Cultural Analysis, Volume 7, 2008

Through the "Eye of the Skull": Memory and Tradition in a Travelling Landscape

Abstract: The vast oral culture of Scotland's Gypsy-Travellers was "discovered" by Hamish Henderson in the 1950s. Since that fieldwork period Traveller culture has undergone major social transformation. From an exoteric angle it is widely assumed that Scotland's "indigenous nomads" exist only in memory. Using the landscape of a traditional family camping ground to elucidate and revisit his culture, Scottish Traveller Stanley Robertson's "in-situ" knowledge suggests that, from within, memory is a vital force for the continuity and renewal of Traveller identity. My interviews with Stanley reveal parallels between memory, place-lore, cyclical journey and the progressive structure of learning. His beliefs suggest how, in interaction with oral traditions, memories function on many experiential levels to build creativity.

____________________

It has been a privilege to research the cultural traditions and creativity of the Scottish Travelling People,1 an indigenous and traditionally nomadic group credited with the guardianship of one of the richest oral cultures in Europe. (Neat 1996, vii) The pioneering collection work of Scottish folklorist Hamish Henderson in the early 1950s first brought the attention of non-Traveller society to the "magnificent folk riches" (Neat 1996, 66) preserved and nurtured within Traveller culture. Henderson was immediately captivated by the depth, longevity, dramatic sincerity and stylistic embellishment of the Traveller repertoire and his fieldwork yielded a quantity of ballads, songs and traditional stories which placed Travellers unmistakably at the forefront of traditional performance. Within Scottish society, Travellers gained a new venerated status as ubiquitous "tradition-bearers" (von Sydow 1948, 12-13) that remains uncontested today although the nomadic way of life that sustained this function is now believed to have virtually disappeared.

Hamish Henderson appeared to have stumbled upon Scotland's "most substantially ancient" culture, "lying totally unregarded and essentially unknown," (Neat 1996, 65-6) held together by blood ties, inheritable knowledge and ancestral memory. Looking earnestly for remnants of the past in his fieldwork he found them in vast quantities in the Travellers' age-old traditional repertoire, family structure, ancient clan names, and hereditary craftsmanship. In addition, Henderson's knowledge of Scottish history led him to view Travellers as an "underground clan system of their own," (Henderson 1981, 378) the tribal remnants of the Gaelic society broken by the destruction of the clan system following the Battle of Culloden in 1746. (Kenrick and Clark 1999, 6) Explaining to Henderson the difference between a Traveller and a singular migrant, one young Traveller told him, "that sort of lad just lives from day to day, but we live entirely in the past." (Henderson 1981, 377-78)

The Idealisation of the Past

These idealisations of the past now constitute problems of perspective and representation on a number of levels. An unintended consequence of this early collection period has been the development of a "devolutionary" (Oring 1975, 41) perspective through which "an intact culture is projected onto the past". (Okely 1983, 32) "Gleaned" and extensively collected in the 1950s (Nicolaisen 1995, 73), the creativity of Travellers apparently came to a standstill when the folklorists went home. Indexed, shelved and saved for posterity, the archives in the School of Scottish Studies are now where the interested minority can consult a recorded testimony of a now lost culture.2 This golden-age image conveys the impression that traveler culture in its present form has degenerated into the forgotten memories, faceless voices and culturally dislocated sounds of recorded reels on dusty shelves.

No longer visible by their distinct material culture—their wares and craftsmanship considered obsolete3 —the Travellers, it would seem, have disappeared completely replaced, if at all, by a "different" sort of Traveller. Contemporary media representations often accentuate this idea. Reports often distance settled Travellers from the their collective past while those Travellers, forced by the reality of closed camping grounds, to camp on increasingly marginalised and public spaces are branded "rogue" Travellers.4

Of course many Travellers have time honoured traditions and lead law abiding lives. But an increasing number are causing great distress to local communities by setting up illegal camps on green belt sites and building homes without the required permission. (Editorial, Scottish Daily Mail, March 22, 2005)

These recent comments are new expressions of an ongoing discourse in which Traveller identity is continually contested and misunderstood. As Betsy Whyte remembers from her 1930s childhood, "We Travelling people were judged without knowledge. Every crime, sin, foulness, acts of violence, cruelty, stupidity, and brutish behaviour under the sun was, to their [non-Travellers'] way of thinking, the heritage of all Travelling people". (Whyte 1990, 88) Even when expressed in nostalgic and cautiously positive terms such as "The Summer Walkers" (Neat 1996, vii) and "the mist people", (Whyte 1979, 24) these views reveal little more than the elusiveness of Travellers to settled society. In contrast to the distinct ethnic identity by which Travellers see themselves Traveller culture, since the time of its so-named "discovery," has been largely defined by a materially rustic form of nomadism, and regarded as a way of life already threatened with extinction. (Porter and Gower 1995, 3-5)

