Cultural Analysis, Volume 15.2, 2017

The Role of Costuming in Two Pre-wedding Rituals for Women in Northern Scotland

Abstract: The blackening and the hen party are two pre-wedding rituals for women. The blackening has its roots in a feet washing ceremony, which although once widespread across Scotland is now generally found in rural areas in Northern Scotland. The hen party is a more recent urban phenomenon, enjoying unprecedented popularity. These two rites of passage appear to co-exist happily. Shukla (2005) notes that "successful transitions between life stages are not only socially relevant, they are personally significant milestones, visibly marked by a change in bodily presentation." This paper will explore that "change in bodily presentation" by examining the role costume plays in the blackening and hen-party rituals. There is a huge variety in what the bride and her attendants wear, where the ritual dressing takes place, and at what point during the proceedings. I will show that the purpose of dress and adornment in each of these rituals is varied, from singling out the bride and making a statement, through to establishing group identity. Furthermore, the purposes have changed through time, significantly in the case of the hen party.

____________________

Setting the scene

This paper explores the role played by costume in two pre-wedding rituals practiced by women in Northern Scotland, the blackening and hen party, and how that role has changed since the 1940s. Costuming is just one of many significant elements, such as organization and planning, journeying, games, eating and drinking, and gifting, in the two events that I explored as part of my doctoral research. While any of these would have been equally worthwhile, I focus on costuming, because, of all the elements examined, I believe that this has seen the greatest change in function, particularly in relation to the hen party. Although, the function of costuming has been discussed for life cycle rites of passage, such as the wedding (Charsley 1991; Montemurro 2006; Otnes and Pleck 2003), the role of subverted costuming at other rites of passage is under researched. The blackening ritual itself has largely been ignored by scholars until now, and I introduce the idea of the blackening materials as a type of costuming. In addition, I argue that undress, a feature of both the hen party and blackening, is also a form of costuming.

Before discussing the purpose of costuming in these two pre-wedding rituals, I offer a short description of both. The blackening takes place in the weeks running up to the wedding and is planned secretly by those closest to the bride and groom. Great care is taken, not to alert them to the fact it is happening. The couple knows it will happen but they do not know exactly when. This adds to their anxiety. They might be blackened together or separately. If blackened alone, only her close female friends and relatives generally blacken the bride. If together, the company is mixed. The bride/couple is generally "kidnapped," either from work or home, and often an elaborate scheme has been devised to tempt them out of their home, or to dupe them into believing they are doing something else. There is usually an element of chase as they are expected to try to escape. However, this is just part of the game; they are not expected to succeed. Once caught, they are usually taken to a public space and, to ensure they do not escape, often tied to an improvised pillory, or to each other. They may be given special clothes to wear or may be encouraged to change into old clothes. The blackening proper then begins as the participants begin to pour, throw or squirt litres of the vilest concoctions on top of them, including something sticky such as treacle, and something which sticks, such as feathers. The couple is generally left on display for a while so that passers-by can laugh at their misfortune. The couple then go home, have a shower, and then spend the rest of the evening relaxing and reliving the event with their friends.

The hen party also takes place in the weeks leading up to the wedding. While the bride generally has an input to where and when it will be, as well as who will be attending, there are always a few surprises thrown in that she does not know about, generally designed to embarrass her. The hen party can take place on an evening in a local city, a whole weekend, perhaps in another city in the UK, or a long weekend in a foreign resort. Each is unique and incredible creativity can be shown by some of the bridesmaids who plan the event. In its simplest form it will last one evening and will involve dressing up the bride, sharing a meal, drinking to excess, challenging the bride to lewd dares (generally with strangers), parading the bride to and between venues (pubs and clubs) and attracting attention by making a noise. If the hen party takes place over a longer period it will typically involve all the above but also several daytime activities, such as dance classes, making cocktails or having spa treatments.

The blackening has its roots in an earlier "feet washing" ceremony1 (Young 2016a, 2016b), which, although once widespread across Scotland, is now generally found only in rural areas in Northern Scotland.2 The hen party is a more recent, predominantly urban phenomenon, now enjoying unprecedented popularity. It is practiced throughout Scotland, and indeed throughout the western world, though under slightly different names.3 There is nothing unique about the hen party, as celebrated in Northern Scotland;4 the ritual is homogenous across the UK. While we might expect the blackening to diminish in popularity at the expense of the commodified hen party, there is no evidence to support this. These two rites of passage appear to be able to co-exist happily, with the same women taking part in both. Furthermore, it is not unusual for them to have more than one hen party or blackening.5

However, the rituals are very different. First, the hen party is generally a female only affair (the male equivalent is the stag party), whereas the blackening is celebrated by both men and women, often together. Second, the hen party is ubiquitous; everyone, rural and urban dwellers alike, has a hen party, whereas the blackening is selective. In every village in Northern Scotland there are locals and non-locals (Insiders/Outsiders).6 The blackening is a ritual for locals (Insiders). Non-locals do not get blackened unless they are marrying a local. Related to this is the third difference, the hen party is volitional, the blackening is not. It is done to you. You cannot choose to be blackened. I should add, that while men in Scotland (and elsewhere in Britain) have been blackened, or tarred and feathered in various rituals for decades, it is only in Northern parts of rural Scotland that women are regularly blackened.

The hen (and stag party7), have received some attention from scholars from a variety of disciplines (Hellspong 1988; Tye, Powers 1998; Bennett 2004; Montemurro 2006; Knuts 2007). Costuming is discussed by each of these authors, but not in great depth, and with limited interpretation, and only Bennett looks specifically at the rituals as practiced in Scotland. However, the blackening has been largely ignored, save for recent articles by McEntire (2007), and Young (2016a, 2016b). Although it has been discussed within general works on Scottish traditions such as Gregor (1874, 1881), King (1993) Livingstone (1997) and especially Margaret Bennett (2004), little mention is made of the role of costuming.

Ethnographic data for this study were gathered over a two-year period from women who have attended and organized hen parties and blackenings. The field area was Northern Scotland. I collected around 100 accounts of the blackening and the hen party from women aged between 21 and 93. My contributors came from a wide variety of socio-economic backgrounds (school pupils, students, manual workers, professionals), as well as from a mix of rural and urban backgrounds. I conducted around 50 in-depth interviews lasting around an hour, which were recorded and transcribed, though many other accounts were gathered from casual conversations in the community, for example at bus stops, in shops, at the gym. I attended both a blackening and a hen party. Due to the sensitive nature of some of the information gathered in interviews, particularly about hen parties and initially at the interviewees' request, I decided to anonymize my contributors.8

Roach-Higgins and Eicher (1992, 3) suggest that the term "costume" be reserved "for use in discussions of dress for theatre, folk or other festivals, ceremonies and rituals," since it indicates an "out-of-every-day" activity or social role. However, I would like to describe the type of costuming found at hen parties and blackenings as "liminal costuming," (i.e. costuming associated with a rite of passage) since this type of costuming subverts the normal rules of dress. For example, the removal of clothing, undress, is an important part of "liminal costuming." Dress scholars (Roach-Higgins and Eicher 1992; Shukla 2005; Lynch et al 2007) have focused on the putting on of clothing and other adornments when talking about dress, but the removal of clothing to a state of nudity or semi-nudity, in Western cultures, is just as valid. It also fits with Shukla's definition of body art as "aesthetic modification" of the body. The removal of clothing is the most extreme form of dress that we see at hen/stag parties and blackenings. I would suggest that rather than looking at undress simply from the point of view of deviant behavior, it should also be looked on as a type of "liminal costuming."

