Cultural Analysis, Series 1, 2023

Interrogating Social Distancing: Pandemic and Farmers’ Protest in India

Abstract: Drawing from my interviews with protesting farmers on the highways of Haryana, India, the article traces the intertwined relationship between protests against the Farm Laws (2020) and farmers’ reactions to pandemic governance. The article closely examines the contentious repertoire of the protesters to understand how the protesters challenge and change the meanings of such long-standing concepts like home and family, rural and urban, through counter-hegemonic performances. They contest the narratives of a pandemic with narratives of intimacy and togetherness by bringing the home out on the highways. By narrowing the social distance, they also question the imaginary divides that create social hierarchies.

Keywords: pandemic and protest, farmers’ protest, India, coronavirus, social distancing, COVID-19

____________________

Introduction: A Timeline of the Farmers’ Protest in India

India’s National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government (the right-wing political alliance in power led by Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)) proposed three farm bills in the parliament on September 14, 2020. The three farm bills, namely (i) Farmers' Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Bill, (ii) the Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Bill, and (iii) the Essential Commodities (Amendment) Bill came out with the agenda of reshaping the government-run agricultural sector into a private-run sector “to liberalize the agricultural market” (Nigam 2021, 6; Kiran and Suresh 2020, para. 2). Flouting all parliamentary conventions of referring the bills to appropriate standing committees and consulting the stakeholders for scrutiny, the Lok Sabha passed the bills on September 17 (Sahu 2020, para. 4). On September 20, the Rajya Sabha passed the bills by voice vote despite demands for a recorded vote from opposition MPs which could allegedly have defeated the NDA (Ibid., para. 2). In unjustified haste, the three farm bills became farm laws with presidential assent on September 27, 2020.1

During this time, the country was still navigating through the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic. The nationwide lockdown imposed on 24 March 2020 was partially lifted in phases. Considering the struggles to live through the pandemic and nationwide (partial) lockdown, the government anticipated the least resistance from people to this significant change. However, the NDA government’s use of this strategy to make use of the panic created by the pandemic to ram through an agenda with minimal resistance that Naomi Klein calls the “shock doctrine” proved to be severely ineffective (2007, 6). Farmers, laborers, students, and scholars across the country raised their voices in solidarity when the farmers of Punjab and Haryana came out in protest.

Punjabi and Haryanvi farmers were the most vocal because agriculture is the primary means of livelihood in these two states. According to the land-use statistics of 2017-18, the total geographical area under agricultural use in Punjab and Haryana are 84.09% and 85.03%, respectively (Vinayak 2021, para. 2). Before the farm acts were proposed, the farmers in these states benefited highly from the existing mandi system and the government-assured Minimum Support Price. Under the mandi system, farmers brought their yields to the mandi (“market place”) regulated by an Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee. The government purchased farmers’ crops through the Food Corporation of India and other state-level agencies at a Minimum Support Price.

However, the new farm acts did not mention the mandi system though the union government assured verbally that the mandi system would not be affected. The institution of these acts came as a threat to the livelihood of the farmers. In principle, the farm acts would allow individual farmers to enter into a direct contract with private companies. Nevertheless, the farmers have no bargaining power or knowledge of terms of negotiation with private companies. Neither did the farm acts come with an appropriate grievance redressal mechanism (Indian Express Online 2020). The fancy names of the farm laws using such words as “protection,” “empowerment,” “assurance,” and “facilitation” were, in essence, quite misleading. This private turn in the agricultural sector would essentially have left the farmers at the mercy of corporate whims and agri-business competitions.

Therefore, the farmers came out on the streets in protest, disregarding the pandemic protocols instituted by the union government. Initially, the farmers of Punjab and Haryana laid siege to malls, surrounded corporate warehouses, and occupied railway tracks (Nigam 2021, 6). The farmers organized three major campaigns since August 2020 regarding the same issue (Monteiro 2021, 2). First, the public appearance of the farm bills in August 2020 gave rise to more minor factions of protests throughout the country. Second, the Rail Roko (“Stop the train”) campaign was organized by Punjabi farmers’ unions on September 24, 2020.

Finally, the Dilli Chalo (“March to Delhi”) campaign mobilized the farmers of Punjab and Haryana on November 26. Thousands of farmers came out on tractors, trucks, bikes, and cars to stage an indefinite sit-in protest in the national capital region of New Delhi. However, on November 27, when a large group of peacefully marching farmers approached the Singhu border, a border connecting the union territory of Delhi and the state of Haryana, the Delhi Police stopped them with barricades, water cannons, and tear gas shells (R. Kaur 2021, para. 6). Unable to reach Delhi, the farmers camped at the border itself (Nigam 2021, 6). Thousands of farmers blocked the national highways (NH) in protest for a year, until the farm laws were repealed by both the houses of the parliament on November 29, 2021 (for a detailed timeline of the farmers’ protest, see Express Web Desk 2021). This paper explores how the farmers managed to live on the highways for a year when the rest of the world took refuge in a protective cocoon against the pandemic. Through extensive dialogue with the protesting farmers,2 the paper will show why and how the ongoing pandemic failed to terrorize the farmers into abandoning their agenda until the farm laws were repealed.