Memory as a Conduit for Knowledge, Continuity and Creativity

I would suggest that neither Traveller nor sedentary culture can be relegated to inactivity and that both have undergone similar processes of transformation. Older settled Travellers feel an understandable nostalgia for their lives "on the road", using words like "freedom", or phrases like "the old days", and "a trip down memory lane",5 to describe this sense of loss. The belief that their culture is dying out is common among the older generation who say "soon there will be no more Travellers".6 Others lament the loss of annual gatherings, such as berry picking, for their combined value as social, working and family occasions, and for the enculturation and practical responsibility they offered to younger family members.7

However, as Perthshire Traveller Fiona Townsley remarked, "Travellers have always adapted".8 In the absence of the real experiences once guaranteed by established cultural frameworks, Travellers have developed other routes to maintain the vitality of their culture and the strength of their social memory. In public and private performance—the key to real integration between people and lore—shared memories, retold with pride and experience, become energetic forces that revitalise the culture and strengthen family cohesion from within. (Bauman 1971, 33) The work of public representatives has sparked what some Travellers perceive as "a revival"9 through the sharing of songs, stories, and language, or in the teaching of crafts such as basket and flower making to Travelling children. By becoming authors, performers and educators, Travellers continue to revisit, verbalise and teach the importance of their traditional identity in self-created ways.10 Their work is an exemplary model for how memory and creativity combine to form the impetus that drives traditions forward. (Niles 1999, 15)

Relocating Memory in Place and Culture

From a distant angle, memory is a deceptively dormant force, disconnected save for bursts of nostalgia from the places and contexts of the present. Likewise, collections of memory, from recordings to heritage sites, can be deadened by imposed historicity and accompanied by perceptions of loss and social discontinuity. (Nora 1989, 19)

Zooming in on the experiential, a reversal of "the Gleaner's Vision", (Nicolaisen 1995, 71-76) Travellers seek to know the past as an access point which might inform the present.(Nicolaisen 2002, 9) One of many natural analogies for the past/memory which resonates within Traveller culture is that of "the carrying stream". (Macauly 2002) Memory is understood as a place in continual motion, a personal and collective archive of occasional11 knowledge which, like repertoire, is subject to periods of increased relevance, creativity or inactivity in contextual relationship to the life cycle. (Goldstein 1972, 82) Cultural continuity is ensured by strong, well-informed individuals who perpetuate traditions. (Niles 1999, 15) In Traveller culture the idea of memory as an ongoing stream of conscience makes the content of oral traditions contemporary, instructive and meaningful. Memories transmit not only texts but also a coherent learning processes, the worldviews that provide the foundations for confident creativity and individualism. When viewed as creativity, memory becomes an evolving store of knowledge, a source of informed "imitation" and individualistic originality. (Kristeller 1983, 110-1)

Looking in on Places of Knowledge

These core "academic"12 themes place narrative and symbolic representation within the didactic structure of Traveller culture. Moving beyond the linear into the idea of places as vessels or containers of tradition and symbols of memory (Ben-Amos 1999, 298), I will show that it is both the cultural structure of reciprocal and cyclical interaction between place and people (Robertson "Interaction between Man and Nature", 2002-2005), and the hostility commonly experienced when within sedentary culture that have given Traveller repertoires their breadth, creativity and resourceful quality. (Robertson "Poor Circumstances Rich Culture", 2002-2005)

Perhaps the most striking way in which Traveller traditions are used in Traveller contexts is for their implicit symbolic and metaphoric undercurrents. High importance is placed upon sensory experience, evaluation and effective communication. Their emphasis on the ability to understand and embody the characters, dramatic proportions and locations of traditional texts stresses the importance of an expansive understanding derived from use of all the senses.

North-East Scottish Traveller Stanley Robertson describes this intuitive methodology as "multi-dimensionality".13 Relating texts to places and places to people, in "being", "doing" and "relating" knowledge, Stanley illustrates how to "look in" and "draw out" vital information about the essence of his traditions. "Looking in"14 on settled society, the people "much maligned and persecuted for centuries" (Robertson 2001) have gained an extra edge of perceptiveness in often unpredictable surroundings. "Looking in" on the landscape is also a core aspect of how Travellers have constructed their traditional world and learned to "read" their environment.

Roads and the Lifecycle

This methodology finds illustration in the multiple narratives of Jack, the epic hero of Traveller tradition. On his quests Jack is reminded, "You are not without knowledge". (Robertson 1983, 18) He is aided by "ancestral wisdom, the power of nature and magic, and the realisation of his own potential", and ultimate success lies in his ability to apply the resources of his memory and keen wits. (Douglas 2007, 52) Using a geographic model to construct journeys as life paths these narratives conceptualize education as progressively attained knowledge.15 (Daniels and Nash 2004, 449) The commentary of Apache storyteller Dudley Patterson aligns well with the Traveller worldview built on "looking in" and "drawing out". Patterson ties these reciprocal themes together, ending with the resounding implication that the responsibility and impetus to remember lie with the individual.

