ugric peoples, linguistically related to the Estonians, since the early 20th century. The Golden Age of Finno-Ugric studies started in the 1960s when Estonian ethnography was already subjected to Soviet ethnography. The preferred destination of Estonian researchers was the isolated and archaic southern Veps area. Old phenomena were disappearing there, and Estonian scholars studying ethnogenesis had to hurry to save what they could for science. Relatively free access to the eastern kindred peoples was their advantage in international Finno-Ugric studies—almost the only way to the world outside the Soviet camp for the Estonian ethnographers. Besides, expeditions to the linguistic relatives got a positive response in Estonian society as they were supporting Estonian identity independent from the Soviet regime.

Keywords: Estonia; ethnography/ethnology; Veps; fieldwork; Finno-Ugric studies; Soviet Union

____________________

Introduction

This article focuses on the revival of Finno-Ugric studies, an essential topic in Estonian ethnography,1 after World War II, specifically in the 1960s. At that time, most expeditions outside of Estonia went to the Veps, although the interest in Finno-Ugric peoples was much broader. This paper aims to place the Finno-Ugric research of the then Estonian ethnographers into a broader context of Estonian cultural history and history of European ethnology in order to analyze aspects of its foundations and influences.

There are several questions I wish to address. Why would Estonian ethnography be concerned with peoples outside Estonia? What were the aims of the research trips to the Finno-Ugric peoples, and how did they relate to other studies of Estonian ethnographers? What were the work methodologies and results? What were the relations between Estonian ethnographers and the peoples they studied? How did these trips affect Estonian society and the peoples researched?

From 1960 to 1970, the material from 20 Finno-Ugric expeditions was placed in the Estonian National Museum (ENM)2. Five of these trips (to the Valdai Karelians, Mokshas, Komi-Permyaks, Khanties, and Komi-Zyrians) could be called brief excursions not immediately followed by more thorough research and the academic results of which remained modest. The nearby Baltic Finnic peoples were the immediate focus, with nine expeditions to the Veps, 4 to the Livs, and 2 to the Votians.

The article takes a closer look at the Estonian ethnographic research undertaken among the Veps from 1962 to 1970. The primary sources are academic and popular texts based on the expedition material, field diaries, and contemporary media coverage in Estonia. Interviews with people who took part in the trips were also analyzed (Evi Tihemets, Lembit Võime, Hugo Puss, Erika Pedak, Heiki Pärdi).

Cultural Background

The focus of the Estonian ethnographers has always been Estonians and Estonia. However, the Estonian language is one of the Finno-Ugric languages. Estonian cultural researchers (folklorists, ethnographers) were interested in other Finno-Ugric peoples ever since these disciplines came into being as branches of the Estonian studies.3 The roots of this interest were intertwined with the national movement that initially swept over Finland in the 19th century and reached Estonia a little later. At the beginning of the 20th century, an awareness of one’s Finno-Ugric roots and linguistic kinship would spread to become a cornerstone of the ethnic identity of both Finns and Estonians. For the latter, language is the central defining feature of their ethnicity, and hence the idea of linguistic kinship is important to them. Some intellectuals extended linguistic kinship to cultural and even biological kinship. The Finno-Ugric peoples’ movement (hõimuliikumine) was born on that ground. In the 1920s and 1930s, many Estonian students, scholars, and even politicians were involved. The closest contacts were kept with Finland and Hungary.

Until the end of the 1940s, the Estonian National Museum was the center of Estonian ethnographic research. The museum housed ethnographic collections, and from the 1920s onward, the teaching of ethnography at the University of Tartu was closely linked. Due to the shortage of local experts, Estonian ethnography in the 1920s had to rely on Finnish scholars, such as the archaeologist Aarne Michael Tallgren and the ethnographer Ilmari Manninen. They were also committed to the Finno-Ugric cause. In fact, this was one of the reasons they were invited to Estonia.

A. M. Tallgren, a member of the museum board at ENM, envisioned a Finno-Ugric department there. He wrote about the Finno-Ugric “tribes” who had not yet become a “cultured people” and about the academic “colony” ranging over the Ural Mountains and to the Arctic Sea (Tallgren 1923, 42; see also Tallgren 1921).

Likewise, Ilmari Manninen, who was Director of the Museum in 1922-1928, and the lecturer (associate professor) of ethnography at the University of Tartu in 1924-1928, viewed Finno-Ugric studies as a viable future endeavor for Estonian ethnography (Mannien 1924, 527-528).

1929 saw the publication of Manninen’s comprehensive, textbook-like work, Soome sugu rahvaste etnograafia (“The Ethnography of Finno-Ugric Peoples”)4, which drew upon the lectures delivered at Tartu University and focused on the material culture of Finno-Ugrians. For Manninen, ethnography primarily meant studying material culture, mainly that of peasants (Manninen 1924). This work remained a staple among ethnography scholars for some time, and the ethnographers who set out to the Veps’ villages in the 1960s were familiar with it. In the chapter on the Veps, Manninen quotes the Finnish linguist Lauri Kettunen who describes his arrival in the very traditional southern Veps village of Arskaht´ in the winter of 1917-1918: “I instantly realized that I had arrived in that proto-Finnish dream-world that I had so often dreamt of, if only for a moment, to visit.” (Manninen 1929, 57). These lines reflect the evolutionist ideas of Finno-Ugric cultural cohesion, common among the Finnish humanitarians, studying their linguistic relatives in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (Niiranen 1992, 28-33). They believed that the study of far less developed, yet kindred peoples could offer insight into the way one’s people, who had advanced to the state of a “cultured people,” had once lived in the past. It is likely that these lines also inspired the Estonian ethnographers of the 1960s.

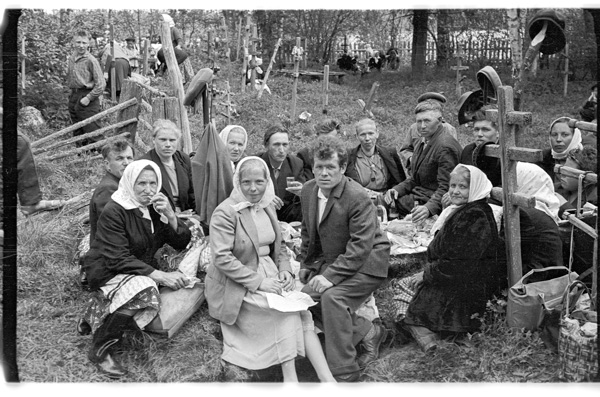

Illustration 1. The Veps commemorate their dead on the graves. Peloo cemetery, Boksitogorsk rayon, Leningrad oblast. Photo by Ants Viires, 1965. ERM.

Nevertheless, under Manninen’s guidance, the primary research focus lay on Estonia and Estonians, with the adjoining areas and kindred peoples forming a backdrop. Finnish and Estonian scholars could study very few Eastern Finno-Ugrians at the time, as the relations with the Soviet Union on the one side and Estonia and Finland on the other side were strained, if not hostile. Only the Livonian coast in Latvia, Estonian Ingria, and Finnish Karelia were available for Estonian scholars. During World War II, they took some trips to the Votians in German-occupied Ingria (Leningrad Oblast). It was only from the 1960s that the grand research plans of Tallgren and Manninen became feasible for Estonian ethnographers.