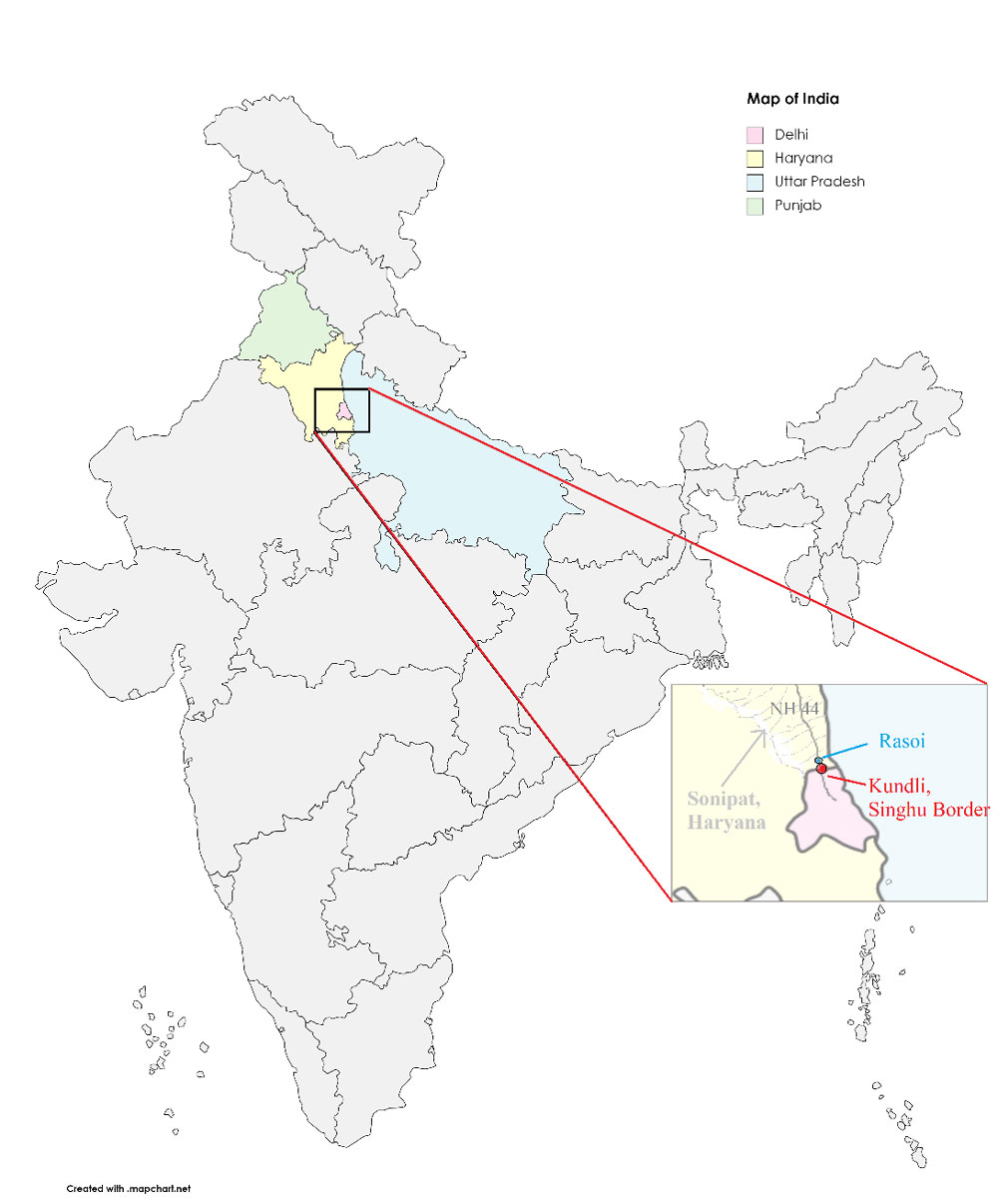

Figure 1: Locating the site of protest on the map of India (map not to scale; created by the author with www.mapchart.net)

Figure 2: “Hail the soldier, hail the farmer! Resist the dark law! [We are] not going back until the [farm] bills are rolled back. Village – Ismailpur, District – Ambala.” – A poster on a truck in Rasoi, Sonipat, Haryana (April 2021)

The article’s central argument is that space of protest is a potential catalyst for erecting non-normative social structures. Collective narratives and performances of resistance at the protest sites contest and subvert the oppressive structures of society and come up with alternative models. As Garlough writes, protesters employ the rhetoric devices of “narratives, rituals, material art, and other aspects of folk culture” to mobilize social movements, advance their agendas and constitute identities (Garlough 2008, 349). For example, the farmers refashioned the Hindu ritual of effigy burning on Dussehra to repurpose it for their protest against the farm laws. Traditionally, on Dussehra, people burn effigies of Ravana, the demon king, in the epic of The Ramayana to celebrate the victory of Lord Rama against evil.

Nevertheless, the protesting farmers burned effigies of PM Narendra Modi on Dussehra (Express New Service 2020, para. 1). They also burnt effigies of prominent corporate figures like Mukesh Ambani, the chairman of Reliance Industries Ltd., and Gautam Adani, the Adani Group’s founder (Kamal 2020, para. 2). Burning their effigies together was an act of condemning the PM for leaving the farmers at the mercy of corporate tycoons. Not just through adaptations of traditions, the farmers created a discourse of contention in every step of their life while living in their temporary homes on the highways. Over the year, oral and performative narratives of resistance spread through word of mouth, social media, and printed and digital public fora. Studying these narratives can help us understand how protests against farm laws during the pandemic lockdown went beyond the agricultural economy and merged with the issues of public healthcare, education system, class struggle, and every aspect of daily livelihood. However, the scope of this paper is limited only to oral narratives collected through ethnographic interviews and news reports.

Pandemic and Protest

Popular resistance is a common and recurring phenomenon in the backdrop of any new change in society (Melucci 1996, 10). While the recent pandemic of COVID-19 itself had a substantial pathological change on human society, governments worldwide instituted more changes in people’s day-to-day lives. As expected, the changes proposed by the pandemic governance in many countries faced incredible resistance from people (Gerbaudo 2020, 66-69). In a 2020 article, Paolo Gerbaudo, an Italian political sociologist, writes about three recent trends in protests that emerged in the US and Europe in the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic. He calls them (a) socially distanced protests, (b) anti-lockdown protests, and (c) pandemic riots (Gerbaudo 2020, 63). Though Gerbaudo’s terminological choices for (a) and (b) are self-explanatory and justified, the category of (c) “pandemic riots” is contestable. He defines the pandemic riots as any protest, movement, or riot that took place during the pandemic but had nothing to do with the pandemic. However, by definition, a riot has to be violent. On this ground, it is highly fallacious that he categorizes the American Black Lives Matter (BLM) protest under the category of “pandemic riots.” More than 93% of the BLM protests were peaceful (Mansoor 2020, para. 1).

Regarding the 7% that turned violent, it is unclear how many were instigated by police violence or counter-protest/provocateur violence. Moreover, it is certainly problematic to club together all kinds of protests that happened during the pandemic that were not directly related to the pandemic under the provocative category of “riot.” Gerbaudo would perhaps put the farmers’ protest in the category of pandemic riots, like the Black Lives Matter Movement in the US. However, just as Gerbaudo’s categorization does not help us understand the BLM protests, it is equally unproductive to use his model to understand the farmers’ protests.

Many Indian activists, protesters, scholars and social scientists understood the farmers’ protest as a Satyagraha, a Gandhian concept of civil disobedience that demonstrates resistance by holding on to the force of truth (Aravindakshan 2021, para. 3; Ganguly 2021, para. 1; Louis 2020, para. 44; PTI 2021, para. 3). Like the farmers’ protest, non-violence was one of the key concepts in the BLM movement as well, which set it apart from what Gerbaudo calls pandemic “riots.” Protests such as the Farmers’ protest and the BLM have less to do with the pandemic governance than other social issues. For instance, the farmers’ protest employs a mechanism of disobedience while pushing for specific demands while pandemic governance happens to be on its way.