How will you walk along this trail of wisdom? Well, you will go to many places. You must look at them closely. You must remember all of them. Your relatives will talk to you about them. You must remember everything they tell you. You must think about it, and keep on thinking about it, and keep on thinking about it. You must do this because no one can help you but yourself... Wisdom sits in places. It's like water… you also need to drink from places. You must remember everything about them. You must learn their names. You must remember what happened at them long ago. You must think about it and keep on thinking about it. And your mind will become smoother and smoother. (Basso 1996, 70)

Traveller tradition abounds with narratives that tie together geography and metaphor to recover ancestral memory. Founded upon the perpetuation of this memory, Traveller traditions caution that "only knowledge applied can become wisdom".16 Passed down in oral tradition, traditional texts contain "supra-narrative" associations, principles that enable their interpretation through multiple levels of perception. (McCarthy 1990, 11-12) Places "become" through memory, and memory teaches through place.

The Old Road of Lumphanan

The discussion that follows seeks to further unfold the triadic interaction between the Traveller themes of journey, memory and place. In the concealed Traveller topography of North-East Scotland, Aberdeen Traveller and internationally respected tradition-bearer Stanley Robertson has found an illustrative way to tell the story of his people's unique knowledge and cultural contribution. Key to his creative approach is the use and subsequent development of ancient teaching methods, which Stanley learned from his people on the road as a Travelling child. Speaking of his extended family, Stanley offers this tribute:

Never in ma life at any time, did I ever want to be anything else, than a Traveller. I just wanted to be amongst the people where I was born and loved…Nurtured and cocooned in love and happiness. And these people had a form of literacy that I never ever seen in the University. These folk could tell you the most wonderful things. They educated ye [you], and they took me on cultured excursions all ma life.17

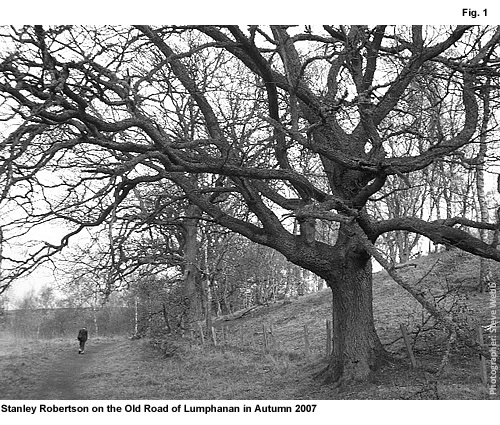

Stanley has clearly inherited this ability to educate through tradition. His "in-situ"18 narratives combine big ballads, songs and stories with family memories and place-lore,19 using the framework of journey to take the uninformed on "cultured excursions" into the social, material and elemental "rubric"20 of his culture. It is through his vision of a revered Aberdeenshire landscape, "the Old Road of Lumphanan," a traditional camping ground for many generations of his family, that I now attempt to describe his many-levelled journey into memory in its most vital, reverent and creative form.

A Landscape of Memory

Lumphanan lies twenty-four miles west of Aberdeen between the rivers Don and Dee in rural Aberdeenshire. In the summer months this village was on part of a network of cyclical journeys taken by Stanley's family as they followed seasonal work opportunities. Today deserted save for local walkers the Old Road of Lumphanan conceals a treasury of human engagement known only to the initiated eye. Retelling its past (as per Nicolaisen 1984, 271), Stanley recreates the road as it has always existed in his mind, as "a training ground." Stanley's vast repertoire comes of nights spent at the fireside hearing accomplished singers, storytellers, pipers and musicians. From instructing Stanley in the practical skills of building a camp, finding clean water, pearl fishing and hawking to imparting a detailed knowledge of the natural environment, its music and history, his family instilled in him a knowledge that always matched his stage of learning. However, the most striking aspect of his inheritance is his holistic view of the landscape. Stanley's expansive worldview encompasses the material, ancestral, ethereal and eternal as ever present resources. Lumphanan's spiritual geography is made manifest through his ability to interpret its natural "signs and portents" as he calls them, skilfully.21

"Through the Eye of the Skull"

It was in early childhood at Lumphanan that one of Stanley's key mentors, his Great Auntie Maggie Stewart, taught him how to access these expansive dimensions. After listening as he described to her a decayed animal skull lying by the side of the road, Maggie asked him what he could see from inside the skull. Stanley, then aged five or six, remembers:

I immediately wint inside the yak o the dead animal and I came to a place faur there were canyons, caverns, waterfalls mountains, animals o aa kinds and colours and smells, and the rick mi tick 22 o the inside unfolded tae me. And awa in the distance I heard the auld woman caa me tae come back tae me again. And I described tae her aa the things I experienced wi vivid colours and every sense inside honed up.23

Going "through the eye of the skull" denotes a methodology for the metaphysical relocation of self, one that uses a material access point to elicit a departure into "narrative time". (Nicolaisen 1991, 3) From this central point of vision anything may be intuitively understood by looking "through spiritual eyes".24 Gifted with the prophetic "mantle of the storyteller",25 Stanley has developed a transferable principle, "the spirit of discernment",26 which uses insight to teach tradition from all perceptible angles. Building upon his vivid memories and sense of loyalty to his ancestors today he has taken their creative potential further than any of his predecessors may have thought possible. Returning from this transformational experience, his Auntie Maggie reminded him:

Weel today I hae taught ye a valuable lesson and that is ye will find oot and discover mair frae gaun inside the rubric o the thing, than ye will by lookin' at a front dimension ... ye will learn mair in ten seconds inside a thing than ye wid looking and observing frae the outside.27

The Symbolic Landscape

On the Old Road where he first absorbed this principle Stanley urges visitors, often researchers or students of traditional song, to replicate this spirit of discernment and "cast off their mantles of academia"28 to gain an unclouded insight into Traveller traditions.