Like other areas of pre-wedding ritual, such as playing games, journeying and feasting, normal rules around costuming are not followed during liminal periods. As we will see, costumes worn at hen parties and blackenings subvert normal expectations of dress. In her study of Greek village dress, Linda Welters notes that, "Part of the charm of the special occasion attire was its elegance compared to everyday dress" (Welters 2007, 10). Although dress at hen parties and blackenings is "special occasion attire," it is anything but elegant and it is designed to shock and/or amuse, rather than to charm. Costuming for the life cycle rituals of birth, marriage and death tends to be elegant or sombre, rather than shocking or amusing. There are a couple of exceptions to this. The first is costuming at the Möhippa (Swedish hen party), which Hellspong (1988) tells us involves a masked group of women, dressed as men (with false moustaches and wearing dark clothes), or dressed as little girls with ribbons in their hair, who lead a blindfold young girl in a mock bridal procession. Knuts (2007) brings Hellspong's study up to contemporary times and tells us that the older mock-bride rituals have almost died out but that the hen party is in the ascendance, with sexy outfits being very popular. At the Finnish Poltis9 the bride is dressed up as "provocative sinful" or "ugly, officious or ridiculous" (Åström 1989, 95). Another example is costuming at American bachelor parties, at which, Williams (1994) tells us, men are cross-dressed, feminized, and humiliated. Thurnell-Read (2011) states that one of the ways that the British stag tour experience is embodied is through dress. This is achieved through fancy- and coordinated-dress. Liminal costuming can also be seen at other rites of passage such as hazing (Bronner 2012a, 2012b; Allan and Madden 2008), and calendar customs such as Hallowe'en (McNeill n.d; Santino 1983), and also at festivals and carnivals (Abrahams and Bauman 1978; Driver 1991)

There is also plenty of evidence in the literature for "blacking up" rituals, such as guising, the Mummers Day Parade10 in Padstow, Cornwall, and the (Coco)Nutters Dance11 from Bacup, Lancashire (Buckland 1990). Further evidence is to be found at other "punishment" style rituals, such as rough music (Thompson 1992), tarring and feathering (Irvin 2003; Levy 2011), and at initiation rituals, such as marking the end of an apprenticeship. The apprentice coopers ritual, from Speyside in the north-east of Scotland, is a local example, still taking place today. When the apprentice coopers complete their training they are covered in gunge (pot ale, feathers, etc.), and are then put into a sherry barrel, and are rolled around the cooperage.12 What these rituals share with the blackening is that the community collaborates to put the subject through a trial; in the case of tarring and feathering, it is because they have offended community norms. For hazing and initiation rituals, the initiate is moving from one status to another. What these authors do not suggest is that the blacking up is a form of costuming itself.

Liminal costuming at the hen party and the blackening

"Dress up the hen. It's your duty!" is the cry to the hen party organizers from hen party website, Hen Heaven,13 as part of its accessories sales spiel. So is it a duty, or is it something the majority of women/hen party organizers are naturally inclined to do anyway? Women are said to enjoy dressing up, so it should come as no surprise that all of the 38 hen parties I studied, bar one, included dressing up. Furthermore, at hen parties lasting longer than an evening there were sometimes several changes of clothing for the bride and her hens. Indeed the majority of hen parties (20) involved one change of clothing, four engaged in two changes of clothing, and two had three changes of clothing. For example, for their weekend hen party, HP1 had to provide clothing for a Polka Dot themed evening on the Friday, followed by Burlesque outfits for a Dance class the following day, and then a Nerd theme outfit to go clubbing on the Saturday night. Costuming then, is an extremely important element of the hen party.

On first appearance it would seem that dress, in the conventional sense of the word, may or may not play a part in the blackening ritual. The blackening itself is not volitional, the desires and views of the bride are not taken into consideration, so some brides are given old clothes to change into, some are dressed as parody brides, and yet others are blackened in the clothes they are captured in.14 However, if costuming means changing the appearance of an individual, then surely the concoction of products used, which many of my contributors termed "gunge,"15 could be considered to be some kind of adornment or liminal costuming itself? The blackening materials single the bride out, mark her as "the special one", and generally act a guise (as opposed to disguise). Certainly, she will have trouble removing this guise.

There is generally only one outfit for brides, if they are being dressed up to be blackened, that of parody bride. Brides at hen parties on the other hand can, and do wear all kinds of outfits. Adorning the bride with accessories was generally more common than clothing the bride. The dictionary definition of the term accessory is "items which add interest to and complete an outfit." Props are also a common form of costuming, and rather than its usual definition, I would define it in this context as "a moveable, object separate from clothing and accessories which is used to add to the performance." The most popular accessories were the sash, veil, tiara and L-plates.16

Figure 1. Figure 1 illustrates the difference between these items in the bride's costume. The burlesque basque is the clothing, the sash, veil, and badge are the accessories and the inflatable man (unfixed, unattached) is the prop.

Although not a pre-requisite of a hen party, dressing up is an accepted part of the vast majority of hen parties today. Generally speaking, those who do not dress up do so to set themselves apart, to be different, or to distance themselves from the rest of the society. The bride is the focus of the dressing up, but it is increasingly common for all of the hens to engage in dressing up too. At the blackening only the bride is dressed up, though the blackeners are dressed in protective clothing.

In summary then, all blackenings include "adornment" by blackening materials, however not all brides are dressed in costumes before the blackening "adornment" is added. Although not a pre-requisite for the hen party, dress and adornment is extremely popular with groups of hens.

The purposes of liminal costuming at the hen party and the blackening

What, then, is the purpose of dress and adornment at hen parties and blackenings? When I asked my contributors that question, I discovered, like Simon Bronner (2012a, xvi), that "often influences and consequences exist outside of their awareness." Only the first two purposes were identified by my contributors (emic), the rest were etic. Furthermore, the function depended on the role of the contributor; there were many more functions for the bride, than for her entourage. We will also see that, in some cases, these purposes have changed with time.

The functions of liminal costuming

- To make the bride as filthy as possible

- For fun and amusement

- To ritualize the event

- To single out the bride for attention

- For functionality

- To embarrass the bride

- To communicate messages

- To attract the male/public gaze

- To enable licensed behavior

- To help the group to bond

- To memorialise the event

- To display class identity

- To contrast with the wedding day

To make the bride as filthy as possible/feel as ridiculous as possible

[Leanne] I was in the shower for at least half an hour to an hour, because it took seven washes to get the stuff out of my hair. I wasn't bothered about bits being in my hair [...] I think it almost went worse when I added shampoo to it. It just became like a sticky mess and you think you'd put your head under and it would just rinse off but it didn't. [EI 2013. 073]17

and

[Jenna] You're never so glad to get a shower but [...] you can still smell it for weeks after especially when you're damp. [EI 2013. 076]

In the eyes of the blackeners, the main purpose of applying the gunge is to make the bride look as filthy as possible, and feel as disgusting as possible, for as long as possible, as these two accounts show.

At the hen party, the principal aim of liminal costuming is to make the bride look and feel ridiculous. This in turn gives the group great enjoyment.

For fun and amusement

Jasmine had two hen parties, one in the UK, the other in Australia, where she was living at the time. Here she talks about an amusing incident related to dress at her Australian hen party:

[SY] What did you have to wear?