Under normal circumstances, a social protest requires getting out of one’s home and demonstrating resistance in public (or on social media if one has access to it). However, what does “getting out” mean when a pandemic wreaks havoc in the world? Over 100,000 protesting farmers lived in makeshift homes blocking the National Highways connecting Haryana and Delhi for a year (Singh 2021a, para. 2). They lived through the harsh winter of North India, fought the fierce summer, survived the monsoon storms and heavy rain when this fieldwork was in progress (April – June 2021). Though the central government made a feeble attempt to engage with the farmers and hold conversations, the police also used water cannons (Jagga 2020, para. 3). Such state actions as making trenches on the road, using nails, fences, barbed concertina wires, iron lances, and maces mixed with cement to block the roads also blocked the path for negotiations. The state had blocked water connection, toilet facilities, and internet connectivity to force them to return. The NDA government’s IT department censored social media and the legal departments demonized the protesters with “draconian laws.” They were misrepresented as Khalistanis, separatists, or paid protestors (Nigam 2021, 7).

India’s Foreign Ministry slammed the international celebrities who supported the farmers on Twitter (Business Line 2021, para. 1). At the same time, the government rebuked international diplomats for allegedly passing “ill-informed” comments. For instance, the Indian Foreign Ministry summoned the British Commissioner in Delhi following a debate in the UK parliament regarding the farmers’ protest and the Indian government’s response to it (BBC 2021, para 14; Dawn 2020, para. 1). The courts also saw multiple petitions from the civilians to remove the protestors. These petitions were mainly on the right to public convenience as opposed to the right to protest (Chaturvedi 2020, para. 3). However, as shown before, there have also been instances of calling the farmers’ protest a respectable satyagraha, a non-violent method of political resistance introduced by Mahatma Gandhi during India’s struggle for independence, which means holding on to the truth (Aravindakshan 2021, 3; Ganguly 2021, para. 1).

Social movements today, however, manifest in many different forms and media. Protests can be staged through social media posts and collaborative content creation. Online protests too effectively envision alternative futures like the “prophets of the present” (Melucci 1996, 1).3 These movements proclaim a beginning of change – a change that is already present. These changes manifest not only in the virtual world, but in the physical world as well. The changes that the farmers’ protest brought forth are reminiscent of Melucci’s concept of change which is already present in the apparatus of the movement. The farmers’ protest fundamentally changed the physical landscape of the city when they set up camps on the highways. A view of the national highways 24 and 44 (from November 2020 to November 2021) visualized a discordant juxtaposition of two different kinds of lives.

On the one hand, some people were living in huts and tents on the highways, totally oblivious of the pandemic. On the other hand, other people were living in multi-storeyed apartments who meticulously followed the prescribed protocols of the pandemic governance. It showed the onlookers how livelihood during the pandemic reinforced a social divide. When the pandemic protocols necessitated individuals to maintain social distancing, imperatively, the distance was also implied for collective social groups. This social distance accentuated long-standing social differences representing historically persistent social gaps and class differences. As Melucci writes, shedding light on such gaping distance is essential because “keeping open the space for difference is a condition for inventing the present – for allowing society to openly address its fundamental dilemmas and for installing in its present constitution a manageable coexistence of its own tensions” (Melucci 1996, 10). It opens up a scope for the public to reinvestigate the dilemmas that let social distances go unchecked.

Figure 3: Farmers’ makeshift homes in front of Ushay Towers and Parker Residency, Rasoi, Sonipat (May 2021)

The social divide pointed out earlier between the protesters on the highways and the apartment dwellers inevitably raise questions: Who can afford to practice social distancing? Does social distancing convey the same meaning to everybody? The sudden announcement of nationwide lockdown and mandates of social distancing on 24 March 2020 in India were so poorly planned that migrant laborers were stranded in urban slums with little to no scope for social distancing and no modes of transport to travel back home. Over 10 million migrant laborers treaded several hundred kilometers on foot to return to their home states from March to June 2020 (PTI 2020, para. 1). Daily-wage laborers were left with no alternate source of income. With the covid cases rising uncontrollably, the country’s healthcare system was in total collapse. There was a vast precarity and class discrepancy regarding who could afford medical attention and who could not. Considering this backdrop, it is no surprise that the farmers living in camps on the national highway had little concern for the norms of social distancing. Their priority was to consider what would happen once (or if) the pandemic ended, but the farm laws remained. Therefore, it came as a necessity to disregard the apparatus of social distancing in the process of protesting against the farm laws. To this goal, narratives of resistance against pandemic governance were born though the fight was primarily against the farm laws. A study of these narratives of resistance, protest, and coming together shows that though the practice of social distancing is necessary to fight a pandemic, it is also a highly divisive and discriminatory behavior that researchers and activists should, at least, critique, if not resist.

The oral stories born in the farmers’ camps show how people come together in times of crisis and create narratives of resistance. These narratives resisted both the government’s farm laws and the protocols of pandemic governance, especially social distancing. The crisis, in this case, was two-fold, (a) the anxieties of livelihood and (b) survival in the time of a pandemic. Engaging with narratives of both the facets of the crisis, the following sections of the paper explore how resistance manifests in oral and tactile performances. These performances can range from small gatherings in makeshift domestic spaces to large-scale performances on a public stage. In this creative space, an unconventional world is born where new homes are created, and new relationships have been forged that contest the narratives of life on the other side of the social divide.

Contesting the Narratives of Pandemic to Resist the Farm Laws

Protesters construct their rationale for collective action and root their claims politically and morally through collective action frames which Snow and Benford define as an “interpretive scheme that simplifies and condenses the ‘world out there’” (Snow and Benford 1992, 137). Marc W. Steinberg extends on the collective action frame to arrive at a repertoire of discourse. In this repertoire, he reads “an ongoing dialogue” between the powerholders and the challengers. He writes, “when challengers develop a discursive repertoire, they thus seek both to legitimize their claims within the existing ideology of domination and to subvert some of the powerholders’ justifications” (1995, 65). It resonates partly with the Gramscian idea of “counter-hegemony,” which Alan Hunt elaborates in his article “Rights and Social Movements: Counter-Hegemonic Strategies.” As Hunt writes, “the most significant stage in the construction of counter-hegemony comes about with the putting into place of discourses, which whilst still building on the elements of the hegemonic discourses, introduce elements which transcend that discourse” (1990, 314). The protesters further this counter-hegemonic discourse refuting the state’s arguments through oral and performative engagements.