In the wake of World War II, Estonia was annexed by the Soviet Union. The political border separating Estonian ethnographers from their eastern linguistic relatives disappeared, but this did not foster a Finno-Ugric research boom. From the 1930s, the government-supported pseudo-scientific “new teaching of language,” or the Japhetic theory of Nikolay Marr, dominated the Soviet Union. This theory affected the related disciplines of archeology and ethnography (see Alymov 2014, 124-125). Marr and his followers denied the concept of linguistic families and language trees with proto-languages and language branches developed in the traditional comparative-historical linguistics. Consequently, there were no Finno-Ugric languages (nor peoples), and studying them was branded anti-Soviet by the establishment. At the same time, comparative-historical linguistics was viewed as a “bourgeois science.“ Paul Ariste5, a renowned linguist, who worked as a Professor at the University of Tartu at the end of the 1940s, wrote in his memoirs: “Lectures had to be delivered in the vein of Marr’s linguistic theory. […] It was downright dangerous to talk about linguistic kinship and proto-language” (Ariste 2008, 277).

Thus, the concept of Finno-Ugric linguistic kinship, which had influenced Estonian ethnography, was stigmatized as being bourgeois. One of Tallgren’s students, the archeologist Harri Moora6, sought to readjust ethnography to fit the new Soviet circumstances. Moora, likewise Ariste, was an Estonian patriot but felt compelled to criticize the excessive preoccupation of “bourgeois Estonian ethnography” with Finno-Ugric ties (Moora 1947, 33-34). In reality, Estonian ethnography of the 1920s and 1930s was hardly preoccupied with the Finno-Ugric relationship, and Moora was well aware of this. However, for the Estonian ethnography to survive in the conditions of Marr’s overarching theory, one had to decry the previous “bourgeois” tradition. Such a distancing was essentially a rhetorical move (see Jääts 2019, 5).

It was impossible to advance Finno-Ugric studies while Marr’s doctrine reigned, but the study of individual Finno-Ugric languages and peoples did continue. Despite comparative historical linguistics being officially condemned in the Soviet Union, it never entirely disappeared. In 1947, under the initiative of a renowned linguist Dmitri Bubrich, a Soviet-wide Finno-Ugric conference was held in Leningrad. Among other things, the scholars of Leningrad and Estonia divided the Baltic-Finnic languages between themselves. It was decided that Estonians would focus on the Estonian, Livonian and Votian languages. In the summer of the same year, Ariste set out with some students to visit the Votians (Ariste 2008, 277-278, 280). From that trip, he purchased an icon cloth to augment the ENM’s Finno-Ugric collections (B 44:1, see ERM Peakataloog B2, pp 23-24).

Finally, in the summer of 1950, Stalin withdrew his support of Marr’s theory, and it was quickly discarded. It was again possible to talk freely about Finno-Ugric linguistic kinship. The department of Finno-Ugric languages at the University of Tartu headed by Ariste was rejuvenated, and it became a very influential research center in the Soviet Union and beyond (Ariste 2008, 290-295).

Ariste’s energy would ultimately inspire ethnographers as well. Ariste, who was quickly gaining academic authority, maintained close contact with the Museum of Ethnography. From 1953-1958 he was a member of the museum’s research board. In addition to language, Ariste was also interested in traditional folk culture and brought many Finno-Ugric artifacts back from his expeditions. Other linguists followed suit. Their contributions were published in the museum’s yearbooks.

The Recovery of Finno-Ugric Studies

The recovery of Finno-Ugric studies in Estonian ethnography took time. The Estonian National Museum went through some chaotic times after the war (see Astel 2009). There were no resources that would allow researchers to undertake fieldwork trips in Estonia, let alone other Finno-Ugric areas. In 1952, a small group of ethnographers was formed in Tallinn, within the archeology section of the Institute of History at the Academy of Sciences of the Estonian SSR. It was H. Moora´s initiative. This group became the center of excellence in ethnography for Soviet Estonia. For many years the group was headed by Ants Viires7. Tallinn’s ethnographers played a vital role in the directing of ENM, as from 1946-1963, the museum was under the jurisdiction of the Academy of Sciences. However, Tallinn’s ethnographers did not turn much attention to Finno-Ugric peoples in their research, and there were no collections of ethnographic objects in Tallinn. Thus, the revival of the Finno-Ugric studies remained a task of the Museum of Ethnography in Tartu. The process started at the end of the 1950s.

In January 1957, the ethnographers of the Academy of Sciences convened in Tartu. Harri Moora, and possibly, Ants Viires led the discussions. The subject revolved around the need to collect “rapidly vanishing ethnographic materials.“ Estonian ethnographers decided to work among the neighboring peoples too, including the Votians and Izhorians. The use of film to record the immediate environment and labor processes was also proposed (ETA 1/10/65, p 4-6). Academy’s Presidium approved the decisions of the meeting in December 1957 (ETA 1/1/376, pp 186, 190, 192). This created an opportunity to extend the ethnographic fieldwork to the eastern Baltic Finns.

The opening of the exhibition titled “Examples of Finno-Ugric Folk Art in the 19th Century” at the Museum of Ethnography in 1957 was the first sign of recovery of Finno-Ugric studies in Estonian ethnography. The exhibition was taken down only in 1960 after the museum’s 50th-anniversary celebrations in 1959 (Linnus 1970b, 244; Konksi 2009, 350).

As far as we know, the first Finno-Ugric research trips of Estonian ethnographers after World War II were made to the Karelians, Votians, and Izhorians as a part of integrated complex expedition of the Baltic republics under the direction of Moscow (Viires 2011, 99-100, 104-105, 108). The academic results of these trips remained scarce.

The first researchers from the ENM were Aino Voolmaa and Kalju Konsin. The latter joined the Finno-Ugric languages students at the University of Tartu on their expedition to Valdai Karelians in 1962. Voolmaa accompanied the language students from the university when visiting northern Veps villages in 1962 and central Veps villages in 1963.

One of the factors facilitating the recovery of Finno-Ugric studies was the restoration of contacts between Finnish and Estonian ethnographers at the end of the 1950s and early 1960s (see Luts 1999, 13-14, 34; Konksi 2009, 270). Finns were interested in Estonians as kindred people, and this interest extended to eastern language relatives. The visits of Finnish colleagues, such as Kustaa Vilkuna, Toivo Vuorela, Niilo Valonen, and others, were of crucial importance for Estonian ethnographers, virtually cut off from the “bourgeois” western world during the postwar decade. Having lost the war, Finland was a “bourgeois country” because it was capitalist, enjoyed extensive academic freedom, and had research contacts with the West. At the same time, the USSR controlled Finland and considered it a friendly country. That is why Finns were allowed to visit the Estonian SSR. Contacts with Finnish colleagues helped spread ideas and invigorate the professional self-confidence of Estonian ethnographers.