[Jasmine] [laughter]. It was a dress, like a short summer dress, and then there was a big sash that said, "Miss Eaglebay 2000" because we were staying in this house at Eaglebay. And there was a tiara and I think I had this flyswatter that was the shape of Australia ... But it was quite amusing because we turned up, me dressed like this, and there was a table of American people sitting in the restaurant. And I guess most people would think, "Oh it's a hen party" and this American table [laughter] actually thought that I'd won some beauty contest, and was actually Miss Eaglebay, which was quite funny. Hilarious. [EI 2014.090]

The bride is not always made a mockery of and in some cases her wishes, regarding dress, were taken into consideration, as we can see here:

[Mandy] In the evening we want to dress up a bit. Pam [the bride] is very glammy and glitzy. So we thought there would be a little bit of a theme [sparkly] and we'll all sit down for dinner and that will be the main evening. [EI 2014: 089]

The chief reason for pillorying the bride at a blackening is so her friends, family, and often, the public, can laugh at her, as this account of Clare's second blackening illustrates:

[Clare] They tied us upsides down to a tree in the car park an' left us and they were goin' past us in their cars and jist laughin' and singin'. And we was left there for about half an hour til an hour I think and it was Sunday night and everyone was gaen past, tootin' their horns. [EI 2012: 025]

Dressing up was generally perceived to be an enjoyable activity, or it was seen as amusing. The principal reason, given by my contributors, for dressing up the bride at the hen party and the blackening, was simply for fun and "to have a laugh." Of course the question arises, fun and amusement for whom? There is dressing up and there is dressing up; dressing up to look good, in clothing of one's own choice, is an altogether different proposition to being dressed up in an embarrassing costume with the chief aim of being made to look ridiculous. The bride is frequently dressed up, to amuse and entertain both her inner circle (her entourage), and the outer circle (passersby).

To ritualise the event

Dressing up is a way of ritualising an event, of separating the extraordinary from the mundane. It is a frequent feature of a ritual or rite of passage (van Gennep 1960; Turner 1969; Driver 1991; Leeds-Hurwitz 2002). The principal reason is to mark the occasion as "special". Special clothes are set aside for special occasions. Shukla tells us that "successful transitions between life stages are not only socially relevant, they are personally significant milestones, visibly marked by a change in bodily presentation." This is so that the wearer feels that he/she is taking part in something special or sacred as well as the wearer realizes that she has reached a significant moment in her life. The costume also helps members of the community and the public to recognize this as a significant moment and, while urban living has led to an increasingly individualist society, it was clear during fieldwork that ordinary members of the public still acknowledged that the individual was marking a significant life cycle event. This acknowledgement could be as simple as a smile or a comment such as "good luck," or there could be more verbal interaction with the bride.

To draw attention to the focus of the ritual, the bride-to-be

I observed hen parties in Aberdeen, Edinburgh, and Liverpool. Admittedly, I had a trained eye, but I could spot a hen party, and most notably, the bride to be, from a considerable distance, and this was the intention of the costuming. Of the senses, sight and sound are most commonly employed to draw attention toward the bride, and to the event. You can see and hear them from afar. The tiara and veil, or the deely-boppers, raise the height of the bride and make her stand out from her entourage. The tiara and veil are frequently white or pink, and sparkly. Singling out the bride can also be achieved by the use of color. HP11 wore team T-shirts. The bride's T-shirt was white, the rest were black. Everyone had been told to bring a black skirt/trousers, apart from the bride who was told to wear white.

Figure 2. As figure 2 shows, the bride stands out very clearly through a combination of use of color and accessories. The photo also illustrates how accessories and color are used to single out the other members of the bridal party such as the bridesmaids.

Thurnell-Read (2011), in his study of stag groups, remarked that the status of the stag was often shown by making him wear something distinguishable such as a pink (girly) T-shirt, while everyone else's was black. Having observed groups of stags out in the town, I would say that it is much more difficult to identify the groom within a group of stags; indeed when I approached groups of stags to talk to them I usually had to ask, "Which one is the groom?" The bride, on the other hand, is virtually always instantly identifiable. If we look ahead to dress at the wedding, we see that the groom, his best man and ushers generally wear identical clothing, whereas there can be no disputing who the bride is. Indeed, one of the most important rules for the bridesmaids is not to outshine the bride.

However, the bride does not always have to be dressed up to be identifiable.

[Alison] Well, she was the noisiest and the most visually [...] attractive girl. I just assumed because she was so extrovert and so blatantly sort of ...

[SY] So she didn't have a veil on her head [...] or a sash that said, "Bride"? […]

[Alison] No, no […] but quite soon ... because she sort of caught my eye [laughter] and I said, "Are you the bride?" And she said, "Oh yes." [laughter]

[EI 2013.079]

This contributor travelled by train next to a group of hens. The bride did not have any obvious accessories on to show that she was the bride, yet Alison knew immediately who she was. We can see here that there is something in the behavior, and body language of the bride, that can single her out.

With the blackening, it is the covering of the bride with gunge and the very public manner in which that is done, which draws attention to the bride, rather than her clothing, because perhaps only half of all brides are dressed up at blackenings. Most blackenings are held in a public space, such as a village green, and/or the bride is transported round her community on the back of a truck, accompanied by the noise of tooting horns, shouting and singing, or the clanging of pots and pans. Many people stop to watch and smile, some transported back to their own blackening in years past, others with the uneasy feeling that the blackening lies ahead of them.

For functionality

It would be inappropriate to turn up for a rock climbing class wearing high heels and a short skirt. Conversely, clothing which is practical for a rock climbing class would be inappropriate for a night out in the city. There were numerous accounts of clothing being functional at hen parties. Distinctions were also made between "special" clothes and "normal" clothes. "Normal" clothes were perhaps worn to go shopping or to relax in, while "special" clothes were needed for special activities.

Clothing can dictate where you can and cannot go.

[Freya] But when we went out on the Saturday night after we'd had the Naked Butler, we went to a bar and nightclub and they had specifically said that they didn't accept big, raucous hen parties dressed up, so in some ways it was quite nice that we'd had lots of dressing up, and we'd done our Burlesque class but by that point we all put on our nice clothes [laughter], […]got changed out of our corsets and feather boas and just wore a nice dress out. [EI 2011.014]

Increasingly, venues are prohibiting groups of hens from wearing hen party paraphernalia. Night-clubs have certain standards of dress which customers have to conform to.

A lot of clubs try to promote a certain image, and only allow smartly dressed people, with dress shoes, through the door. No trainers are allowed. Hens dressed up are sometimes treated similarly to those in the queue who are considered too drunk to enter by the bouncers. So clothing, particularly that of hens, is discriminated against and can be at the discretion of the particular bouncers. [Personal Communication, Victoria Mackie, April, 2015]

At the blackening some brides are given the option of changing into old clothes, while others are not. Some blackeners then, give consideration to the functionality of the clothing the bride is wearing, while others disregard it completely. Of course, when it comes to their own dress, they tend to come very well prepared, being careful to wear either protective, or old clothing. The blackening generally ends up becoming a "food fight" and it is impossible to stay clean. The boiler suit is a very popular form of protective clothing worn at blackenings, both by males and females. There are the traditional dark blue boiler suits worn by farmers and mechanics, as well as the boiler suit commonly worn by those working in the oil industry, which often has a reflective stripe at the ankle. Sturdy work boots or wellington boots are the usual footwear.

To embarrass the bride

While many would argue that it is not socially acceptable under any circumstances to walk along Princes Street, Edinburgh, on a Saturday afternoon clutching a large, inflatable penis, it is nonetheless still not against the law to do so,18 and many brides are expected to do just that. There can be no other reason for doing so other than to cause the bride embarrassment. It is typical of behavior during liminal periods. Different behavior is accepted and indeed expected in the day-time economy, compared with the night-time economy, when virtually anything goes. The example given is a case in point. While it might still be embarrassing for the bride to carry the prop in question through the city at 1 a.m., it is unlikely to draw any criticism or cause much offence. Indeed the behavior in the night-time economy is generally so excessive anyway, that hen party behavior has to be super-excessive to cause offence. The inflatable penis carried by a scantily dressed bride to be in the day-time economy however, with its expectation of moderation, caution, sensibleness, is a different prospect altogether. It is designed to shock and to explode accepted norms.