In May 2021, Rakesh Tikait, the leader of the Bharatiya Kisan Union (BKP; Indian Farmers’ Union), announced that the farmers would not go back. His comments hinted at a conspiracy theory. He proclaimed that if the farmers contact Covid-19, the government will be held responsible. According to an April 2021 news caption reported by Capital TV, Tikait said:

The government wants to end the movement with its curfews. But the farmers’ movement can go on until 2024. Under no circumstances, will the farmers end this protest. We will continue the farmers’ protest… The movement will happen on a large scale, without any fear and inhibitions. If the BJP government carries out the clean [India] campaign then the farmers will also carry out a cleansing campaign against the BJP. Protest demonstrations will go on… The government is waiting thinking that the farmers will have to go back during the wheat harvest season. But the farmers will not go back. Because different farmers harvest at different times. The farmers will constantly sit at the protest. The movement will not be affected by the harvest season. (Capital TV, 2021)

Tikait’s comment tells us that the pandemic did not break the farmers’ resolution even after seven months of living on the road. However, it is essential to note that the protests took on a relay format during the harvest and sowing seasons of wheat and rice in April – May 2021. During this time, the farmers kept the protest alive by working in shifts (TNN 2021, para. 3). Every village had some representatives present at the protest site during the harvests when the others went back to harvest their crops. Within one or two weeks, another group arrived to relieve the previous group of its duty so that they could go back for a week to finish their unfinished work if they had any. At any point in time, the camps were never left empty.

Figure 4: Inside a tent in Rasoi, Sonipat (April 2021)

Protest narratives resisting the pandemic protocols had different dynamics of understanding contagion. According to WHO, the Covid-19 virus can attack anybody, and people over 60 or with compromised health conditions are at particularly high risk (WHO, n.d.). However, many farmers at the protest site seemed to believe that the covid-19 is a rich person’s disease. As Mohit, a 35-year-old protester, remarked:

The disease has not entered our camps... A person can be sick even staying at home. They can get a high fever. Someone may damage their heart. The world has always had diseases. Now they say, there's this disease going on. But even earlier, the hospitals did not have enough beds/provisions. Now they say, corona has spread more, there's a lot of disease. But the world was sick earlier too. As the world goes ahead, sick[nesses] will come up too. Is it just about the doctors? We don’t have any fewer doctors. The number of doctors is increasing. A lot of people are studying, earning degrees and becoming doctors… (Sighs) God shows us the world. Sorrow, joy, life, death… everything is in god's hands…4

Mohit’s statement, “the disease has not entered our camps,” dismisses the effects of the pandemic in the farmers’ camps. Nevertheless, he did not completely deny the existence of the virus outside of the protest camps. Moreover, his words betray a strong sense of disappointment in the system. His words elaborate that the covid-19 pandemic was nothing new to him. His uses of irony and satire make one realize that to the farmers, expecting healthcare for something as ubiquitous as covid-19 was preposterous because they never received proper medical attention for anything before! The issue, therefore, was not merely the farm laws anymore. It was a tangled mess of several deep-rooted problems. Mohit’s grievance that his people did not get medical treatments even when the country produced more and more medical practitioners suggests that he had lost faith in the system.

For the same reason, he and his people turned to god and learned to live with the illnesses like any other ups and downs of life. Eulogizing this struggle, Ramanpreet, a 71-year-old farmer, once commented, “Punjabis don't get corona. Even death is afraid of the Punjabis. There has not been any covid here.”5 Therefore, the farmers’ sentiments were not limited merely to fighting for their agricultural rights, but they also extended to the issues of rapidly privatizing healthcare and the collapsing infrastructure of the public healthcare system in India. Consequently, satire, irony, and sarcasm in everyday language became chosen methods of affective outburst.

While some protesters, at least, acknowledged the “reality” of the pandemic, others believed that the pandemic was fake. To them, it was a conspiracy, and the rumored covid-19 virus was a tool for subjugation. Abdul, a 70-year-old man protested:

No, child, the coronavirus is fake. It is for fooling the farmers and breaking their determination. Initially, they blamed the Muslims for spreading the virus. But the virus is not even real. How would there be a corona disease? It comes and goes. What corona? Don’t you get fever or catch cold? Everybody gets flu and fever. They make it corona. They call it corona, but corona does not even exist. There is no such disease in the entirety of Hindustan. These are all their tricks to stop the movement. But our protest will not stop.6

Abdul shifted from talking about subjugating the Muslims to subjugating the farmers. He believed that the rumors about the pandemic were fake. Allegedly, the Indian government devised the rumours about the pandemic with the sole purpose of destroying the traditions of dissent. Though skeptical about the existence of the virus, some farmers, however, believed that the pandemic was real – but only in the world outside. For instance, Sahajpreet, a 30-year-old farmer, said, “we haven't got any such cases of someone getting fever, cold and cough... I don't know how it is spreading in the country... But here, the pandemic did not appear. There were neither any psychological ramifications nor any physical effects.”7

The farmers’ attitude towards the pandemic did not have a monolithic narrative. Leaders and ordinary folks often expressed discordant ideas. For example, Jagdish, an almost 70-year-old farmer, asked, “what is corona[virus] for those who work in the scorching sun every day? It’s [a disease] for those who live their lives cooped up in their houses.”8 Manmohan, a son of a farmer who also works in a pathology laboratory, reported that his laboratory vaccinated every employee before the vaccine reached the common masses. However, he did not take the vaccine because he did not believe that the virus could harm him.9 Though Manmohan had access to the vaccine, it was not accessible to everybody at the protest site at the time. Not only did the government run out of vaccines (Alluri 2021, para. 3), but the majority of protesters did not know how to register online for vaccination, or did not have a smartphone to do so. Though some farmers were skeptical, non-believers, or were radically opposed to the vaccination drive, others did admit the threat of the pandemic was real. For instance, in a previous interview, Tikait, the BKP leader, said, “just as Monsoon comes, the pandemic will also come to Delhi… But let corona come. Even if all its relatives come, we will not stop our protests. We will follow all the guidelines. Now, this protest site is our home. After a lockdown is imposed, we will follow the guidelines but we will still stay here” (Capital TV 2021). Though the farmers turned the highways into their villages, like Tikait said, following pandemic protocols was far from the reality. To the farmers, defying the pandemic regulations was itself a part of their counter-hegemonic repertoire. Making the highways their home, too, was a political statement that challenged the hegemonic norms.