The gateway to the Old Road provides a similar point of transition. Passing this metaphoric boundary and "leaving the world of drudgery",29 Stanley remarks that we are now in a place of timelessness and ancestral connection. Emblematic of freedom and self-renewal the Old Road of Lumphanan never fails to offer new learning experiences and confirm his people's ability to create a rich culture in poor circumstances. (Robertson "Poor Circumstances Rich Culture", 2002-2005)

Though camping has not been permitted here since the mid-1950s, this three-mile stretch of woodland track remains a focal point for his family tradition, which fuses natural landmarks with history, such as the murder of Macbeth, inherited knowledge and memories of ancestors.30 (McCombie 1845, 1083) However, the core narratives that bring the Old Road's meaning to life are experiential memorates and traditional repertoire passed down through family. The Old Road of Lumphanan was once part of the ancient network of droving roads that formed a central crossing point for cattlemen between highland and lowland Scotland. While this aspect of the road reaffirms Stanley's sense of belonging there, tradition tells him "this road has known Travellers since time immemorial".31

Leaving the gate behind, Stanley treats the landscape as an evolving record of the past, one that unfolds in his step-by-step building of a walking material and symbolic alignment, a sensibility reflected in his knowledge of the road's rich narratives. In contrast to the "official" map, Stanley's family describe the rivers Dee and the Don as supernatural beings (Robertson 1988, 128-29):

Ma mither used to say that this particular land [here] between the river Dee and the river Don - and they used to say lang ago that the Don wis the warlock and the river Dee wis the witch. And this land between it wis for her bairns. This land wis oors aa richt because there's only twa hooses. But this road has been known for many, many supernatural happenings ... there's a lot o happiness on this auld road. And every time I ging up it I could aye sort o feel the spirits o the past …32

These inside representations of the landscape imply a worldview of reciprocal nurture and give an impression of the stewardship, idealism and symmetry that is part of the road's muse. Landmarks become "actualisations of the knowledge that informs them" (Basso 1996, 57), reflecting the security offered to the community by the land. (Robertson 2005) Symbolising black and white magic in balance, the spring well which marks the life-giving, social "heart's blood of the road" (Stanley often uses ballad commonplaces in his everyday speech. See this also in Buchan 1997, 145) is similarly protected, purified by the presence of a rowan and oak tree on either side.33 As these themes unfold, Stanley's narratives bring a growing realisation of why, in much simplified outsider terms, the Traveller way of life has been associated with an imagined "closeness to nature". (Nord 2006, 46)

The traditional camping grounds of Scottish Travellers have formed private community spaces where their skills, values, and rich culture could flourish. Journey, which for many settled Travellers is today more an ideal than a reality, still signifies a release from cruel treatment and the social constraints of settlement or enforced schooling. Journeys to the Old Road, which Stanley and his relatives have described as their "spiritual home", continue to renew feelings of purpose and vitality that are echoed in many Traveller narratives. In sharp contrast to city life Stanley remembers Lumphanan as a place of plenitude and visual splendour:

Because this wis the place where ye enjoyed the best pairt o yer life! Ye used tae wait until ye could feel the first smell of broom on the air. And how happy ye wid be fin ma father wid get his horse and his cairt, and we'd tak aa the things that ye needed, and just left the hoose in Aiberdeen, and ye wid come oot intae the Old Road o Lumphanan. As I come up this hill, I was so happy. And I lookit round this beautiful, glorious clear sky in a summer afternoon. And in ma vista before me, I could see the Mither Tap o Bennachie. I could see Benahighlie with its very distinct little cairn. I could look over by Tarland and see Morven. I could look further round I could see Lochnagar. And then I could see the distinct shape o Clachnaben - which looks like a lady lying down. And ye know ma spirits were very, very elevated … But I remember coming down to ma folk. What a welcome there was. And on the edge of the glimmer, the fire, there was a big biling kettle always filled tae the gunnel. And this woman gave us tea and 'duke sharras' this is ducks eggs. And ye ken this, I just thought to maself … The Kingdom of Heaven couldna be any better than what this was.34

Though the landmarks of the Old Road are the natural vernacular features of the Scottish landscape, the traditionalisation of this space is built on analogies. In its inner enclosure and outward expansiveness Lumphanan conveys a sense of natural safety and orientation, with curiosity for what lies beyond. Stories depict the Old Road with its surrounding hills as a "land betwixt and between",35 a liminal space where, it is implied, a person's greatest potential can be realised. (this is Stanley's description though it matches many conclusions drawn by folklorists. See Abrahams 2003, 213).