Jasmine talks about the embarrassment she felt when required to do a dare requiring her to approach strangers asking them to suck sweets which were sewn onto a T-shirt she was wearing:

[Jasmine] […] they did make me wear a T-shirt that had sweets sewn onto it and so you can imagine what had to [happen]... to get people to eat sweets off this T-shirt.

[SY] "People" being strange men.

[Jasmine] Yeah, yeah. Which was a bit grim I have to say. [EI 2014: 090]

Indeed, ritually dressing the bride was often associated with playing a game, with clothing and accessories being "punishments" for getting a question wrong, as happened at Jasmine's sister's hen party dinner:

[Jasmine] The first forfeit was quite early on I think. […]So there was things like she had to ask the waiter for a kiss or something ... And then if she did it she got something to wear. So then she got something like the sash. [EI 2014: 090]

In the end the bride was dressed in a sash, veil, garter and pink feather boa.

What about the blackening? In a culture obsessed with cleanliness and perfection, covering a young woman from head to foot in a vile concoction of foodstuffs and other products in the day-time economy, on a village green, a place normally concerned with wholesome community events and families, is designed to embarrass. As the person who is central to the ritual, it is generally the bride who is embarrassed in these situations, rather than those who are putting her through the ritual.

To communicate messages

In the 1970s and 80s on the bride's last day at work before her wedding, it was common for her colleagues to dress her in a home-made coat/dress decorated with paper flowers. Onto this were pinned messages, written by her colleagues. These messages were lewd in nature, frequently alluding to sex, such as the example below from Bennett (2004, 133):

Long and thin goes too far in

And doesn't please the ladies

Short and thick does the trick

And manufactures babies.

Forty years later sex is no longer a mystery for the majority of Scottish women about to get married. Most, in fact, have been living with their partner for some time (Charsley 1991; Bennett 2004). Indeed, apart from one bride married in 2000,19 all the brides interviewed who married in or after the 1990s lived together before marriage. Written messages are still a feature of hen party costumes, but they are now mass-produced and no longer personalized. The hand written rhyme, such as the one above, of forty years ago is today's slogan on a T-shirt which reads, "Horny Hen" or "Hot Hens" (see figure 3). Cullum-Swan and Manning (1994, 423) look at how the T-shirt is used to carry messages.

Figure 3.

They describe this type of text as "floating epithets such as statements emblazoned on the front of shirts referring to a putative self or identity, usually vulgar, crude, attention seeking or all three." They also suggest that "the self becomes increasingly lodged in public displays of claimed statuses, imagined positions, missing or desired feelings, and the ever-present absent consumable, other selves" (Cullum-Swan and Manning, 1994, 429), and "they display what one is not, and may call out for validation of one's absent desires" (ibid. 431).

Costume is seldom used to communicate messages at a blackening. Occasionally a banner with the words "Jenny's blackening" or "Jenny's getting married," will be attached to the vehicle the bride is being transported in, but I did not come across any instances in which written messages were placed on the bride's costume.

To attract the male/public gaze

Costuming is undoubtedly used to attract the male gaze at the hen party. For example, a T-shirt with two fried eggs strategically placed over the breasts. The eye is drawn to the image, and therefore to the breasts. When Sarah Adams wore uli, a form of Nigerian body art she noted, "it was one of the few times when in Nigeria I felt I had a degree of control not over whether people looked at me but how people looked at me, where they looked, and focused their attention" (Adams 2007, 116). Many of the costumes worn by groups of hens are highly sexualized and therefore likely to attract the male gaze.

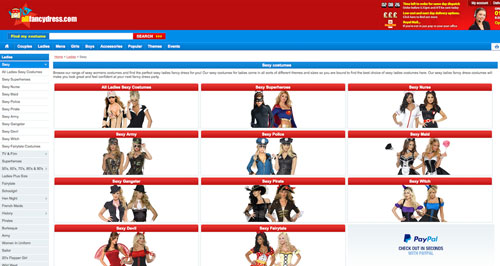

Figure 4. The screenshot below shows the variety of costumes available from the "hen party costumes" section of the website, Allfancydress.com. Categories are Sexy, TV and film, superheroes, 50s, 60s, 70s, 80s, and 90s, fairytale, schoolgirl, history, French maids, pirates, Burlesque, Army, women in uniform, sailor, 20s flapper, wild west, gangsters, clown, popstar, nuns and Hawaiian. In each section, around a half of the costumes are sexualized, with names such as "Sexy Nurse Costume", "Constable Cutie Costume" and "Combat Chick Costume."

One of the iconic symbols of the hen party is the phallus. There are accessories and props of all sorts associated with the phallus, (see figure 5) for example, willy shot glasses, willy whistles, willy deely-boppers, willy chocolates, and the best sellers, willy straws, which, as this interviewee noted, no self-respecting hen party should be without: "you can't have a hen night without willy straws" [EI 2013, 083].

Figure 5.

As to why women at hen parties use accessories and props with objects in the shape of the phallus, such as deely-boppers, willy straws etc., reasons given during fieldwork include "because it's amusing", "because that is what is available in the merchandise," and also "because it has become synonymous with hen parties." Tye and Powers, who looked at stagette parties in Atlantic Canada, think there are deeper reasons for this obsession with the phallic symbol: "At the stagette, young women play with their own sexual objectification through symbolic reversal" (Tye and Powers 1998, 555). They argue that it is normally women, and not men, who are usually conceptualized by their body parts. At the stagette party this is inverted: "The threatening and culturally powerful phallus is deconstructed as benign and socially playful" (ibid 1998, 555). Once again, costumes are being used to explode conventional gender stereotypes.

Attracting the male gaze is not a part of the blackening, though attracting the public gaze is. However, although common, it is not even a vital part of the ritual. I have many accounts of blackenings being held on farms, with no contact with the public at all.

To enable licensed behavior

Does wearing a T-shirt bearing the slogan "Hot Tits Really Squeezy" invite male strangers to see if it is true? The answer is probably "yes", no doubt aided by copious amounts of alcohol to loosen inhibitions. And does wearing that same T-shirt make the wearer herself feel "hot"? The answer to that is "possibly." She may be someone at ease with her sexuality, or she may be at ease with her sexuality at that moment with the aid of alcohol and the sense of occasion. Indeed, various writers have described rituals such as these as performative or theatrical (Abrahams and Bauman 1978; Driver 1991; Schechner 1993; Leeds-Hurwitz 2002). There are similarities here with festivals and carnival. Richard Schechner describes the street as "a stage:"

When people go into the streets, en masse, they are celebrating life's fertile possibilities. ..... They put on masks and costumes, erect and wave banners, and construct effigies not merely to disguise or embellish their ordinary selves, or to flaunt the outrageous, but also to act out the multiplicity each human life is. Acting out forbidden themes is risky so people don masks and costumes. They protest, often by means of farce and parody, against what is oppressive, ridiculous, and outrageous......Such playing challenges official culture's claims to authority, stability, sobriety, immutability, and immortality. (Schechner 1993, 46)

Returning to the bride, and how she feels once dressed and adorned, she may feel anything but "hot," yet she must play on. Dress may be volitional for all except the bride. She may be instructed to dress in a particular costume, wear accessories and carry props. It may be the last thing she wants to do, but do it she must:

[Pam] She'll probably get the tat because she'll want to dress everyone up and parade us around. I think if that happens, that happens […]In my head I don't want it but in reality it probably will.

[SY] But you'll go with it?

[Pam] And I'll go with it. Because I'd just tick it off and leave it somewhere. [laughter]

[SY] So it's better to be a sport than it is ...