Figure 5: Guru’s Langar, a public langar service outshining KFC at Singhu Border (June 2021)

Building a Home on the Highways

The farmers’ makeshift homes (tents and tractors) in the middle of the highways challenged the traditional understanding of “home” that often presumes the permanence of a house.10 The farmers and laborers imbued the makeshift homes they built over the year with intense feelings of emotion and a sense of belonging, togetherness and solidarity (For more, see Singh 2021b, para. 5). When I asked Mohit and Joginder, two young farmers, how they came to live in the same tent though they never knew each other before, Mohit smiled, “we share a lot of love.”11 Answering the same question, Rohini remarked, “we are all Punjabi; We do not differentiate [our fellow protesters on the basis of] who is from which village.”12 She said that though most of the tents have the name of a village written on their door, they house people coming from different villages. Her tent had men and women from many different villages. Living together for almost a year, the protesters had forged a bond of friendship that very closely resembled that of family. As Rathinder, a Sikh Sardar I met at a tent of the Muslim brotherhood, remarked:

After coming here, it didn't feel like we came from different places. We all got united… There is no difference between us. No one is Muslim, no one is Hindu, no one is Christian amongst us… We all want the same thing. We don't discriminate. Nobody has any prejudice against anyone's choice of food. Nobody has hatred towards anybody, be it Hindu, or Muslim or Christian or Sikh. Nobody cares about that… We have a good relationship. We are all here together.13

As Rathinder explained, the protesters were young and old, men and women from different religious backgrounds. Despite that, they cooked together, ate together, and slept at the same place that they called home. The idea of social distancing did not exist in this environment of protest because by creating an unconventional home, they transceneded public space to enter into more intimate levels of spatiality.

Figure 6: Abdul, a Muslim laborer, and Sahajpreet, a Sikh farmer bonding over narratives of protest at the tent of the Muslim Brotherhood, near Singhu Border (June 2021)

While talking about her new home on the highway, Rohini went back to the very beginning of the protest. She narrated how she left home in the first two months of protest and joined the sit-ins in Chandigarh, Punjab. When their voices were not heard from Punjab, they decided to take their protest to Delhi. The farmers came riding tractors to surround the parliament and make the government listen to their demands. However, they could not reach anywhere close to the parliament because of the resistance they faced from the union government. However, the police or the government could not intimidate them back to their homes. They decided to stay wherever they had reached and make a temporary home when they could not go forward. As she reminisced with a hint of nostalgia, initially, they had to live in small tents. They had brought minimal food with them.

Nevertheless, gradually, when more and more people started coming, they joined forces to make bigger tents. Then they started holding daily langars, i.e., a Sikh community kitchen for serving free meals to people, which continued until farmers went home in November 2021. As Rohini reported, each of these langars served food to hundreds of people every day. Further, some of them used to operate twenty-four hours a day.14

When I asked about the langar service in a Muslim brotherhood tent I visited, Abdul invited me to eat sweet rice at his tent and told me a story. “You know the Rasoi Dhaba,15 right?” he asked. “People come from there to eat here.” Reportedly, people traveled 15 km smiling, “chacha, we want to eat the food that you make with your [own] hands. We don’t want to eat anywhere else.” There used to be a long queue in front of the tent during lunch and dinner times. As Abdul ruminated, “minimum five to six thousand people used to eat here before the paddy sowing season started… Just before you came in, three sardars had their lunch here.”16 Though it was hyperbolic when he said that more than five thousand people used to eat in his tent, the central message that countless people used to eat together in that tent irrespective of their caste and religious identity did not get lost. To add to Abdul’s point, Rahul, a Punjabi Hindu farmer of 30, applauded the Muslim brotherhood:

We have been coming here for six months now, ever since they started the langar. The langar service of the Muslim brotherhood is a huge contribution to our movement. They have been here ever since the movement started. Now you see less people because the farmers have gone back to sow paddy. Come back after a month or two, you will see it full again. This langar has a very good reputation… Now you are eating sweet rice here. But, the chole kulche here was like a “discovery” to us. There is no rival to it. If you come back here in a crowded day, it won’t feel like you are in a tent of the Muslim brotherhood. No, here you will find the Hindu gentlemen, you will find the Sikhs, and you might find some Christians too… You know the phrase, “unity in diversity,” right? You will get that message here. We have a very old relationship with this place. While passing by this tent, our steps automatically slow down.17

Sharing the dining space is one of the strongest stances of togetherness that reifies the bond between people, especially considering that India has a highly stratified social structure where religious differences and caste and class hierarchies bar people from sharing meals (Sherinian 2007, 239). However, it should be noted here that, as per recent trends, Punjab is one of the states where the BJP and its orthodox Hindu nationalism are the least popular. So, it was not surprising to see the growing amity between people following different religious ideologies bonding over food.

As Charles Tilly writes, “When states made demands on their citizens that threatened widely shared collective identities or violated rights attached to those identities, holders of those identities often formed revolutionary coalitions, acquired broad commitment to those coalitions, and resisted immediate suppression” (2006, 173). Following the same logic, farmers and laborers united. Hindus and Sikhs consciously went to Muslim langars and shared the same dining space in public.

However, not everybody who took meals at the langar was a farmer or a laborer. Poor people from the neighborhood often came for free meals. Anybody who passed by was welcomed and offered a meal at the langar. Though langar as a concept holds religious significance in Sikhism, it transcended the religious symbolism and became a cultural symbol demonstrating the significance of the farmers’ existence as anna data18 and their service to the society. At the same time, through the collective experiences of emotions over the langar and associated practices, the protesters built an affective space on the national highways where they felt at home and welcomed everyone with open arms.

Figure 7: Cooking meals in a tent in front of Parker Mall, near Kundli, Sonipat (April 2021)

Conclusion: Resisting the Social Divide/Distancing

Since the farmers built their movement upon a series of non-normative stances, social distancing remained unimaginable in the protest site. The farmers’ protest camps on the borderland between two states (Singhu and Tikri border are two important borderlines between Haryana and Delhi) signify defiance against administrative borders and social divides. A border, by definition is supposed to be a no-man’s-land that divides two sides. Nevertheless, by building homes, albeit makeshift, at the border, the farmers pointed out the need for bridging gaps to promote hybridity. The farmers themselves, as shown before, had done away with social borders between religious and caste identities. However, this flouting of the divide was only possible in the space of protest. It is unclear if they reinstated the borders and differences after they left the protest site when the government repealed the farm laws.