In March 1964, the Finnish President Urho Kaleva Kekkonen visited the Estonian SSR, including Tartu. The following summer, the ferry connection between Tallinn and Helsinki was restored. In August 1965, the Second International Congress for Finno-Ugric Studies took place in Helsinki. For the first time, a large delegation from the Estonian SSR was able to participate (more of its importance below). Thus, the Iron Curtain lifted a bit, allowing some fresh air.

The Academic Framework of the Veps Expeditions

In the Soviet Union, ethnography was seen as a sub-discipline of history encompassing studies of peoples and their culture, specifically their material culture (livelihood, buildings, settlements, clothing, food, etc.). The theoretical foundation for this was historical materialism, which drew upon Lewis H. Morgan and Friedrich Engels’ evolutionary ideas, according to which the impetus behind the development of human society is progress in the production of material goods. By the mid-1940s, when Estonian ethnography was merged with the Soviet one, the latter had been developed into a firmly controlled centralized system overseen by the Institute of Ethnography of the USSR Academy of Sciences in Moscow. One of the main themes in Soviet ethnography was ethnogenesis, or the formation and development of ethnic groups (tribes, peoples, nations), studied in cooperation with archeology, history, linguistics, folklore studies, and physical anthropology. Ethnogenesis became necessary because, in Stalin’s view, peoples or ethnic groups were the primary subjects of history. The history of the Soviet Union was the total of the histories of the Soviet peoples and began with the origins and development of those peoples (Abashin 2014, 152-153). The role of ethnographers was to study in detail traditional folk culture in order to learn about the ethnic history of peoples and their cultural interactions with their neighbors. Estonian ethnographers were effective contributors to the research of ethnogenesis. Estonians’ most outstanding achievement was a collection of articles edited by Harri Moora Eesti rahva etnilisest ajaloost (“On the Ethnic History of Estonian People,”1956). The volume was quickly translated into Russian8 and became a model for other similar studies in the Soviet Union and elsewhere.

In 1960, the first International Congress for Finno-Ugric Studies was held in Budapest. Gyula Ortutay, the rector of the University of Budapest, highlighted the need to study the ethnogenesis of all Finno-Ugrians in his opening speech. He also pointed to the Soviet (resp. Estonian) achievements in this regard. Paul Ariste and a couple of other Estonian linguists participated at the conference as members of the Soviet delegation. Estonian ethnographers were not present (Ahven 2007, 270; Congressus 1963, 11-19).

A new research trend in Soviet ethnography at the end of the 1940s focused on studying contemporary socio-cultural processes. Ethnographers were expected to positively reflect the socio-economic changes under Soviet rule (e.g., industrialization and the collectivization of agriculture) and to actively contribute to building a socialist society (e.g., participation in the atheistic struggle and the creation and implementation of new Soviet traditions). Estonian ethnographers sought to avoid dealing with this contemporary, socialist environment as much as possible, preferring to focus on a relatively apolitical past. Popular research eras were the second half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th (see Konksi 2004; Konksi 2009, 311-326; Jääts 2019, 8). This tendency reveals itself eloquently in the Estonians´ research of Finno-Ugric peoples, including the Veps.

According to the leading theorists of Soviet ethnography, the most notable contemporary ethnic process in the Soviet Union was the interethnic integration that manifested in the cultural approximation between peoples. In terms of material culture, this meant an abandonment of archaic, traditional, and primitive culture elements in favor of modern, standardized industrial production (Bromlei, Kozlov 1975, 535-536).

It meant that those interested in traditional peasant culture, for example, in the context of ethnogenesis studies, had to hurry. The old ways needed to be preserved for science as quickly as possible before they completely disappeared from the arena of history. The tradition of “rescue ethnography” dating back to the late 19th century proved vital in new circumstances. From the point of view of Estonians’ ethnogenesis, this applied to the traditional culture of Estonians, neighboring areas and kindred peoples (Peterson 1969, 319; Peterson 1970a, 10-11; Peterson 1982, 6).

General Overview of the Veps Expeditions

In 1962-1963, the employees of the ENM participated in the linguistic expeditions of Tartu University. In 1965 ethnographers Ants Viires and Aleksei Peterson9 joined an expedition organized by physical anthropologists of the Estonian Academy of Sciences. Viires did not return to the Veps, but this trip inspired Peterson, and he initiated a series of museum expeditions to the Veps villages lasting until the early 1980s.10 Aleksei Peterson acted as the leader and the leading ethnographer of those research trips. Occasionally, some other scholars and students interested in ethnography also participated.

Thus, in 1962 a trip was made to the northern Veps (the Karelian ASSR), in 1963, to the central Veps, and in 1965, to the southern and central Veps (in the eastern part of Leningrad Oblast). Afterward, Estonian ethnographers kept returning to the remote and relatively isolated southern Veps villages that had preserved many archaic traits despite being organized into Soviet-style collective farms (kolkhozes, sovkhozes) already in the 1930s. In 1970, the museum extended its research area to include the central Veps living along the western edge of Vologda Oblast. Another research team was working in parallel among the southern Veps.

The expedition staff of the trips arranged by the museum ranged from two to six people. In addition to a researcher or an ethnographer, there was always a photographer, who could also serve as a camera operator (or vice versa), and as a rule, an artist. Collective fieldwork was the norm for the then Soviet and Estonian ethnographers. Trips were made primarily in summer (Dragadze 1978, 66).

Table 1. Materials collected on Veps expeditions (1962-1970)

|

1962 |

1963 |

1965 |

1966 |

1967 |

1968 |

1969 11 |

1970 12 |

|

|

objects |

17 |

33 |

16 |

3 |

72 |

29 |

51 |

30 |

|

drawings |

23 sheets |

28 sheets |

numbers unclear |

- |

83 sheets |

50 sheets |

123 sheets |

79 sheets |

|

ethnographic description |

69 pp |

139 pp |

- |

- |

199 pp |

- |

- |

196 pp |

|

photos |

59 |

108 |

332 |

274 |

351 |

284 |

245 |

236 |

|

film |

- |

- |

- |

900/1800 m |

3000/4000 m |

2500 m |

numbers unclear |

- |

Veps and Estonians: Relations and Attitudes 13

Northern Veps were quite used to strangers and welcomed the Estonians. This was also the case in central Veps villages where Estonians were known and trusted, as Voolmaa writes (EA 97, pp 128-129).

The same, however, could not be said of the remote southern Veps villages that Estonian ethnographers visited for the first time. In this area, they were often met with a great deal of distrust. Many Veps had been intimidated by the repressions at the end of the 1930s and were still wary of contacts the authorities might consider suspicious. The locals declined to be photographed; they hid in their houses, locked the doors, and demanded documents from the strangers. Often, the southern Veps could not immediately understand the point of the ethnographers’ work and activities. Ethnographers had to explain (Tihemets 2015; see also Ants Viires, 19th June 1965).

Once the ice was broken, however, Estonians received a warm welcome. They were offered food, drink, and shelter and allowed to saunas. Veps and Estonian languages are pretty similar, and when the Veps discovered this, they took great pleasure in finding common words and bonding in the process. At times Estonians were even treated as “old relatives” (Tihemets 2015).