[Pam] Yes, than to be the grumpy one.

[SY] ... to be a party pooper. [EI 2013. 086]

In this account, Pam is talking about how her desire not to be dressed up in all the hen party paraphernalia is likely to be ignored by her sister, who is her bridesmaid. Adam and Galinsky (2012) have done some interesting work on what they term "enclothed cognition." They discovered that not only does what you wear change the way other people see you, it also changes the way you see yourself, and the way you think. Their results showed that the symbolic meaning of the clothing you wear, together with the psychological experience of wearing that clothing, can result in changes in your behavior. The clothing acts as a constant reminder of what it represents. Clothes, then, have powers over your mind. In their study of Red Hat Society (RHS) women in the US,20 Lynch, Radina, and Stalp (Lynch, Radina et al. 2007) show that being part of a female only group and wearing the red hats emboldened the members and enabled them to behave in a licensed way. Several contributors stated that they had increased confidence, and felt they could behave a bit wilder. In so doing this challenged normative views on how older women should dress and behave in public spaces. Yet other contributors mentioned the hedonistic attention they received when wearing the red hats, especially from men. What was particularly interesting in this study was that the women associated wearing hats in public with when they were young adults, a time when they were "following rules, being proper, and in many cases dressing up and going to church" (ibid. 2007, 152). Subverting the dress rules they learnt as young women added to the fun of wearing their ostentatious hats.

The role of the bride at a blackening, once she has attempted to escape and been recaptured, is generally very passive. Once she has been blackened she is generally displayed, but does not engage in any form of excessive behavior. Following the blackening there can be some drinking and this has certainly increased over the past two decades, but not usually of the intensity seen at hen and stag parties.

To help with bonding

Dress also enhances the bonding experience. One of the women in the RHS, mentioned above, noted, "When everybody has on the red hat, then you don't feel singled out" (Lynch, Radina and Stalp, 2007, 150). None of the literature specifically on hen parties shows a connection between dress and adornment, and bonding, yet it is undoubtedly a contributing factor. Cullum-Swan and Manning (1994, 421) in their paper on the T-shirt state that it "conveys representations that signal or communicate membership in a group, work place or collectivity," and Thurnell-Read, (2012, 260) talking about the stag tour, states:

Constructing a shared group identity was an important aspect of creating a successful stag tour weekend for participants. The use of matching clothing such as group tour t-shirts or polo shirts emblazoned with a group logo and team motto were a common means of instilling a collective identity.

Twenty women walking down the main street together dressed in virtually identical Burlesque outfits has the effect of uniting the group. Team T-shirts, favored by both hen and stag parties (more so by the latter, who generally show less enthusiasm for dressing up) have become commonplace.

Friendship and solidarity are a feature of hen parties and blackenings, indeed, Pitaoullis (2005, 18) states that bachelor and bachelorette parties are rituals "in which friendship is emphasized." She goes as far as to say that the principal function of the bachelorette party is to ensure that early adult friendships are strengthened and maintained into married life.

At the blackening the bride is "adorned" with gunge, and although she will be the most filthy, all those taking part will also become adorned with the gunge. They are therefore united in the act of ritually dirtying the bride.

To memorialize the event

One way of memorializing the hen party (as well as taking photographs or videos and putting them on Facebook or YouTube) is to retain clothing, accessories and props as keepsakes. Looking at, touching and smelling memorabilia can all bring the event back. The designer T-shirt is a case in point. Cullum-Swan and Manning (1994) tell us that the T-shirt can have a rich association with the past. On the other hand there is evidence on websites such as gumtree.com for clothing, accessories and props (mainly the cheaper, mass produced merchandise) being resold. As the contemporary hen party has only been going in this form from the early 2000s it is too early to show the longevity of the memorabilia from that event.

In stark contrast to this is the clothing used at a blackening. Whether the bride is given old clothes to wear, is dressed as a parody bride, or dressed in her own clothes, all can be considered liminal costumes. What makes them differ from the costuming at hen parties is that they are considered disposable costumes. Whatever is worn is almost always thrown in the bin as it is deemed unsalvageable. I came across one exception to this rule during my research. Evelyn carefully washed and preserved her veil and over-sized nightdress. When I asked why she did so, she replied:

You know, I've no idea! I just did it. I guess for sentimental reasons. And I think I was curious to see if it washed. Which it absolutely did. Also, being a canny Scot, maybe I was thinking I could use it for a blackening in the future! (Personal communication, email, 6/8/15)

However, this is the exception, as these two excerpts illustrate:

[Leanne] What I do know is that none of the clothes we were wearing ever were worn again. [laughter] We blasted them with water ... to try and get a lot of it off and gave up and chucked them in the bin. [EI 2013.073]

and

[Jackie] And then I remember going in to Mum and Dad's shower and takin' a plastic bag through and just puttin' all my clothes in. So I went home with no underwear on. [laughter] So I obviously had my clothes that I took off but I had to take my underwear off because it was just black.

[SY] Disgusting.

[Jackie] Yeah, so I just took everything off, put it in a bag and bunged it in the bin. [EI 2014.002]

I got a sense that the dumping of the filthy clothes into the bin was quite ceremonial in nature. It was a significant act. A sign that the ritual was completed, the filth was washed away, the bride now ready for the wedding. The clothes will never be worn again, and here we find parallels with the wedding gown. It too is usually never worn again, though for different reasons. And it is kept, often with great care, wrapped in tissue paper, and stored in a special place. Sometimes it is handed down as an heirloom. The act of throwing away then, is the symbol of a past life and its accompanying single status; the act of keeping, is the symbol of a future life and status as a married person. You hope to keep your wedding gown, like your marriage, for the rest of your life.

To display class identity/membership of a group

While it may not always be a conscious function of costuming at a hen party to display class identity, it inevitably does. Several of my contributors mentioned that they would not be wearing anything "tacky" at their hen party. "Tacky" is defined here by one contributor:

[Anna] I think my vision in my head of "tack" is the tiara with a veil, and an L-plate sign and maybe a blow up man or kind of, yeah something along those lines would be what I interpreted as "tacky". [EI 2012.023]

This was generally the response of university-educated women, in well-paid jobs. By distancing themselves from the mass-produced, stereotypical hen party costume and accessories they are distancing themselves from the masses.

It cannot be said that the blackening ritual is attached to a particular social class, but it can be said that it is a ritual for locals (Insiders), rather than non-locals (Outsiders). The fact that they get blackened shows that they belong to a particular community, and it is, at the same time, a sign to non-locals that, although they live there, they are not "true locals."

To contrast with the wedding day

Could the bride possibly look worse than she does at her blackening, covered from head to foot in baked beans, yogurt, left-over chicken curry, raw eggs, flour, feathers, treacle, and to top it all off, cow manure? Contrast this with the wedding day, when she is dressed in a gorgeous white gown, at her most beautiful, painted, polished and perfumed to perfection, as illustrated in figure 6.

Figure 6.

Or how about at the hen party, when she looks ridiculously dressed in a pink Smurf outfit with a white tutu? Or when she looks like a "lady of the night" in a nurse's uniform with stockings and suspender belt. Contrast this with the wedding day, when she generally behaves in a controlled manner and is dignified, demure and debonair. Describing the power of the bride figure Charsley (1991, 194) notes in Rites of Marrying:

A bride appropriately dressed and on her wedding day becomes the embodiment of a powerful symbol in the culture, a source of interest, attraction and often emotion even to people who do not know her at all.

The difference is intentional. It's the difference between the sacred and the profane, the wedding ritual and the pre-wedding ritual.