The main point of any protest is to oppose the given structures and raise concerns (Schwartz 1976, 129). It would be risky to judge the farmers’ attitude towards pandemic protocols based on the logics of medical science and national safety, for they were more concerned about the long-term survival of their social class, and rightfully so. The farm laws and pandemic governance were intertwined with each other temporally and logistically. As the farmers understood, the NDA government took advantage of the pandemic restrictions to pass the farm bills hastily and anticipated little to no resistance. By flouting the social distancing mandates and making the roads their home, the farmers raised concerns and also demonstrated an act of bridging gaps. The Singhu border is an urban industrial area lined with industrial buildings and high-rising apartment societies. By erecting a village full of makeshift homes in the middle of this urban space, the farmers unsettled the long-standing urban-rural divide. It made the “high-horsed city-dwellers” cringe because the aesthetics of their urban environment had been trampled by the huts and tents of the farmers and laborers. There were rumors that a mob from Parker Residency had plans of going out with sticks to beat up the farmers and chase them away. Parker Residency is an apartment society 100 meters away from the protest camps at Rasoi (15 km from the Singhu border). The farmers, however, knew nothing about this rumor. I encountered this rumor from a (former) resident of the Parker Residency apartments.

On the other hand, the farmers held their non-violent and peaceful stance following the Gandhian model of satyagraha. They invited the locals to share meals with them. Rohini and her tentmates even asked people to bring containers to carry home extra food for their friends and family.19 The difference in the attitude of the farmers and the apartment-dwellers towards each other made it clear that the social divide observed between the two was porous and structurally frangible. The proximity of the other and the narrowing of the social distance threatened the imaginary divide that the self-proclaimed sophisticated group had established.

Figure 8: An ongoing langar service at the Singhu border (June 2021)

The main rhetorical move adopted by the protesting farmers was to disrupt the order by challenging uncontested norms and long-accepted meanings. By living on the streets, they confronted the arbitrariness of social and spatial mobility and imposed a stasis on it. By flouting pandemic norms, they questioned the arbitrariness and unequal impacts of pandemic governance on the masses. By bringing the home out into the world, they subverted the very meaning of home. Moreover, by constructing a village in the middle of urban space, they altered the city’s meaning and aesthetics.

The farmers’ commitment to satyagraha, i.e., non-violent resistance was one of the qualities of their protest that sustained their movement for a year and ultimately brought them victory (Mohan et al. 2022, para. 6; Srivatsan 2021, para. 1–3). As seen in history, though violence sometimes offers an immediate outcome, violent resistance does not always succeed (Scheidel 2017, 243). As Walter Scheidel writes, there have rarely been any successful peasantry-based revolutions in the recent past (243). The Naxalbari Uprising in India (Phase I: 1967–73) was suppressed within five years. Hundreds of people were killed, and around 20,000 people were imprisoned (Lawoti and Pahari 2009, 208). The Salvadoran peasant uprising in January 1932 was curbed in a matter of days. It resulted in the army massacring the peasants, which is now known as the matanza or “slaughter.” However, non-violent protests like the Gandhian Satyagraha, the model the farmers’ protest was following, show a better and safer success rate.

A social protest’s commitment to non-violence is secured by its performativity (Garlough 2008, 340-41). Performances of protest can manifest in many forms ranging from daily usage of contentious repertoire (See Tilly 1993, 276) to sloganeering to staged performances. As Gencarella and Pezzullo write, the rhetoric and performances of protest have a wide range of concerns, e.g., politics and aesthetics, persuasion and pleasure, activism and art, citizenship and entertainment, etc. (Gencarella and Pezzullo 2010, 1; Garlough 2008, 341). The various concerns of the farmers and laborers found creative expressions in digital and physical media in the form of art, music, and memes throughout the movement. Songs of resistance played a vital role in the repertoire of protest. In February 2021, two Punjabi songs were taken down from YouTube after a legal complaint was lodged by the NDA government (P. Kaur 2021, para. 1). Perhaps looking into such songs of resistance and other performances emerging from the farmers’ movement can open up more possibilities of understanding the repertoire of protest and popular culture during the pandemic.

Notes

1 The farm laws were repealed by both the houses of the parliament after a year-long protest by the farmers of Punjab and Haryana on November 29, 2021. [ Return to the article ]

2 The article is borne out of ethnographic fieldwork (April 2021 – June 2021) carried out at the farmers’ protest camps in Haryana, India. Unfortunately, most of the protesters were temporarily away harvesting wheat and sowing paddy when I did my fieldwork (For more on how the protest continued during this time, see section III, para. 2). For this reason, the pictures I clicked cannot fully represent the size and scale of the protest (Visit the websites https://www.theguardian.com/world/gallery/2020/dec/16/indian-farmers-protests-in-pictures or https://www.gettyimages.com/photos/indian-farmers-protest for a more comprehensive photo album of the farmers’ protest). Though I started with the intention of “collaborative ethnography” (see Lassiter 2005, 84), I could only carry out participant observation and sporadic personal and group interviews because of pandemic restrictions and logistical issues. The interviews quoted in the article have been lightly edited for better readability. While some of the interviews quoted here were taken at the protest camps in Rasoi, others were taken at the Singhu border. The article uses pseudonyms instead of the real names of the interlocutors to protect their privacy. [ Return to the article ]

3 While writing about social movements, Alberto Melucci notes that contemporary movements are “prophets of the present.” What sets them apart, according to him, is the power of the word (Melucci 1996, 1). [ Return to the article ]

4 Mohit, 35 Man, Singhu Border, June 2021, personal interview. [ Return to the article ]

5 Ramanpreet, 71 Man, Singhu Border, June 2021, personal interview. [ Return to the article ]

6 Abdul, 70 Man, Singhu Border, June 2021, group interview. [ Return to the article ]

7 Sahajpreet, 30 Man, Singhu Border, June 2021, personal interview. [ Return to the article ]

8 Jagdish, 70s Man, Rasoi, April 2021, group interview. [ Return to the article ]

9 Manmohan, mid-20s, Rasoi, April 2021, personal interview. [ Return to the article ]

10 There exists a plethora of research on the philosophy of home and homemaking. However, as Shelley Mallet writes in “Understanding Home,” a home is a multidimensional concept, and its multidimensionality makes it difficult to define and operationalize in research (2004, 62). As Ralph and Staehli write, a home exhibits intimately related yet distinct aspects that are variegated as well as overlapping (2011, 517-18). Alison Blunt and Robyn Dowling define home as “a place, a site in which we live” (2006, 2). Nevertheless, they also agree that “a home is also an idea and an imaginary that is imbued with feelings. These may be feelings of belonging, desire and intimacy… but can also be feelings of fear, violence and alienation” (Ibid., 2-3; Blunt and Varley 2004, 3). Put most simply, as Blunt and Dowling would say, a “home is: a place/site, a set of feelings/cultural meanings, and the relations between the two” (2006, 2-3). However, as the protesting farmers in makeshift homes demonstrate, a home invokes a feeling beyond a singular spatial permanence that is often implied by housing. As Ben Rogaly and Susan Thieme point out in the context of makeshift homes of Indian migrant laborers, a home can very well be a spatiotemporal experience of a life lived stretched out and multiplied across space and memory (2012, 2086). A home does not necessarily have to be geographically locatable at all times. It can be a place, an entity, or simply an affective familiarity that one emotionally connects with. [ Return to the article ]