During holidays, the Veps drank for days on end, especially the menfolk. Compulsory labor days for the collective farms were carried out in advance to avoid problems (Pedak 2018). This habit dampened the ethnographers’ work. It was impossible to obtain reliable data from drunk men, who kept offering vodka and homemade beer, begging to be photographed and talking rubbish.

By returning to the same places over the years, the ethnographers managed to build up good contacts and friendships. At Sodjärv (Sidorovo)14, where the Estonian ethnographers had a “base camp” for many years, they were almost like locals. The researchers went to parties, visited people, and helped to mend radios and boat motors. There were also romantic liaisons between young Estonian men and the local girls.

The Ethnographers’ Land of Fairy-Tale

Following their research themes (material side of traditional peasant culture, ethnogenesis) and general academic outlook, the Estonian ethnographers set out to Veps villages searching for old and archaic things. In her field diary from the central Veps village Järved (Ozera) on 8th of July 1963, Aino Voolmaa wrote: “There is plenty of ethnographic material here. It is a fairy tale land. Such antiquities have been preserved here that we will never find in our own country anymore” (TAp 544; see also EA 97, p 129). Ants Viires admired the “ancient ways” of Rebagj (Rebov Konets, 21st June1965) and noted with some disappointment that in Ijavad (Bakharevo), “one can sense a stronger impact of modern civilization than in the southern villages” (23rd June 1965).

Estonians saw Southern Veps village people as “a kind of ancient community” (Lepp et al., 2nd April1968). People ate from a common bowl, “according the old custom” (Lepp et al., 5th April1968). The village offered some beautiful scenery “like in an old fairy tale” (31st August 1969 TAp 575).

The researchers were impressed by slash-and-burn fields, harrows made from halved spruce tops, harvesting with sickles, sledges, sleighs that were also used in summer etc. Field diaries leave an impression that central and southern Veps villages served as a sort of living open-air museum for Estonian ethnographers, offering a glimpse into the past of not only the Veps but also the Estonians.

Thus, Estonian ethnographers had a somewhat idealizing view of the Veps villages. Simultaneously, as cultured urbanites, they saw the contemporary Veps area as a backward rural hinterland. Modern phenomena and more recent (socialist) achievements of the Veps did not interest the Estonian ethnographers. New large cattle farms and kolkhoz (or sovkhoz) houses were seldom photographed. The gradual Russification of the Veps was upsetting to the researchers. Voolmaa noted that young and middle-aged Veps preferred to interact in Russian and sometimes even were ashamed of using Veps. In some cases, the younger Veps marked “Russian” or “Karelian” as their ethnicity in their passport (EA 97, pp 59-60; Voolmaa 1967, 215). Erika Pedak also recalls southern Veps’ voluntary changing of ethnicity in their passports; Estonians discussed it among themselves during fieldwork (2018).15 Estonians, facing Soviet nationalities policy themselves, felt sorry for the Veps, who were in a much weaker position in the Soviet hierarchy of ethnic units. Estonian ethnographers did not welcome the assimilation of a close-kindred people and the disappearance of their language.

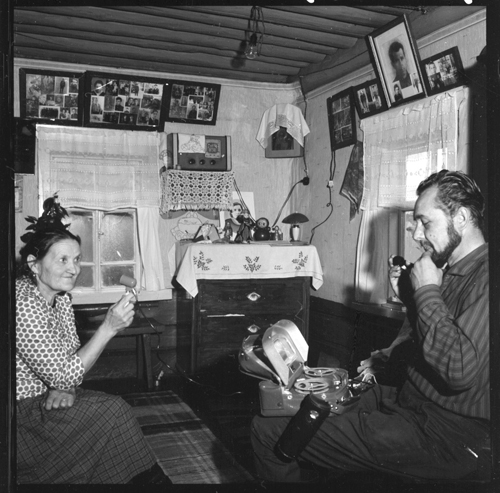

Illustration 2. Toivo Pedak recording a Veps woman. Krasnyi Bor, Boksitogorsk rayon, Leningrad oblast. Photograph by Aleksei Peterson (?), 1967. ERM Fk 1580:81

Work on the Field

Since Estonian ethnographers were primarily interested in the past, they used their ears rather than their eyes (see Dragadze 1978, 66). Participatory observation is of little use when examining the past. The present was of interest only insofar as it contained archaic traits. Thus, informants were picked from among older people who remembered as things were before. An ideal interviewee was a Veps, who was as old as possible, sober, intelligent, and talkative. The interviews could last for hours. Information of interest was written down, partly recorded. The conversation proceeded mainly in Russian, more seldom in Veps (Pärdi 2019). Erika Pedak recalls that Peterson knew many Veps words and tried to use his rudimentary Veps, as it helped break the ice (2018).

One of the avenues through which the Veps language entered conversation was the Veps names of objects and details that fascinated the ethnographers (Võime 2017) because they were significant for the study of cultural contacts and ethnogenesis.

In 1962-1963, Aino Voolmaa sought to expand the virtually non-existent Veps collection for the ENM, although it was too difficult to transport more oversized items. Her main interest was in textiles and clothing, which were also easier to bring back.

During the 1965 and 1966 expeditions, the collection of objects was not the primary objective, but ethnographers brought back some artifacts of interest received as gifts or found in abandoned buildings. These were primarily tools and everyday items, and some clothes. In the ensuing years, the collecting of artifacts was prioritized and was relatively successful. Over half of the objects were received as gifts; the rest were bought. However, not every item that the ethnographers desired was readily given up, not even in exchange for money. These particular objects were instead drawn or photographed.

Ethnographers wrote down stories of the collected objects and packed them up. Most of them were sent to the museum by post. More oversized items (plows, wagons, sleighs) could not be collected at the time, for it would have been problematic to transport them to Estonia (see Lepp et al.1968, 2 nd April). Furthermore, the museum lacked sufficient storage space. However, the long-term objective, which scholars pursued from the beginning, was to obtain a representative material overview of the traditional Veps folk culture (see Linnus 1970b, 245). Ethnographic objects were seen as research objects, analyzed and used to solve a particular research question. To be sure, these things also served an illustrative and popularizing function and could be displayed at future exhibitions.

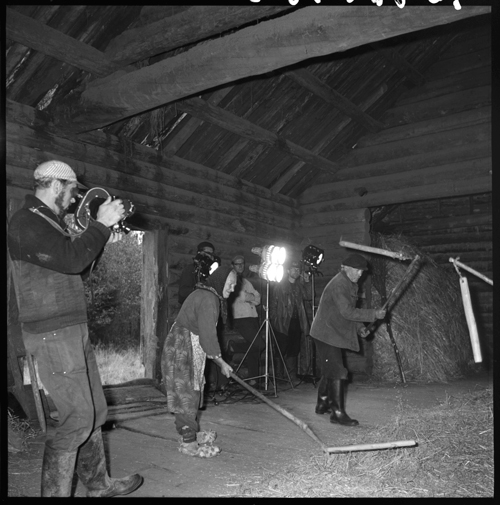

The 1966–1969 southern Veps expeditions were noteworthy for recording old and supposedly rapidly vanishing work practices and habits with a camera.16 Film recording during fieldwork had already been advised by the conference of the ethnographers of the Academy of Sciences in Tartu in January 1957. Although no provisions had been made for the Soviet museums to make films, it was not downright prohibited either.