Changes with time

We have seen that costuming has many different functions at the blackening and the hen party, with some, such as memorializing the event or group bonding, being more important at the hen party, than at the blackening. But have these functions changed in the period covered by my fieldwork, the 1940s to present day? By examining closely just one aspect of hen parties and blackenings, the role of costuming, over a period of several generations, it has been possible to show that those changes reflect changes in the role of women in society as a whole. Ethnologists are in prime position to record these changes and make sense of them. As James Porter (1999: 11-12) tells us:

Ethnology deals with traditional culture in the widest sense, and focuses on explaining not only tradition but also change, since the one cannot be understood without the other.

The primary role of costuming, we have seen, is for fun and amusement, and at first glance this has not changed. The blackening and the hen party have always been about having fun. However, on closer examination it appears that where one fun item of clothing for dressing the bride up in, or one or two products to the blacken the bride with, would have been sufficient for the previous generation, this is no longer the case. We are "lovers of novelty" (Hayward and Hobbs 2007, 444), constantly demanding the new and the novel in all areas of life, from holidays, to home furnishings, to gadgets, to fashion and, as we see in this study, to costuming. This is not always understood by women of previous generations, who generally speaking, felt that the behavior of women at both rituals is now "over the top," with costuming one aspect of the hen party mentioned as being a part of that excess:

[Lexi] I really cannot understand brides who spend a lot of money going abroad, Barcelona, and spending money and getting outfits to match and all the rest of it when there is so much expense involved in a wedding. [EI 2012: 031]

The brides and hens, of course, do not see it like that. They are products of a post-modern society (Burrows and Marsh 1992; Urry 2002; Bryman 2004; Skeggs 2004; Winlow and Hall 2006), which in Northern Scotland, has happily cast off the oppressive cloak of Calvinism, and embraced hedonism and sensual enjoyment with gusto. One of the questions I sought to answer during my research was whether there was any sign that the blackening was dying out in favor of the hen party, which has enjoyed an almost meteoric rise in popularity since 2000 (Eldridge and Roberts 2008; Eldridge 2009). I discovered that, rather than giving one up, it is common to celebrate both rituals these days. This also points to what Slosar terms a "culture of excess" (Slosar 2005); it would have been inconceivable in times of hardship to waste good clothing in the way it is wasted at a blackening, and to spend money, often on multiple costumes and accessories, in times of austerity would have been unthinkable.

Changes have not just occurred with hen party costuming; the blackening has also been affected by Slosar's culture of excess. While there has been little change in whether women are dressed up as parody brides at a blackening or not, what has changed enormously is the make up of the "gunge" that is used to guise them. Traditionally, only one, or perhaps two products, together with water, was used in the blackening, and its precursor, the feet-washing.21 Nowadays, however, virtually anything goes, though some care is usually taken to avoid including harmful substances. Pointing to a photograph of her own feet-washing/blackening in the 1940s, Millie explained to me how shocked she was at the combination of products used to blacken her granddaughter:

[Millie] But you can see all that stuff that we've on there, it washed off easily. But they [granddaughter and grandson-in-law] were absolutely caked. If you'd put them into an oven [laughter] they would have...

[Millie & SY] Baked. [EI 2013: 074]

Two of the functions of costuming at the hen party and blackening, to embarrass the bride and to enable licensed behavior, have always been a part of both rituals, however what is acceptable now is very different to what was acceptable in the past. The women I interviewed, who were married between the 1940s and 1980s, would have been utterly horrified if they had been made to dress like a prostitute, or wear a pair of willy deely-boppers, at their hen party. Nowadays, this is both accepted and expected at many hen parties, and we have seen how clothing can help the wearer to feel differently about herself (Adam and Galinsky 2012), and how this in turn can enable licensed behavior. There is a much greater acceptance nowadays of showing bare flesh, or even partial nudity. Men have had to cope with being stripped naked or semi naked at stag parties and blackenings for many years, but it is only in the past twenty years or so that we are seeing similar behavior for women.22Women have increasingly become the victims of blackeners who want to cause them maximum humiliation by removing some of their clothing:

[Tanya] I remember [my daughter] and [my son-in-law]… and they were taken... [my] poor [daughter] just had on her pants and a bra. And they tied them to the fountain outside the [pub] [EI 2013. 087]

Another contributor recalls the scene from the shop she owned:

[Dana] Some of the youngsters go a little bit over the top. When we were in the shop; right opposite the shop was the monument for the village and the amount of youngsters we have seen tied up there and left with not much clothes on I'll tell you. [laughter]

[SY] So that wasn't typical of your day at all?

[Dana] Oh, no. No, no Sheila. [EI 2013: 081]

Lexi talks about the ways some groups of hens behave in public spaces, such as on trains:

[Lexi] But they are quite noisy and loud. And I do feel that some of the lack of clothing that they wear, the brides...it's not very demure for a bride-to-be and I think...but I suppose it's general now [...], [they should] be a bit more civilized. [EI 2012. 031]

Scottish society, it seems, is becoming more accepting of states of undress, exploding traditional gender stereotypes where women, as this excerpt implies, are expected to dress in a modest, demure, civilized way. Barnard, in his work on fashion and visual culture, states that women are using accessories and dress to challenge and resist dominant theories of femininity: "They are constructing their own versions of femininity and class identity from the styles that are available" (Barnard 2007, 103).

Singling out the bride so that she is noticed and attracting the male/public gaze goes hand in hand. One of the ways that costuming does this is through the messages it communicates on clothing. The very public nature of those messages can be contrasted with the more personal, and less visible rhymes and messages pinned to the bride's dress at Pay Off Day23 when she left her job in the factory or office in the 1950s and 1960s (Dyer 1970; Monger 1971; Monger 1975; Beck; 1988; Bennett 2004).

One aspect of liminal costuming that is totally new for the hen party is functional costuming. This has come about because of the growth in Casual Leisure,24 such as classes in Burlesque Dancing, Rock Climbing, or relaxing by a swimming pool. Each of these activities requires different clothing, and not just for the bride; the whole group will be dressed up. Contrast this with the past when the bride would be the only dressed up, and only in one costume, that of parody bride. The hen party used to be a simple evening out, perhaps with a meal, then on to the pub for a few drinks. Nowadays, it is a highly sophisticated ritual, micro-managed to the last detail, and costuming plays a huge part in that. On the other hand, costuming, in the form of applying blackening material to the bride, has always been part of the blackening, and its predecessor, the feet-washing.

Although we might think of "female bonding" as a relatively new concept, one that has arisen as women have started to claim their own space in the night-time leisure economy, Virginia Smith tells us that rituals which encouraged group bonding have been common for centuries:

Betrothal and marriage ceremonies were more festive occasions: the worldwide rituals of preparatory purification, grooming, bathing, and dressing up of the bride and groom were yet another time of extensive group bonding, when every effort was made to bring about good luck, and expel evil influences (Smith 2007, 34).

What has changed is the type of social situation that women find themselves in with other women. Prior to the 1960s women had to give up work when they got married. Once they had children they were very much tied to house and home in the role of housewife and mother (Montemurro 2006; Abrams and Fleming 2010). Abrams and Fleming refer to this as the "strain of containment:"

And for women who were often tied to their homes by the routines of cooking and the care of infants, the Scottish habit of "windaehinging", where women talked to one another from the vantage points of open tenement windows by leaning on the ledges with their head outside, was a particular way of coping with the strain of containment. (Abrams and Fleming 2010, 52)

Their contact with other women would mainly have been during the day, as they went about their normal daily tasks. Abrams and Fleming, note that "the support network operated by women in such working-class communities could offset domestic drudgery" (Abrams and Fleming 2010, 51/52). Prior to the 1960s women did not generally meet up with other women to socialize in the evenings or at weekends. In general, women did not drink, nor did they go into pubs, as this excerpt from an interview with Sally, who got married in 1949, shows:

[SY] What about drinking. Would you ever have ...