11 Mohit, June 2021. [ Return to the article ]

12 Rohini, late 60s woman, Rasoi, April 2021, personal interview. [ Return to the article ]

13 Rathinder, 55 man, Singhu Border, June 2021, group interview. [ Return to the article ]

14 Rohini, April 2021. [ Return to the article ]

15 Rasoi Dhaba is a moderately expensive restaurant that serves traditional Punjabi and Haryanvi food. [ Return to the article ]

16 Abdul, June 2021. [ Return to the article ]

17 Rahul, 30 Man, Singhu border, June 2021, group interview. [ Return to the article ]

18 In various Indian cultures, farmers are often referred to as anna-data, “the provider of rice/food.” The same term can also mean “god” in Sanskrit and most of the modern Indian languages. It can refer to the master of a servant or the head of a household as well. [ Return to the article ]

19 Rohini, April 2021. [ Return to the article ]

Works Cited

Alluri, Aparna. 2021. “India’s Covid Vaccine Shortage: The Desperate Wait Gets Longer.” BBC News. May 1, 2021. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-56912977. Accessed June 30, 2021.

Aravindakshan, K. 2021. The Gandhian Ideal of Satyagraha Can be Recognised in the Movement against Farm Laws.” The Indian Express. February 9, 2021. https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/farmers-protest-gandhi-satyagraha-7181358/. Accessed June 30, 2021.

BBC. 2021. “India Rebukes UK MPs over Farmers’ Protest Debate.” BBC News. March 9, 2021. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-56330205. Accessed June 30, 2021.

Blunt, Alison and Ann Varley. 2004. “Geographies of Home.” Cultural Geographies 11, no. 1: 3-6. https://doi.org/10.1191/1474474004eu289xx.

Blunt, Alison and Robyn Dowling. 2006. Home. London and New York: Routledge.

Business Line. 2021. “Farmers’ Protest: India Slams International Celebrities’ Comments.” February 3, 2021. https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/news/national/farmers-protest-india-slams-international-celebrities-comments/article33738635.ece. Accessed June 30, 2021.

Capital TV. 2021. “Farmers’ Protest Will Continue in Corona Pandemic Says Rakesh Tikait,” YouTube. April 25, 2021. https://youtu.be/jt9eiBElrzc. Accessed June 30, 2021.

Chaturvedi, Arpan. 2020. “Farmers’ Protest: The right to protest versus Public Inconvenience.” Bloomberg. December 21, 2020. https://www.bloombergquint.com/law-and-policy/farmers-protest-the-right-to-protest-vs-public-inconvenience. Accessed June 30, 2021.

Dawn. 2020. “Trudeau’s Remarks on Farmers’ Protest Prompt Rebuke from India.” December 2, 2020. https://www.dawn.com/news/1593598. Accessed June 30, 2021.

Express News Service. 2020. “Punjab and Haryana Farmer Outfits Mark Dussehra by Burning Effigies of PM, BJP Leaders, Corporates.” The Indian Express. October 25, 2020. https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/ludhiana/punjab-and-haryana-farmer-outfits-mark-dussehra-by-burning-effigies-of-pm-bjp-leaders-corporates-6883206. Accessed January 25, 2022.

Express Web Desk. 2021. “Farmers End Year-Long Protest: A Timeline of How

It Unfolded.” The Indian Express. December 9, 2021. https://indianexpress.com/article/india/one-year-of-farm-laws-timeline-7511961/#:%7E:

text=September%2017%2C%202020%3A%20Ordinance%20is,Rajya%20Sabha%20by%20voice%20vote.&

text=September%2025%2C%202020%3A%20Farmers%20across,Sangharsh%20Coordination%20Committee%20(AIKSCC).

Accessed January 24, 2022.

Ganguly, Sumit. 2021. “Why Indian farmers’ protests are being called a satyagraha – which means embracing the truth.” The Conversation. February 18, 2021. https://theconversation.com/why-indian farmersprotests-are-being-called-a-satyagraha-which-means-embracing-the-truth-155101. Accessed June 30, 2021.

Garlough, Christine Lynn. 2008. "On the Political Uses of Folklore: Performance and Grassroots Feminist Activism in India." The Journal of American Folklore 121, no. 480: 167–91. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20487595.

Gencarella, Stephen Olbrys and Phaedra C. 2010. Pezzullo. Readings on Rhetoric and Performance. USA: Strata Publishing.

Gerbaudo, Paolo. 2020. “The Pandemic Crowd: Protest in the Time of Covid-19.” Journal of International Affairs 73, no. 2: 61–76. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26939966.

Hunt, Alan. 1990. "Rights and Social Movements: Counter-Hegemonic Strategies." Journal of Law and Society 17, no. 3: 309–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/1410156.

Indian Express Online. 2020. “Quixplained: What are the Farm Reform Bills | Farm Bill Explained.” YouTube. September 23, 2020. www.youtube.com/watch?v=4XeTInELA_k&feature=youtu.be. Accessed January 1, 2022.

Jagga, Raakhi. 2020. “The Two Farmers Who First Reached Singhu Border: ‘Changed Clothes Thrice due to Water Cannons.” The Indian Express. December 2, 2020. https://indianexpress.com/article/india/punjab-farmer-protests-singhu-border-water-cannon-7076313/. Accessed June 30, 2021.

Kamal, Neel. 2020. “Farmers’ Protest: Government, Corporate Effigies Burnt across Punjab.” The Times of India. December 5, 2020. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chandigarh/govt-corporate-effigies-burnt-across-punjab/articleshow/79581370.cms. Accessed January 25, 2022.

Kaur, Pawanjot. 2021. “YouTube Removes Two Songs on Farmers’ Protest, Producer Says HQ Cited ‘Govt Intervention’.” The Wire. February, 8, 2021. https://thewire.in/agriculture/youtube-removes-farmers-protest-song-himmat-sandhu. Accessed June 30, 2021.