The significance of ethnographic films was likewise discussed at the Fenno-Ugric congress in Helsinki in August 1965, which Peterson also attended. According to the Hungarian ethnographer, László Keszi-Kovács, the ethnographer’s film was as crucial as tape for a linguist. He emphasized the importance of filming work practices and rituals and proposed the foundation of a central Finno-Ugric film archive in Helsinki or Budapest (Hallap, Tedre 1965, 700).

Estonian ethnographers started to use a film camera (35 mm Konvas) in the Veps area in 1966. The primary focus of the expedition was slash-and-burn agriculture. In subsequent years Peterson’s crew filmed harvesting with a sickle, grain thrashing with a flail, haymaking, potato planting, letting out and bringing in the cattle, cooking, beer making, people whisking themselves with branches in a bread oven, the building of a dugout, washing laundry, making birch bark shoes, linen scutching and spinning with a spindle. They also filmed a village celebration in Sodjärv and the Peloo (Pelushi) graveyard. In Soviet academia, spiritual life was a rule, the concern of folklorists and not ethnographers. However, in Veps villages (and subsequently in other Finno-Ugric areas), its aspects were recorded to some extent.

Two films, “The Making of Dugout Boats” (1980) and “Vepsians at the Beginning of the 20th Century,” were subsequently put together using the materials filmed in the Veps villages in 1966-1969 (and later).17

Illustration 3. Darya Smirnova and Stepan Smirnov are demonstrating threshing. Toivo Pedak is filming. Laht, Boksitogorsk rayon, Leningrad oblast. Photograph by Aleksei Peterson, 1967. ERM Fk 1580:153

Academic Results of the Veps Expeditions

The first three expeditions discussed in this paper (1962, 1963, 1965) were somewhat accidental: the ethnographers simply seized the opportunity and joined the expeditions of linguists and physical anthropologists. There was an interest in linguistic relatives, but at the time, the ENM had no such research topic officially.

Estonian ethnographers, including A. Peterson, attended the Second International Congress for Finno-Ugric Studies, held in Helsinki in August 1965. A. Voolmaa was also present. Trips abroad were coveted and perceived as a privilege in the Soviet Union of those times. To travel outside Soviet borders, especially to capitalist countries, Soviet citizens had to pass a thorough preliminary check. For example, A. Viires did not get permission to go to Helsinki this time. His article on land transportation of the Baltic Finns (incl. the Veps) was still published in the congress volume (Viires 1968). It is worth mentioning that Viires refers to the academic literature published in the 1950s and 1960s in West Germany, Austria, Norway, and Sweden there. It is exceptional in the Soviet Estonian ethnography of those decades. It turns out that he had some kind of access to the Western works, probably through the Academy of Sciences. Ethnographers working at the ENM were in a much worse position in this respect. ENM was transferred under the Ministry of Culture’s auspices in 1963, and academic activity was not encouraged there anymore. It continued mainly on A. Peterson´s initiative.

Let us turn back to the congress in Helsinki. Other participants included Toivo Vuorela, Niilo Valonen, Kustaa Vilkuna, and of course, Harri Moora. Moora delivered one of the four plenary presentations, titled “Earlier Farming History of Estonians and the Neighboring Peoples.” He discussed the development of agricultural technology in detail. Kustaa Vilkuna talked about Finnish plow types (Hallap, Tedre 1965, 698, 700-701). Without a doubt, Peterson listened carefully to these presentations. As for the next congress (Tallinn, 1970), he delved into the history of the fork plow based on his field experience in Veps villages (Peterson 1970b).

The international academic congress indeed served as an inspiration to Estonian scholars, including the ethnographers. They saw that Finno-Ugric peoples and languages were of interest to foreigners, mainly of course to the Finns and Hungarians. However, foreigners were generally not allowed to do fieldwork in the Soviet Union. Therefore, Estonians were at an advantage and made full use of this in subsequent decades. In a way, Estonian scholars could continue the fieldwork tradition of their Finnish and Hungarian predecessors of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

By and large, it was a common feature of Soviet ethnography that regional research institutions were concerned only with their particular region (SSR or ASSR), while the Moscow-based Institute of Ethnography of the USSR Academy of Sciences enjoyed the privilege of conducting fieldwork throughout the entire Soviet Union as well as abroad. The trips that the Estonian ethnographers made to the Finno-Ugric peoples were an exception to this rule. It was tolerated, but later on, it became the source of tensions. What ultimately resolved the problem, and what was used later on, was a collaboration with the local, regional museums. Estonian ethnographers lacked such a partner in the central and southern Veps villages, as the Veps did not have territorial autonomy nor the respective institutions, including a regional museum.

From 1966 onwards, research trips to the Veps area were initiated and arranged by the ENM. It was A. Peterson´s initiative. He has read a recent book by Soviet Russian ethnographer Vladimir Pimenov on the Veps ethnogenesis (Vepsy: Ocherk etncheskoi istorii i genezisa kul´tury . Moskva-Leningrad, 1965) and discovered that Pimenov´s arguments had been based mainly on the evidence of archaeology and folkloristics. The material side of the Veps peasant culture has remained almost unstudied, and Peterson saw his niche and mission there. On 21 October 1966, the museum’s research board discussed the future work plan for 1967-1970. Director Peterson spoke about the increase in the role of Baltic-Finnic ethnography and underlined its international scope (ERM 1/1/223, p 6). The plan was approved.

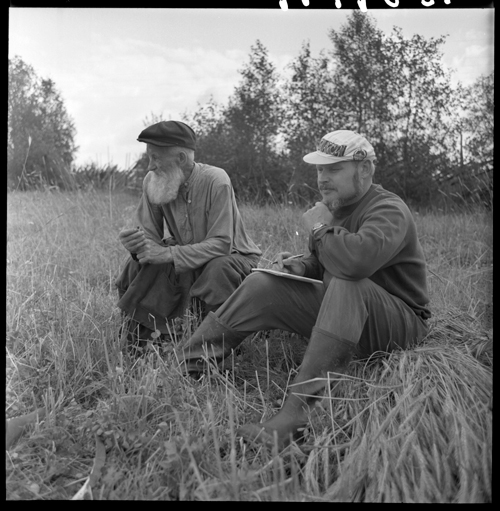

Illustration 4. Village people. Noidal, Boksitogorsk rayon, Leningrad oblast. Photograph by Vello Kutsar, 1968. ERM Fk 1581:510

This new direction was inaugurated by Aino Voolmaa’s article “Observations on Veps Clothing and Women’s Craftwork” in the XXII Yearbook of the ENM (1967). Voolmaa’s discussion of the Veps women’s and men’s clothes and the related handicrafts extends to modern times. Nevertheless, it seems that she was more interested in older layers of culture such as the “developmentally ancient” handicraft tools and methods (e.g., the carding bow preserved in places in central Veps villages and spindles used instead of spinning wheels) which were “valuable for solving research questions concerning several other peoples as well” (1967, 216, 236).