[Sally] Oh no, never. Never. Never.[...] I would have been expelled from home I think if I had ever gone in drinking.

[SY] So when you were a young woman, women just didn't go into pubs?

[Sally] No. No, I can honestly say I never was in a pub drinking. That's not a boast, it was just not done. [EI 2013.077]

All that changed with the development of the leisure night-time economy in Britain in the 1980s when there was a deliberate move by the government to rejuvenate British city centres and to try to create more of a café type culture in Britain (Hobbs 2005; Measham and Brain 2005). There was a recommodification of alcohol and a major overhaul in the design of drinking spaces by the drinks industry to attract young people, and women in particular, as they were regarded as an as yet untapped resource. The introduction of clubs and themed bars saw a move from "spit and sawdust" to "chrome and cocktails" (Measham and Brain 2005, 267).

Conclusions

Attitudes towards liminal costuming at the hen party and the blackening are quite different. Women have embraced liminal costuming at hen parties with gusto, with many hen parties having multiple changes of costume. Growth in the popularity of liminal costuming is particularly noticeable in the past decade; before that only the bride was dressed up. However, it is now common for the whole group to dress up, although a distinction is usually made between the dress of the bride and the rest of the group. At the blackening the bride will occasionally be dressed as a parody bride, but costuming at the blackening depends on the adornment of the bride with gunge, which, I argue, is a form of liminal costuming in itself. The rest of the group generally dress in clothing that will protect them from the gunge that they throw on the bride. At the hen party there are a whole range of purposes for liminal costuming, including dressing the bride to amuse the group, ritualizing the occasion, drawing attention to the bride, and embarrassing her. This is in contrast to the purpose of the rest of the group dressing up, which is primarily for fun, and for group bonding. At the blackening, there are fewer functions for liminal costuming. For the blackeners, the most important function is to make the bride as filthy as possible, and to protect themselves, as much as possible from getting dirty. Ritual embarrassment is also important, and although it may not be obvious to the group, it is also about group bonding. It was telling that, for all it is dreaded, one of my contributors told me that people who were not blackened "might have felt a bit disappointed." 25When pressed further about this, she said that they "would have missed out." There was clearly some kudos in being able to say, as my contributor put it, "Yeah, I was [blackened]."26

We have seen that the changes in the function of liminal costuming, at the hen party and the blackening, reflect wider changes in the social life of women in Northern Scotland. Yet despite these changes, the hen party and the blackening remain strongly-rooted, crucial rites of passage for most women. The bride-to-be, covered from head to foot in gunge, or wearing a "Horny Hen" T-shirt, becomes transformed into a vision of loveliness as a bride on her wedding day.

Notes

1The blackening has evolved from an earlier Scottish ritual called the feet-washing, the earliest account of which is in the early 17th century (Burt 1755). There is uncertainty surrounding just when it began, but it probably started as a solemn washing ritual for both men and women on the eve of their wedding, which was usually in the winter months when the demands of the sea and the land were fewer. By the early 19th century the accounts tell of a blackening of the feet and legs using soot from the chimney. A little later, there is evidence that it had developed into a kind of a game, with the feet and legs being alternately blackened and washed, and then by the end of the 19th century early 20th century escape, capture and pillorying had become part of the ritual. In order for this to happen the ritual had to move out of doors. The move out of doors appears to have coincided with a change in wedding practices, with more people marrying in the summer months. Contributors married prior to the 1970s generally referred to the blackening as the feet-washing. Those married in the 1970s and 1980s use both terms interchangeably and the current generation tend to use only the blackening. It is probable then, that a change in the form of the ritual led to a change in name. [ Return to the article ]

2The reasons for why the blackening is confined to Northern Scotland remain unclear. [ Return to the article ]

3For example, bachelorette or stagette party in the USA and Canada, or hens' party in Australia and New Zealand. [ Return to the article ]

4Save perhaps for a predeliction for "tartanry," particularly if the group is travelling out of Scotland. [ Return to the article ]

5For example, one of my contributors was blackened on two separate occasions by two different friendship groups, and another had two hen parties, and a pre-hen party. [ Return to the article ]

6See MacLeod and Payne's (1994) fascinating insight into Insider/Outsider culture in the community of Coigach, NW Scotland. [ Return to the article ]

7Pre-wedding ritual for men very similar to a hen party but perhaps containing more competitive activities, such as quad biking, paintballing etc. [ Return to the article ]

8For instance, a bride talking about not wanting to invite her mother-in-law, or a bridesmaid complaining about the cost of the hen party. [ Return to the article ]

9A contemporary version of the ritual known as the Polterabend. [ Return to the article ]

10http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b06yr6vh A programme about a black film maker, Michael Jenkins, making a documentary about Mummers Day, formerly known as Darkie Day. [ Return to the article ]

11The Bacup Coconutters are men with blackened faces, dressed in skirts, who perform the Coconut Dance at Easter in Bacup, Lancashire. [ Return to the article ]

12https://scotchwhisky.com/video/magazine/9143/the-blackening-at-speyside-cooperage/ [ Return to the article ]

13http://shop.henheaven.co.uk [ Return to the article ]

14It is difficult to estimate the number of brides who are dressed up for their blackening. More work needs to be done to assess this; as a very rough estimate it may be around half. [ Return to the article ]

15This was a term used by several interviewees to describe the concoction thrown over them. [ Return to the article ]

16Learner Plates placed on a car for those learning to drive. L-plates were introduced to the UK in 1935. They were initially used at hen parties to suggest that the bride was a novice to sexual intercourse. [ Return to the article ]

17All the interviews from which excerpts are taken are kept in the digital archive of the Elphinstone Institute, University of Aberdeen. [ Return to the article ]

18Unless a member of the public directly complains to the Police, in which case the Police would have to remove it from the bride. [ Return to the article ]

19The bride described her situation as "unusually traditional." [ Return to the article ]

20The RHS was established in the late 1970s by Sue Ellen Cooper who used dress (ostentatious red hats) to empower post-menopausal women who felt marginalized and stigmatized by society simply because they were aging. The women held lunches in public places and felt empowered and emboldened when they got together and wore their red hats. [ Return to the article ]

21See endnote 1. [ Return to the article ]

22I have not personally heard of a woman being stripped naked at a blackening, but stripped down to underwear is not uncommon. [ Return to the article ]

23Pay Off Day was the final day at work for women before they got married. Until the 1960s a Marriage Bar prevented women from working once married. [ Return to the article ]

24The term used to describe all manner of activities that the hen party engages in. [ Return to the article ]

25[EI 2012, 024] [ Return to the article ]

26Ibid. [ Return to the article ]

Works Cited

Abrahams, R.D. and R. Baumann. 1978. "Ranges of Festival Behavior." In Reversible World, edited by B. Babcock, 193-218. New York: Cornell University Press.

Abrams, L. and L. Fleming. 2010. "Everyday Life in the Scottish Home." In Everyday Life in Twentieth Century Scotland, edited by L. Abrams and C. G. Brown, 48-75. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Adam, H. and A. D. Galinsky. 2012. "Enclothed Cognition." Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 48: 918-925.

Adams, S. 2007. "Performing Dress and Adornment in Southeastern Nigeria." In Dress Sense: Emotional and Sensory Experiences of the Body and Clothe, edited by D.C. Johnson and H.B. Foster, 109-120. Oxford: Berg Publishers.

Allan, E. and M. Madden. 2008. Hazing in View: College Students at Risk: Initial Findings from the National Study of Student Hazing, March 11, 2008.

Åström, A. 1989. "Polterabend." Ethnologia Scandinavica 19: 83-106.