Place as Memory and Memory in Place

The principle of "going through the eye of the skull" is an endorsement of individual experience and exploration. Stanley, who has since invented a multitude of similarly-illustrative techniques, teaches visitors how to access and experience this "place" within themselves. Now, as an adult and exceptional storyteller, these abilities have become finely tuned. He remembers:

Ye had a whole world at your command and that's where pure creativity is. And that's where real story telling and writing and aa these things come from…it's looking wi yer spiritual eyes…ye've got this inner eye…And when that eye opens…Nothing's a barrier to you. You can go to any place…36

This exploratory approach creates his experience-centred dialogue with the Old Road. Held within its geography, transient like the passage of time and season until narrated into story-time, Stanley's ability to bring out stories in this way often has the effect of connecting others to the place of their own muse or source of confidence.37 One visitor, now a storyteller, related how Stanley's tale of "Tammy Toddle"38 caused her to revisit her father's stories. She returned from this metaphysical journey with a renewed faith in continuing with her inheritance.

| Tammy Toddle (excerpt) | |

| Tammy Toddle he's a canty chiel | good humoured, person | Sae cousie and sae canty | kindly | And the fairies liked him unca weel | very, well | And they built him a wee hoosie | a little house |

| (Higgins 2006, CD 1, Track 6) | |

In Stanley's narratives the supernatural world is separated only by thin veils. His story of Jinty, who lives in the fairy kingdom under the Old Road and is able to come to the surface to play with a Traveller child because she believes reiterates an appeal to the importance of memory (Robertson 2002-2005):

Whin fairies are nae remembered by folks then they jist vanish intae oblivion. Fit this really means is that they gang intae hiding and winnae come oot for hunners o years. Sometimes the conditions between men and fairies become strained and the fairies jist close themsels hinnie awa frae mankind.39

Underlying this tale is a reiteration of the importance that remembering has to the continuity of traditional knowledge.

The "rick mi tick"40 of Lumphanan unfolds, paradoxically, through a form of forgetting. Using the framework of progressive journey Stanley's narratives lull visitors and audiences into "the land where stories grow"41 through the distracting activities of walking and listening. Stories invoke the footsteps and voices of ancestors, the sounds of ancient music carried by the wind or supernatural visions of ghostly beings and otherworldly tribes. Stanley's beliefs add a conditional element to such deeply-informed experiences: the necessity of attentiveness, "through a vigorous conflation of attentive subject and geographical object, places come to generate their own fields of meaning…Animated by the thoughts and feelings of the persons that attend to them, places…yield to consciousness only what consciousness has given them to absorb". (Basso 1996, 56) With "every sense inside honed up", "the world itself begins to breath", (Ingold 1993, 16) as though the road itself is memory, and nature a co-existent actor that can impose the past upon the here and now.

The Summer Seat

One story that illustrates these themes is "The Summer Seat", which describes a place tinged with the tragic memory of a Traveller woman named MacPhee found murdered there shortly after the First World War. Although she was denied the justice and concern usually given to any member of the settled population,42 Stanley always stops here, singing a song in her memory. A non-Traveller visitor, poet and psychic medium, Steven Webb,43 was asked to "tune in" to this event. He recounts what followed, "What I was guided by spirit to do…was to actually taste, to lick a bit o the bench [laughs]…To get a taste of the metal, you see? Where the paint had rusted away a bit. And then…the next thing, it was very strange, was to kiss the stone wall, a wee bit of mossy stone wall".44 Webb explains the logic behind these actions: "[I had] to ask the stones and the bench and the trees to tell me the story that they witnessed. Because the stone saw it…the bench saw it…I mean…it's a bit like they were there"!45

This experience aligns well with the ideal of the road as a representation of the all-seeing, restorative power of nature. A poem connected with place unfolded as the spirits of Traveller witnesses recounted the event, "I was feelin aa the emotions coming through me".46 In addition to exposing the acts of local deception surrounding Lilian MacPhee's death the poem, which gives voice to the thoughts of Lilian MacPhee, poignantly acknowledges her sadness that her life is remembered today only because it was so violently cut short. Her story provides a striking example of memory materially self-represented in the landscape.

Poem For Lilian MacPhee (excerpt)47

You could look to find the guilty

A cold case for yer fame

Or ye could get to know me

Who I am behind my name

I went straight to Christ wi the angels

I've always rested in peace

It's only ever the guilty

Who hide from love's release

It's only he who sits here

On the Simmer Seat wi me Summer

And only he who cowers in the pit

Below yer feet ye see…

Marking the spot where the murder happened almost one hundred years ago lies her "body," a fallen tree, while her earthbound, nameless killer is locked forever in the remains of an adjacent dead tree stump. Within this event is a "story of love and faith",48 a reassurance that a higher balancing force is in operation and that the unalterable past may be transformed and resolved through commemoration.