The Third International Congress for Finno-Ugric Studies was held in Tallinn in August 1970. A significant event took years to prepare for and had a profound impact on Estonian ethnographers. For the Museum of Ethnography, 1970 turned out to be a banner year for Finno-Ugric studies. To mark the congress, the museum organized an exhibition of Estonian folk art in Tallinn’s Art Hall. During their trip to Tartu, the congress participants became acquainted with the Museum’s work and attended an exhibition on Finno-Ugric folk art, organized in connection with the congress (Ahven 2007, 501-502; ERM A 1/1/223, p 24).

The annual spring conference of the ENM was also dedicated to Finno-Ugric peoples that year. Peterson delivered a presentation on the Veps’ primary grain drying methods, based on his recent fieldwork (Peterson 1970c, 9-10). Hugo Puss discussed some old and new things found in the households of southern Veps (Puss 1970).

The XXIV Yearbook of the ENM was also linked to the congress in Tallinn.18 The volume mostly contained articles related to Estonia, which was fitting since Estonians are also Finno-Ugrians. However, Peterson’s paper on Veps barn was primarily based upon the material collected on Veps villages’ trips in 1965-1968 (Peterson 1969, 319).

The ENM also published a collection of articles for the occasion titled Läänemeresoomlaste rahvakultuurist (“On the Folk Culture of Baltic Finns”). The publication paid tribute to Ilmari Manninen, a man “who had established Estonian ethnography and who consistently emphasized the need to research Baltic-Finnic folk culture” (Linnus 1970a, 5; see also Linnus 1970b, 230-231). In Stalin’s time, it would have been unthinkable to acknowledge a “bourgeois” ethnographer in such a way. Times had changed indeed – it had become possible to underscore the continuity of Estonian ethnography and its Finno-Ugric studies.

The collection also includes two articles by Peterson. The first was a programmatic opening piece, “The Tasks of Estonian Ethnographers in Researching Baltic Finns” (Peterson 1970a), while the second, “Supplements to the History of the Estonians’ and Veps’ Forked Plough,” was primarily built upon the material collected during the 1966-1968 fieldwork among the central and southern Veps (Peterson 1970b, 41). As the author put it: “The idea to write this article came about while working with a forked plow on the slash-and-burn field during the southern Veps expedition” (ibid, 59). The history of agriculture and agricultural tools was an important research topic, and several influential academics, including Kustaa Vilkuna and Harri Moora, were dealing with it. Leading scholars shared the idea that the forked plow was a relatively recent borrowing from the eastern Slav or Baltic neighbors (the beginning of the 2nd millennium C.E.). Peterson claimed that this type of plow was closely linked to slash-and-burn farming and had been invented in mainland Estonia at the beginning of the 1st millennium C.E., from where it later spread to the Veps. In particular, he highlighted the substantial similarity between the southern Veps and southeastern Estonian forked plows (Peterson 1970b).

At the congress, Peterson presented ethnic traditions in the Baltic Finnic buildings, including the Veps’ material (Peterson 1970d).

Thus, the Third Congress for Finno-Ugric Studies was a success and doubtless inspired Estonian researchers to continue their Finno-Ugric themes. In the next yearbook of the Museum (XXV, 1971), Peterson published his article, “Southern Veps Flax Production,” which, again, primarily drew upon the material collected on the 1968-1969 trips to southern Veps villages. Peterson regarded flax cultivation among the Baltic Finns as an ancient phenomenon closely intertwined with slash-and-burn agriculture (Peterson 1971).

Peterson liked to emphasize the antiquity and local provenance of the phenomena examined. He tended to defend Baltic-Finnic creativity against the theories of Slavonic and Baltic cultural borrowings. Perhaps he expressed his Estonian patriotism, and his sympathy to the Baltic Finns in this way.

Illustration 5. Fedor Saponchikov and Aleksei Peterson (right) talking about agriculture. Arskaht’, Boksitogorsk rayon, Leningrad oblast. Photograph by Vello Kutsar, 1969. ERM Fk 1581:41

Conclusion

Since the beginning of the 20th century, Estonian ethnographers have had a permanent interest in Finno-Ugric peoples. After World War II the border, separating Estonians from their eastern language relatives was opened, but Finno-Ugric studies could not flourish due to Nikolay Marr’s ideas, which predominated until 1950. The shortage of personnel and the internal confusion within the Estonian ethnography inhibited the revival of Finno-Ugric studies. In the 1960s, the ENM in Tartu, headed by Aleksei Peterson, emerged as the center for Finno-Ugrian ethnography in Estonia. Research trips to eastern language relatives were first undertaken under the initiative and support of linguists (predominantly Paul Ariste) but continued independently.

This article sought to examine Estonian ethnographers’ expeditions to Veps villages in 1962-1970. The preferred destination of Estonian researchers was the isolated southern Veps area. It was there that much of the archaisms that fascinated ethnographers (e.g., slash-and-burn agriculture, carving of dugouts, sauna whisking in the bread oven) had been preserved or only recently lost. For Estonian scholars focusing then on ethnogenesis, the Veps villages offered, as it were, a window into the past. These villages’ material culture had not been widely researched, and Peterson saw both an opportunity and mission. Old things were disappearing with modernization. Ethnographers had to act quickly to save what they could for science. Thus, they filmed and photographed as much of the Veps traditional peasant culture as they could. They also conducted ethnographic interviews, made drawings, and diligently collected artifacts.

The fieldwork material rapidly reached the academic arena, papers were delivered at international, regional, and domestic conferences, and scholarly articles were published in different languages (primarily Estonian, Russian, and German). The expeditions received vivid coverage in the Estonian media. Newspapers printed shorter and longer stories on the ethnographers’ work in Veps villages, and it was discussed on TV too, at least once. There must have been some interest among the audience. The study of linguistic relatives received a positive response in Estonian society because it was associated with the national identity.

The overall impact of those and subsequent expeditions on the Veps themselves is difficult to assess. It is most likely that the visits of the Estonian researchers bolstered their ethnic self-esteem. If the neighboring Russians tended to look down upon the Veps and their language, the Estonian ethnographers studied the Veps for what they were, thereby acknowledging and elevating everything Vepsian, from their ancient peasant culture to the language. Estonians perceived the Veps villages as a sort of Baltic-Finnic fairy tale land, and the participants enjoyed going on expeditions there. They felt that they were doing the right thing, promoting the Estonian cause in a way.

An entire cultural movement sprung up from Finno-Ugric studies in Estonia in the 1970s, including Lennart Meri (President of Estonia in 1992-2001) and his ethnographic documentaries, Veljo Tormis, and his choir music as well as Kaljo Põllu and his graphic art. The highlighting of the Finno-Ugric connections of Estonians offered an opportunity to express one’s Estonian identity independent from the Soviet regime (Eesti ajalugu, 2005, 345-350; Kuutma 2005, 57). The expeditions to Veps villages discussed herein, their results, and their responses formed an essential part of the first stage of this Finno-Ugric current in Estonian cultural history.