Kaur, Ravinder. 2021. “How Farmers’ Protest in India Evolved into a Mass Movement that Refuses to Fade.” New Statesman. February 19, 2021. https://www.newstatesman.com/international/2021/02/how-farmers-protest-india-evolved-mass-movement-refuses-fade. Accessed June 30, 2021.

Kiran, Ravi and Jain V Suresh. 2020. “Upholding the farmers’ protest” Letters. EPW 55, no. 49. December 12, 2020 https://www.epw.in/journal/2020/49/letters/upholding-farmers%E2%80%99-protest.html. Accessed June 30, 2021.

Klein, Naomi. 2007. The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. USA: Metropolitan Books.

Lassiter, Luke Eric. 2005. "Collaborative Ethnography and Public Anthropology." Current Anthropology 46, no. 1: 83-106. https://doi.org/10.1086/425658.

Lawoti, Mahendra and Anup Kumar Pahari. 2009. The Maoist Insurgency in Nepal: Revolution in the Twenty-first Century . London: Routledge.

Louis, Prakash. 2020. “Farmers’ Protest: A National Satyagraha.” Countercurrents. December 13, 2020. https://countercurrents.org/2020/12/farmers-protest-a-national-satyagraha. Accessed March 23, 2022.

Mallett, Shelley. 2004. “Understanding Home: A Critical Review of the Literature.” The Sociological Review 52, no. 1: 62–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2004.00442.x.

Mansoor, Sanya. 2020. “93% of Black Lives Matter Protests Have Been Peaceful, New Report Finds.” Time. September 5, 2020. https://time.com/5886348/report-peaceful-protests. Accessed January 25, 2022.

Melucci, Alberto. 1996. Challenging Codes. USA: Cambridge University Press.

Mohan, Deepanshu, et al. 2022. “In Photos: Remembering the Farmers’ Protest, a Triumph of Satyagraha Politics.” The Wire. January 9, 2022. https://thewire.in/agriculture/in-photos-remembering-the-farmers-protest-a-triumph-of-satyagraha-politics. Accessed March 23, 2022.

Monteiro, Stein. 2021. “Farmer Protests in India and the Mobilization of the Online Diaspora on Twitter.” SSRN (May). http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3849515.

Nigam, Shalu. 2021. “A Year of Pandemic, Deadlock, Disaster and Dissent.” SSRN (March). http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3812099.

PTI. 2020. “Over 1 Crore Migrant Labourers Return to Home States on Foot during Mar-Jun: Govt.” The Hindu. September 27, 2020. www.thehindu.com/news/national/over-1-crore-migrant-labourers-return-to-home-states-on-foot-during-mar-jun-govt/article32674884.ece. Accessed January 25, 2022.

PTI. 2021. “Farmers’ Protest: Peaceful ‘Satyagraha of Annadatas’ in National Interest, Says Rahul Gandhi.” Business Today. February 6, 2021. https://www.businesstoday.in/latest/economy-politics/story/farmers-protest-peaceful-satyagraha-of-annadatas-in-national-interest-says-rahul-gandhi-286846-2021-02-06. Accessed March 23, 2022.

Ralph, David and Lynn A. Staeheli. 2011. “Home and Migration: Mobilities, Belongings and Identities.” Geography Compass 5, no. 7: 517–30. https://dro.dur.ac.uk/11542/1/11542.pdf.

Rogaly, Ben, and Susan Thieme. 2012. “Experiencing Space-Time: The Stretched Lifeworlds of Migrant Workers in India.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 44, no. 9: 2086–2100. https://doi.org/10.1068/a44493.

Sahu, S. N. 2020. “The Way Farm Bills Passed in Rajya Sabha Shows Decline in Culture of Legislative Scrutiny.” The Wire. September 21, 2020. https://thewire.in/politics/farm-bills-rajya-sabha-legislative-scrutiny. Accessed January 25, 2022.

Scheidel, Walter. 2017. The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-first Century . Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Schwartz, Michael. 1976. Radical Protest and Social Structure: The Southern Farmers’ Alliance and Cotton Tenancy, 1880-1890 . New York: Academic Press.

Sherinian, Zoe C. 2007. "Musical Style and the Changing Social Identity of Tamil Christians." Ethnomusicology 51, no. 2: 238-80. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20174525.

Singh, Varsha. 2021a. “A Silent yet Spirited Night at Singhu Border.” Media India Group. January 7, 2021. https://mediaindia.eu/politics/a-silent-yet-spirited-night-at-singhu-border/. Accessed June 30, 2021.

Singh, Varsha. 2021b. “Protesting Farmers Singhu Border their Home away from Home.” Media India Group. May 13, 2021. https://mediaindia.eu/politics/protesting-farmers-at-singhu-border/. Accessed June 30, 2021.

Snow, David A., and Robert Benford. 1992. "Master Frames and Cycles of Protest." In Frontiers in Social Movement Theory, edited by Aldon Morris and Carol McClurg Mueller, 133-55. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Srivatsan, KC. 2021. “On 1 Year of Farmers’ Protests, Priyanka Gandhi Talks about ‘Unshakable Satyagraha.’” Hindustan Times. November 26, 2021. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/on-1-year-of-farmers-protests-priyanka-gandhi-talks-about-unshakable-satyagraha-101637909317348.html. Accessed March 23, 2022.

Steinberg, Marc W. 1995. “The Roar of the Crowd: Repertoires of Discourse and Collective Action among the Spitalfields Silk Weavers in Nineteenth-Century London.” Repertoires and Cycles of Collective Action, edited by Mark Traugott, 57-88. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Tilly, Charles. 1993. "Contentious Repertoires in Great Britain, 1758-1834." Social Science History 17, no. 2: 253-80. https://doi.org/10.2307/1171282.

Tilly, Charles. 2006. Regimes and Repertoires. Chicago and London, University of Chicago Press.

TNN. 2021. “Harvest On, Farmers Adopt New Ways to Sustain Stir.” The Times of India. February 22, 2021. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chandigarh/harvest-on-farmers-adopt-new-ways-to-sustain-stir/articleshow/81142042.cms. Accessed June 30, 2021.

Vinayak, A. J. 2021. “More than 84% of Geographical Area in Punjab, Haryana under Agriculture.” The Hindu Business Line. August 16, 2021. www.thehindubusinessline.com/economy/agri-business/more-than-84-of-geographical-area-in-punjab-haryana-under-agriculture/article62160776.ece. Accessed January 25, 2022.

WHO. “Covid-19: Vulnerable and High-Risk Groups.” https://www.who.int/westernpacific/emergencies/covid-19/information/high-risk-groups. Accessed January 25, 2022.