The story that gives material form to this memory suggests the depth of human entrainment and elemental agency invested in this landscape. (Clayton 2001) In the narrative creation of the past how the "keepers of these landscapes, tell stories that explain [their] existence", is an implication that all levels of the material and unseen are in continual reciprocity. (Glassie 1994, 962) Stanley's son, Anthony, understands these different levels as "frequencies".49 "It's like having antenna, if you can't tune into the frequency then you won't know it's there".50

Memory, therefore, is both the key and strongest safeguard to the esoteric type of knowledge held within Traveller tradition. As Donald Braid points out the degree to which the "journey of following" narrated events is incorporated as a personal resource depends upon the listeners' particular experiential contexts. (Braid 1996, 9, 16, 26) The case discussed requires a "suspension of disbelief" that many sceptics could only make whilst conceiving of themselves as being in a narrative space.51 (Edwards 2001, 82; Hufford 1995, 22) On returning they will leave the Old Road behind, safe in the world of "make believe".

Stepping Stones to Knowledge

On another level, the road is celebrated for its ability to elucidate the progress of human life through activity and journey. Like the verbal emphasis of the Cant language,52 the interface of the road teaches through response—by walking, listening, making, doing and discerning. Its metaphoric representations are designed "to make the mind move,"53 an allegory for the therapeutic value of a new way of seeing, or as an opportunity, as Stanley puts it, to "rest and be thankful"54 on the "stepping stones"55 of life's path.

As a child Stanley remembers passing milestones on the road. At these places his father would review a learning principle, asking questions to make sure that he had been understood. Stanley's approach to teaching, writing and performance is structured in much the same way. When singing a ballad for illustration he often stops between verses to elucidate symbolic, archaic language, historic connections, or events in the plot. Stanley's new vision of the Old Road recreates the cyclical structure of Traveller life, a journey of challenge and learning broken up by refreshing stops where one re-gathers personal energies or allows time for self analysis before moving on. Knowledge is accumulated in rhythmic progressions between journey and rest, learning and contemplation. Stanley explains that:

'At each stepping steen they wid sing ye a song, play ye a tune, instruct ye. So you could sit doon, ye could look behind, at faur ye come fae. Ye could see maybe the auld Mill o Aiberdeen. And then, at the next stepping stone, ye could sit doon, analyse yerself and see how far ye've come, and how far ye're gaun. So yer stepping steenies was the sort o resting places whaur you were taught something. And it represents the progress of the Travelling people'.56

An "Elemental" People57

Explaining the capacity of his people to stop, listen and learn from their environmental resources, Stanley emphasises that to "catch the vision"58 of this road involves receptiveness to its subtle frequencies. The vital spark of his stories, songs, and, later, his books, have been fed and inspired by a detailed awareness of the elements:

when ye went tae yer bed at night, aifter ye heard their music and the songs and the stories, just being amongst them. And ye lay in yer bed at night, ye could listen tae the rain. Fin ye hear the rain faa'in on the camp, this precipitates doon these torrential notes…And ye could hear aa these bonnie wee pipe tunes getting played by nature. And ye listen! And ye got all yer timings of yer tunes off o just listening to nature. And ye could look at the rain makin these beautiful intricate patterns upon the canvas. And ye got telt stories by an unseen voice, and yet these stories were all in the pattern. Ma Mither used to say,

'If ye listen to mither nature, she's a living being. What does she say to ye? What does she tell ye?'

The Travelling folk were very elemental…very much in tune with the elements [and] what was gan on. And that's where we learnt wir songs, stories, music…59

The sound of Traveller singers can have a dramatically expressive and emotionally raw edge, whilst timings within single phrases can vary greatly. Individuality is a source of family pride and, as in the case of traversing the Old Road, a greater emphasis is placed upon evaluation, understanding and an internalisation of symbolic structures and imagery than upon stylistic uniformity. Stanley equates this distinct style with the absorption of "elemental" timings. Traveller tradition has chosen to perpetuate many natural ballads of poetic and descriptive beauty,60 including those containing the common theme of seasonal movement. Stanley relates the following family song to another landmark, "The Tree of Life", symbolic of socialisation and growth, 61 which metaphorically references the transition between childhood and maturity.

The Seasons (excerpt)

The hills are clad in purple

The autumn winds they are sighing

For a beauty growing old

The grey grouse and the heather

And the evenings where we played

I'm thinking of my childhood

In a very special way.62

Auld Lumphanan's Fame63

The ultimate cohesiveness that continues to bind Traveller culture is kinship and through memories of extended relatives the Old Road becomes a "hall of fame". Nowhere does Stanley feel closer to his "folk" than at Lumphanan, an affinity kindled from memories of times spent among a remarkable line of family singers, musicians and storytellers going back many generations. Though perhaps the most well-known relative was his aunt, Jeannie Robertson, he also credits his mother Elizabeth MacDonald, his father William Stewart, his Uncle Albert Stewart, his great grandfather Bill Macgregor, and Maggie Stewart for their wealth of folklore.