Estonian ethnography had been an indubitable part of European ethnology in the 1920s-1930s. Links were closer with Finland, Sweden, and Germany. After World War II, Estonian ethnography was made a part of Marxist-Leninist Soviet ethnography, and its contacts with “bourgeois” European ethnology remained very restricted for political reasons, primarily until the late 1950s. Estonian ethnographers had quite intensive, partly forced contacts with colleagues in Moscow and Leningrad and Soviet Baltic republics. International academic cooperation on Finno-Ugric studies, revived in the 1960s, was essential for the Estonian ethnographers (and other humanitarians) as almost the only way to the world outside the Soviet camp. Besides Soviet scholars themselves, most participants came from Soviet-controlled Finland and Hungary, but they had contacts with their western colleagues and could mediate ideas and literature. Occasionally, academicians from the western countries also took part, including some Estonian scholars in exile. It was probably interesting to talk, despite possible initial distrust. “Sovietness” of Estonian ethnographers was often relatively superficial. Estonian ethnography tended to draw people who valued national roots, traditions, and identity. There was quite a lot of continuity in Soviet Estonian ethnography, including its Finno-Ugric branch.

Notes

1 In Estonia, the discipline concerned mainly with the material aspect of traditional peasant culture was called “ethnography” until the 1990s. Its counterpart in Russia and the Soviet Union, with a somewhat broader focus, was also labelled “ethnography.” I use the term of the era instead of the present term “ethnology.” [ Return to the article ]

2 Estonian National Museum (ENM), founded in 1909 in Tartu, was named the Museum of Ethnography of the Estonian SSR Academy of Sciences from 1952–1963; and the State Museum of Ethnography of the Estonian SSR from 1963-1988. Initial name was restored then. For sake of simplicity, the abbreviation ENM is used throughout the article. [ Return to the article ]

3 Estonian ethnographers’ disciplinary identity has not included Baltic German and Russian scholars´ episodic research on Estonians in the 19th century as a rule. Ilmari Manninen (1924, 527), the founding father of Estonian ethnography, has stressed that ethnography was actually a new science in Estonia, created as an academic discipline only in the 1920s. From Estonian perspective, the Finno-Ugric studies mean research of Finno-Ugric peoples other than Estonians. From international (and Soviet) point of view, the Estonian studies form a part of Finno-Ugric studies. (Most Estonians taking part in Finno-Ugric congresses and conferences made their presentations on Estonian topics.) I depart from the Estonian perspective in this article. [ Return to the article ]

4 The book came out also in Finnish (1929) and in German (1932). [ Return to the article ]

5 Paul Ariste (1905–1990), Estonian linguist, a Professor at the Tartu University (since 1949), member of the Academy of Sciences of the Estonian SSR (since 1954), Scientist of Merit of the Estonian SSR (1965). [ Return to the article ]

6 Harri Moora (1900–1968) was an Estonian archeologist, a Professor at Tartu University (from 1938–1950), a member of the Academy of Sciences of the Estonian SSR (since 1957), a Scientist of Merit of the Estonian SSR (1957). Professor Moora’s central role in shaping ethnography in the post-World War II Estonian SSR was due to the fact that all prominent ethnographers had perished or escaped to the West. It should come as no surprise that an archaeologist would deal with ethnography in the Soviet context, for both archeology and ethnography were seen as auxiliaries of history, the task of which was to study the material culture of pre-capitalist societies. [ Return to the article ]

7 Ants Viires (1918–2015) was an Estonian ethnographer/ethnologist. His academic career was hampered by his short service in the German Army in 1944 for a long time (see Viires 2011, 102). [ Return to the article ]

8 “Вопросы этнической истории эстонского народа“ (Tallinn, 1956). [ Return to the article ]

9 Aleksei Peterson (1931–2017) was an Estonian ethnographer/ethnologist, director of ENM in 1958-1992. Member of the Communist Party in 1957–1990. [ Return to the article ]

10 For the full account of ENM´s research trips to the Finno-Ugrians, see Karm, Nõmmela, Koosa 2008. [ Return to the article ]

11 Including Karelian and Russian villages. [ Return to the article ]

12 Data added from two expeditions made in parallel. [ Return to the article ]

13 The following excerpts until “Academic results of the Veps expeditions” are primarily based on field diaries (TAp 534, 544, 565, 573, 574, 575, 595 and Viires 1965). [ Return to the article ]

14 I prefer to use the Veps place names. Official Russian names are given in brackets. [ Return to the article ]

15 See Jääts 2017 for more on registration of the Veps’ identity in the late Soviet Union. [ Return to the article ]

16 For more on film in ENM, see Niglas, Toulouze 2010; Peterson 1975 and 1983. [ Return to the article ]

17 The films were re-issued on DVD by ENM (The Estonian Ethnographic Film III. Vepsians, 2015) [ Return to the article ]

18 The publication year in the book is 1969, but in reality, it came out in the summer of 1970, just before the congress. [ Return to the article ]

Sources

Archives

ETA = Estonian Academy of Sciences, Archive

- 1/1/376

- 1/10/65

ERM = Estonian National Museum; Archive

- A 1/1/223

- EA 97

- TAp 534, 544, 565, 573, 574, 575, 595 (fieldwork diaries)

- Peakataloog B2 (Main directory)

- Viires, Ants 1965. Vepsa-Karjala ekspeditsioon (fieldwork diary, ERM)

Interviews

Pärdi, Heiki. Interview by Indrek Jääts. February 26, 2019.

Pedak, Erika Interview by Indrek Jääts. February 1, 2018.

Tihemets, Evi Interview by Indrek Jääts. May 5, 2015.

Võime, Lembit Interview by Indrek Jääts. November 29, 2017.

- List item

- List item

- List item

Works Cited

Abashin, Sergey. Ethnogenesis and Historiography: Historical Narratives for Central Asia in the 1940s and 1950s. In An Empire of Others. Creating Ethnographic Knowledge in Imperial Russia and the USSR , edited by Roland Cvetkovski and Alexis Hofmeister, 145–170. Budapest-New York: CEU Press, 2014.

Ahven, Eeva. Pilk paberpeeglisse. Keele ja Kirjanduse Instituudi kroonika 1947–1993 . Tallinn: Eesti Keele Sihtasutus, 2007.

Alymov, Sergei. Ethnography, Marxism, and Soviet Ideology. In An Empire of Others. Creating Ethnographic Knowledge in Imperial Russia and the USSR , edited by Roland Cvetkovski and Alexis Hofmeister, 121–143. Budapest-New York: CEU Press, 2014.

Ariste, Paul. Mälestusi. Eesti Kirjanduse Selts, 2008.

Astel, Eevi. Eesti Rahva Muuseum aastatel 1940–1957. In Eesti Rahva Muuseumi 100 aastat, 186–247. Tartu: Eesti Rahva Muuseum, 2009.

Bromlei, Kozlov = Ю. В. Бромлей, В. И. Козлов, Заключение.Современные этнические процессы в СССР, 530-542. Москва: Наука, 1975.

Congressus = Congressus Internationalis Fenno-Ugristarum Budapestini habitus 20-24. IX. 1960 . Adiuvantibus G. Bereczki, P. Hajdú, G. Képes, Gy. Lázló. Redigit Gy. Ortutay. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1963.