Barnard, M. 2001. Approaches to Understanding Visual Culture. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Beck, E. 1988. "Wedding Customs in the Paperwork Empire: Three Verbal Genres," Lore & Language 7: 43–60.

Bennett, M. 2004. Scottish Customs: From the Cradle to the Grave. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

Bronner, S. 2006. Crossing the Line: Violence, Play, and Drama in Naval Equator Traditions. Amsterdam: AUP.

———. 2012a. Campus Traditions: Folklore from the Old-time College to the Modern Mega-university. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

———. 2012b. Explaining Traditions: Folk Behavior in Modern Culture. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky.

Bryman, A. 2004. The Disneyization of Society. London: Sage Publications.

Burrows, R. and C. Marsh. 1992. "Consumption, Class and Contemporary Sociology." In Consumption and Class: Divisions and Change, edited by R. Burrows and C. Marsh, 1-14. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Charsley, S. R. 1991. Rites of Marrying: The Wedding Industry in Scotland. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Cheal, D. 1992. "Ritual: Communication in Action," Sociological Analysis, no. 53 (4): 363-374.

Cullum-Swan, B. and P. K. Manning. 1994. "What is a T-shirt. Codes, Chronotypes, and Everyday Objects." In The Socialness of Things: Essays on the Socio-semiotics of Objects, edited by S.H. Riggins, 415-435. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Driver, T.F. 1991. The Magic of Ritual: Our Need for Liberating Rites that Transform our Lives and our Communities. San Francisco: Harper.

Dyer, G. A. 1979. "Wedding Customs in the Office: A Note." Lore & Language, no. 3 (1) Part A: 73–4.

Eldridge, A. 2009. "Drunk, Fat and Vulgar: The Problem with Hen parties." In Feminism and the Body: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, edited by Catherine Kevin, 194-211. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Eldridge, A. and M. Roberts. 2008. "Bonding or Brawling." Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, no. 15 (3): 323–328.

Gregor, W. 1881. Notes on the Folk-lore of the North-east of Scotland. London: Folk-Lore Soc.

-----. 1874. An Echo of the Olden Time from the North of Scotland. Wakefield: E.P. Publishing.

Hayward, K. and D. Hobbs. 2007. "Beyond the Binge in 'Booze Britain': Market-led Liminalization and the Spectacle of Binge Drinking." British Journal of Sociology no. 58 (3): 437-456.

Hellspong, M. 1988. "Stag Parties and Hen Parties in Sweden." Ethnologia Scandinavica 18: 111-116.

Hobbs, D., S. Winlow, P. Hadfield, and S. Lister. 2005. "Violent Hypocrisy: Governance and the Night-time Economy," European Journal of Criminology no. 2 (2): 161–183.

Irvin, Benjamin H. 2003. "Tar, Feathers, and the Enemies of American Liberties, 1768-1776," The New England Quarterly no. 76 (2): 197-238.

Jackson, C. and P. Tinkler. 2007. "'Ladettes' and 'Modern Girls': 'Troublesome' Young Femininities." The Sociological Review no. 55 (2): 251-272.

King, M. 1993. "Marriage and Traditions in Fishing Communities." Review of Scottish Culture 8: 58-67.

Knuts, E. 2007. "Mock Brides, Hen Parties and Weddings Changes in Time and Space." In Masks and Mumming in the Nordic Area, edited by Terry Gunnell, 549-568. Uppsala: Kungl. Gustav Adolfs Akademien.

Leeds-Hurwitz, W. 2002. Wedding as Text: Communicating Cultural Identities through Ritual. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Levy, Barry. 2011. "Tar and Feathers," Journal of the Historical Society no. 11 (1): 85-110.

Livingstone, S. 1997. Scottish Customs. New York: Barnes & Noble Books.

Lynch, A., M. E. Radina, and M. C. Stalp. 2007. "Growing Old and Dressing (Dis)gracefully." In Dress Sense: Emotional and Sensory Experiences of the Body and Clothes, edited by D.C. Johnson and H.B. Foster, 144-155. Oxford: Berg Publishers.

McEntire, Nancy. 2007. "Blackening and Foot-washing: A Look at Scottish Wedding Pranks," in The Ritual Year 3, Proceedings of the Third International Conference of the SIEF Working Group on the Ritual Year, Straznice, Czech Republic, 2007.

McNeill, F. M., n.d. Hallowe"en: Its Origin, Rites and Ceremonies in the Scottish Tradition. Edinburgh: The Albyn Press.

Measham, F. and K. Brain. 2005. "Binge Drinking, British Alcohol Policy and the New Culture of Intoxification," Crime, Media, Culture 1: 262–83.

Monger, G .P. 1971. "A Note on Wedding Customs in Industry Today," Folklore no. 82 (4): 314-316.

———. G.P. 1975. "Further Notes on Wedding Customs in Industry," Folklore no. 86 (1): 50-61.

Montemurro, B. 2006. Something Old, Something Bold: Bridal Showers and Bachelorette Parties. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press.

Otnes, C. and E. Pleck. 2003. Cinderella Dreams: The Allure of the Lavish Wedding. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Pittaoulis, M. 2005. The Importance of Bachelor and Bachelorette Parties in Maintaining Friendship Bonds, Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association 2005.

Porter, J. 1999. "Aims, Theory, and Method in the Ethnology of Northern Scotland," Northern Scotland 18. Special Elphinstone Institute issue.

Roach-Higgins, M.E. and J. B. Eicher. 1992. "Dress and Identity." Clothing and Textiles Research Journal no. 10 (4): 1-8.

Santino, J. 1983. "Hallowe"en in America: Contemporary Customs and Performances." Western Folklore no. 42 (1): 1-20.

Schechner, R. 1993. The Future of Ritual: Writings on Culture and Performance. London ; New York: Routledge.

Shukla, P. 2005. "The Study of Dress and Adornment as Social Positioning." Material History Review 61: 4-16.

Skeggs, B. 2004. Class, Self, Culture. London: Routledge.

Slosar, J.R. 2009. The Culture of Excess: How America Lost its Self-control and how we Need to Redefine Success. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

Smith, V. 2007. Clean: A History of Personal Hygiene and Purity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Thompson, E.P. 1992. "Rough Music Reconsidered." Folklore no. 103 (1): 3-26.

Thurnell-Read, T. 2011. "Off the Leash and Out of Control: Masculinities and Embodiment in Eastern European Stag Tourism." Sociology no. 45 (6): 977-991.

———. 2012. "What Happens on Tour: The Premarital Stag Tour, Homosocial Bonding, and Male Friendship." Men and Masculinities no. 15 (3): 249-270.

Turner, V. 1969. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-structure. London: Routledge.

Tye, D. and A. M. POWERS. 1998. "Gender, Resistance and Play: Bachelorette Parties in Atlantic Canada." Women"s Studies International Forum no. 21(5): 551-561.

Urry, J. 2002. The Tourist Gaze. Second edn. London: Sage.

Van Gennep, A. 1960. The Rites of Passage. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Welters, J. 2007. "Sight, Sound, and Sentiment in Greek Village Dress." In Dress Sense: Emotional and Sensory Experiences of the Body and Clothes, edited by D.C. Johnson and H.B. Foster, 7-15. Oxford: Berg Publishers.

Williams, C.N. 1994. "The Bachelor's Transgression: Identity and Difference in the Bachelor Party." Journal of American Folklore 107: 106-120.

Winlow, S. and S. HALL. 2006. Violent Night: Urban Leisure and Contemporary Culture. Oxford: Berg.

Young, S. 2016a. "The Blackening," Heirskip, The Buchan Heritage Society

Young, S. 2016b. "Medieval Torture, or Just a Bit of Fun," Leopard, June 2016.