At the heart of the road is the social environment of the camping place where his family camped, cooked their habben [food in North-East Traveller Cant] over fires made with broom, exchanged experiences, and celebrated their community with songs, tunes and tales late into the night. Encompassing everything from country hits or children's songs to big ballads and tales, Stanley's formidable memory has grown from a lively atmosphere of listening and family participation from his earliest years.

For Traveller children the Old Road became the focal point of their education. Though continually bullied and sent to the lowest class at school Stanley recalls how the strength of his family tradition "made you feel so very special"64 and counterbalanced the social isolation he experienced there. The mechanisms of traditional education created unshakeable bonds between family members that have almost no parallel within the school system. Stanley told me, "It wis a complete learning centre better than ony school or college I ever went to". (Robertson, in press)

Stories could be repeated, stretched over several nights or, by association and competitive spirit, lead to more embellished, larger-than-life versions. Stanley's favourites were the supernatural stories that "wid terrify ye to death",65 or the Jack tales, several of which are geographically localised on the Old Road. Stanley explains their function:

The Jack Tales are tales of encouragement: These are tales to lift all the Travelling folk, (most especially the children) from the despair that is felt within the city and the prejudices of many of its people. For Jack is a marvellous and exemplary character—who always manages to get over all the evils of life, by finding worth within himself, and from this gaining faith with his fellow being—because Jack is not alone along the paths of truth—he is guided and assisted by helpers, who are very important to him. (Robertson 1988, 119)

Jack on the Old Road

The "King of the Road" is Auld Cruvie,66 the ancient "all-seeing" oak tree. Respected for his age and stature (it is regarded as gendered), "Cruvie" is the focal point of one of Stanley's key "Jack" narratives. Every fifty years, during the solstice, all the trees of the road come out to dance, revealing long-hidden jewels. Jack is successful because he has the wisdom not to take more than he needs, whereas the greedy Laird of the Black Airt is still filling his pockets with treasure when the roots of the returning tree crush him. Stanley uses this tale today to illustrate the topical environmental message that overpowering greed and disrespect for nature will result in humanity's ultimate demise. He believes this story has been reactivated in tradition because the world needs a reminder of the eternal bond between humans and nature.

Memory, Performance, and the Senses

In the "intensely human habitat" of narratives in place Traveller culture has no shortage of mnemonic devices. (Nicolaisen 2002, 9) The sound and vocabulary of Traveller traditions in performance relates to a "folk-cultural register", in which continual exposure to the commonplace phrases of traditional ballads and stories has added adeptness for extended descriptive embellishment to the individualised nuances of everyday speech. (Nicolaisen 1990, 44) Stanley says proudly, "Travellers were masters of hyperbolae"!67 In the use of sound, imagery, alliteration and metaphor to convey emotional and situational content, he remembers how "everything was magnified"68 to communicate full dramatic effect.

Stanley's supply of descriptive phrases, comparative devices and capacity for immediate retort, such as, "Fake avree frae me ye auld cravat cos I widna gee ye as much as a lick o mi beard", finds the humour and visual impact in every situation. Expressions like "drooshie and dry" to describe thirst and "blue sparks and fiery ends" to describe anger are just two examples of how he has fused his character to this inventive vocabulary with the goal of adding an extra descriptive edge to his speech and performances. (Robertson, in press)

Barbara McDermitt has noted how Stanley learned and remembered stories, sometimes after long periods of inactivity, by incorporating a spectrum of senses, by repetition, through use of numbers and symbols, or by drawing out the memory through progressive revisualisations of place:

First of all I try to remember the actual place where I heard the story, maybe Lumphanan or someplace camping. I try to remember the setting, everything, even the smells, everything to do with the senses. I try to picture the storyteller, the voice, gestures, maybe rhymes or riddles. As I picture the actual event the missing parts of the story come back to me. It's a fusion of fragments…Once I hear a story, it's never really lost. (McDermitt 1986, 361-62)

Above Stanley describes a methodology similar to "going through the eye of the skull", using a three-way ritualised process of relocation, from the revisiting of the situational core to a rebuilding and articulation of its content. The journey from memory to renewal represents the creation of an individualised, experientially-grounded and timeless performance space.

As Maggie Stewart later emphasised, "You hae [have] understood that there are two times on this earth, the here and now, and story-time".69 Like breathing in and out memory becomes a referential blueprint, the rubric of a text in progress. Using the material and traditional as points of departure the land where stories grow creates a new "place" in narrative time, a coexistence world where knowledge, creativity and "occasionality" meet ancestral memory and the wisdom of the eternal.