Dragadze, Tamara. “Anthropological Field Work in the USSR.” Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford 9, no. 1 (1978): 61–70.

Eesti ajalugu = Jüri Ant, Mart Laar, Kaido Jaanson, Mart Nutt, Raimo Raag, Sulev Vahtre, Andres Kasekamp. Eesti ajalugu VI. Vabadussõjast taasiseseisvumiseni. Peatoimetaja S. Vahtre. Tartu: Ilmamaa, 2005.

Hallap, Valmen, Ülo Tedre. II rahvusvaheline fennougristide kongress. Keel ja Kirjandus 11 (1965): 698–703.

Jääts, Indrek. Illegally denied: manipulations related to the registration of the Veps identity in the late Soviet Union . Nationalities Papers vol. 45, Issue 5 (2017): 856–872.

Jääts, Indrek. Favourite Research Topics of Estonian Ethnographers under Soviet Rule. Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 13, no. 2 (2019): 1–15.

Karm, Svetlana, Marleen Nõmmela, Piret Koosa (compilers). Auasi: Eesti etnoloogide jälgedes. A Matter of Honour: In the Footsteps of Estonian Ethnologists. Дело чести: по следам эстонских этнологов . Tartu: Eesti Rahva Muuseum, 2008.

Konksi, Karin. Arved Luts ja Nõukogude Eesti kaasaja dokumenteerimine Eesti Rahva Muuseumis. In Eesti Rahva Muuseumi aastaraamat XLVIII, 13–46. Tartu: Eesti Rahva Muuseum, 2004.

Konksi, Karin. Etnograafiamuuseumina Nõukogude Eestis 1957–1991. InEesti Rahva Muuseumi 100 aastat, 250–355. Tartu: Eesti Rahva Muuseum, 2009.

Kuutma, Kristin. 2005. Vernacular Religions and the Invention of Identities Behind the Finno-Ugric Wall. Temenos: Nordic Journal of Comparative Religion 41, no. 1 (2005): 51–76.

Lepp et al. = Lembit Lepp, Toivo Pedak, Hugo Puss, Lembit Võime. Vepsa päevik. In newspaper Edasi, 2–6. April, 1968.

Linnus, Jüri. Saateks. In Läänemeresoomlaste rahvakultuurist, toimetanud J. Linnus, 5. Tallinn: Valgus, 1970a.

Linnus, Jüri. Eesti NSV Riikliku Etnograafiamuuseumi soome-ugri rahvaste etnograafilised kogud. In Läänemeresoomlaste rahvakultuurist, toimetanud J. Linnus, 226–246. Tallinn: Valgus, 1970b.

Luts, Arved. Teel juubelile. Tagasivaade Eesti Rahva Muuseumi 50. aastapäevale ja selle eelloole. In Eesti Rahva Muuseumi aastaraamat XLIII, 11–40. Tartu: Eesti Rahva Muuseum, 1999.

Manninen, Ilmari. Etnograafia tegevuspiiridest ja sihtidest Eestis. Eesti Kirjandus 12 (1924): 527–537.

Manninen, Ilmari. Soome sugu rahvaste etnograafia. Tartu: Loodus, 1929.

Moora, Harri. Eesti etnograafia nõukogulikul ülesehitamisel. In Eesti Rahva Muuseumi aastaraamat I (XV), 24–35. Tartu: Teaduslik Kirjandus, 1947.

Niglas, Liivo, Eva Toulouze. “Reconstructing the past and the present: The Ethnographic Films Made by the Estonian National Museum (1961–1989).” Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 4, no. 2 (2010): 77–96.

Niiranen, Timo. “Pioneers of Finnish ethnology.” In Pioneers. The History of Finnish Ethnology, edited by Matti Räsänen, 21-40. (Studia Fennica Ethnologica 1) Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1992.

Peterson, Aleksei. “Vepsa ait.” In Etnograafiamuuseumi aastaraamat XXIV, 319–334. Tallinn: Valgus, 1969.

Peterson, Aleksei. “Eesti etnograafide ülesandeid läänemeresoomlaste uurimisel.” In Läänemeresoomlaste rahvakultuurist, toimetanud J. Linnus, 9–17. Tallinn: Valgus, 1970a.

Peterson, Aleksei. “Lisandeid eestlaste ja vepslaste harkadra kujunemisloole.” In Läänemeresoomlaste rahvakultuurist, toimetanud J. Linnus, 41–63. Tallinn: Valgus, 1970b.

Peterson = А. Петерсон, Первичная сушка хлебов у южных вепсов. In XII научная конференция государственного Этнографического музея Эстонской ССР, 14-16 апреля 1970 г., Тарту , 9-10. Таллин: «Валгус», 1970c.

Peterson, Aleksei. “Probleme der ethnischen Tradition in den Bauten der Ostseefinnen.” In Congressus Tertius Internationalis Fenno-Ugristarum. Tallinn, 17.-23. VIII 1970. Teesid. Тезисы. Thesen II , toimetanud M. Norvik, 61. Tallinn, 1970d.

Peterson, Aleksei. “Lõunavepsa linandusest.” In Etnograafiamuuseumi aastaraamat XXV, 169–184. Tallinn: Valgus, 1971.

Peterson, Alexei Y. Some Methods of Ethnographic Film. In Principles of Visual Anthropology, edited by Paul Hockings, 185–190. The Hague: Mouton Publishers, 1975.

Peterson, Aleksei. “Vepslaste materiaalse kultuuri kogumisest ja uurimisest.” In Läänemeresoomlaste etnokultuuri küsimusi, toimetanud Jüri Linnus, 5–6. Tallinn: Valgus, 1982.

Peterson, Aleksei = Алексей Петерсон. Этнографический фильм как документ исследования. In Etnograafiamuuseumi aastaraamat XXXIII, 30–35. Tallinn: Valgus, 1983.

Puss = Х. Пуссь, Старое и новое в быту южных вепсов. In XII научная конференция государственного Этнографического музея Эстонской ССР, 14-16 апреля 1970 г., Тарту , 11. Таллин: «Валгус», 1970.

Tallgren = Missugune Eesti muuseum peaks olema? Prof. Tallgreni kõne, peetud Tartu ülikoolis E. r. m. koosolekul. In newspaper Postimees , 27. October, 1921.

Tallgren, A. M. “Eesti muuseum ja soome-ugri teaduse alad.” Odamees 2 (1923): 41–43.

Viires, Ants. “Zur Geschichte des Landtransports bei den Ostseefinnen.” In Congressus secundus internationalis fenno-ugristarum Helisingae habitus 23-28 VIII. 1965. Pars II Acta ethnologica. Adiuvantibus: Maija-Liisa Heikinmäki & Ingrid Schellbach. Acta redegenda curavit Paavo Ravila, 383-391. Helsinki: Societas Fenno-Ugrica, 1968.

Viires, Ants. Läbi heitlike aegade. Tagasivaade minu eluteele. Tartu: Ilmamaa, 2011.

Voolmaa, Aino. “Tähelepanekuid vepslaste rõivastusest ja naiste käsitöödest.” In Etnograafiamuuseumi aastaraamat XXII, 214–239. Tallinn: Valgus, 1967.