Through the use of visual aids to recreate memorial places in the mind ballads, songs and stories designed to "mak a lang road short"70 also became the "instruments of oral knowledge". (Robertson, "The Old Road," 2002-2005) Stanley remembers, "It was lovely to be at Drum, and then hear the ballad 'The Lady o Drum' or to be at Udny and hear 'Bonnie Udny' or Fyvie and hear 'Tifty's Annie', at Tarland and hear 'Corachree' or Monymusk and hear 'Johnnie o the Brine'. As a child I thought that everybody knew these songs and I did not realise until a later age just how precious these gems were". (McDermitt 1986, 9) His brief summary of nearby song locations conveys a fleeting sense of the wider orientation points of the Traveller landscape of Scotland. Beside the glimmer [fire] at Lumphanan Stanley remembers ballads were delivered with deliberation and immediacy "as though they happened yesterday",71 their texts, plots and circumstances becoming regular subjects of discussion and social debate. Whether visiting historic ballad locations or teaching in a classroom Stanley draws listeners through a connection with ancient places towards a confident and well-rounded understanding of the human situation within the ballad.

Local ballad "Busk Busk Bonnie Lassie" is associated with the spectacular mountain pass of Glenshee in Highland Perthshire. (Robertson 1984, Track 3) Known in Traveller tradition as an ancient "bridal path", 72 the soldier's invitation to his sweetheart to walk with him over Glenshee becomes a proposal for marriage. The soldier's potentially fateful departure implicit in the language reveals the song's "anti war sentiments"73 Visiting this location, Stanley reminded me, "Now, when you sing this song you hae a vision o this place in your mind and you can bring it into the song".74

| Busk Busk Bonnie Lassie (excerpt) | |

| Fain I wid gang wi ye | willingly, would, go with you | For yer aye on my mind | always | It was never my intention | For to leave ye behind | you | Busk, busk bonnie lassie | Aye, and come awa wi me | away | And I'll tak ye tae Glen Isla | take | Near Bonnie Glenshee | Fain I wid gang wi ye | But wi ye I daurna go | dare not | Fain I wid gang wi ye | For I love ye so | Busk busk … | An dae ye see yon high hills | do | Aa covered wi snaw | all; snow | They hae pairted mony's a true love | parted many a | An they'll surely pairt us twa | two | Busk, busk … | An dae ye see yon shepherds | do | As they mairch alang | march, along | Wi their plaidies pu'd aboot them | pulled, about | And their sheep follae on | follow | Busk, busk … |

The many local variants of this song suggest a cultural mapping of memory similar to that discussed by Judith Okely. In Traveller tradition visual and spatial associations with the text are richly developed and, whilst founded by default upon a sense of the past, informed by "orally transmitted traditions passed down through families and communities" (Davies 2007, 41), this co-exists with literary or contemporary knowledge, personal experience, and an awareness of how other groups have interpreted the songs. The experiential amounts to a knowledge base of all that is remembered (Nora 1989, 13) and, beyond socio-cultural boundaries, the universally applicable content of ballads can evoke infinite collective contexts for memory, strengthening their potential to teach. The Travelling way of life has made this reverent approach to traditions in performance a cultural strategy.

The Multidimensional Ballad

The idea of "fusion" appears well-suited to these multiple layers of engagement. To the performance of ballads through place Traveller tradition adds an ethereal element that moves beyond their histories, encoded texts or creation in sensory dimensions. Songs entwined with the memories of much-loved relatives (Williamson 1985, 4) become relived genealogies inhabited by ancestral voices, and Stanley brings the memory and presence of many people to the stage. Performing with sincerity, respect and involvement Stanley teaches that "when you sing a tribe comes with you".75 At times Stanley is moved to tears by the ballads he calls "his dearest friends".76 Their emotional content is magnified as much by the timeless bonds they create with closely-felt family, as by his interaction with their events. When performing family songs their presence, participation, and direction are often sensed strongly.

His Auntie Jeannie, in particular, is an ever-present mentor, "And the tears just used to stream doon ma eyes, just powerful, and she still dis it yet, she's been dead for aa these years and she still comes through me. It's really frightening. But I ken she's teaching me…She wants me to get all her phraseology".77 Stanley says, "A real balladeer fuses wi his ballad and the whole spirit o the ballad is there. Yer there in spirit and ye're there in body".78 Using the same principle of internalisation and externalisation, drawing in the ballad, and relocating himself to the heart of the song, Stanley's intention is to become a "multi-dimensional singer",79 a channel through which the song is able to come forward. Like a suspension of self,80 each performance becomes a reverent renewal of an unbroken living link between singer and song.

Stanley's ballads are intensely visual, "lived in", and emotionally delivered commentaries:

I see them like films or plays in front o me. Yer the producer, the director, the actors, the narrator…You're every character in it. And you see it. And you've got to convey it! I see it like a big screen. I see it in a cinemascope Hollywood production. Every colour's there, and everything's there. And I want folk … to see this vision.81

Stanley has been much influenced by his Auntie Jeannie who explained to him as a child that, "ballads live in the air all around you. Breath them in, let them fill aa your senses, and then, tak them oot bonnie".82 According to Stanley, the full implications of her words have been greatly misinterpreted by scholars. Stanley says, "Jeannie meant, 'just sing it as best as you can'";83 His emphasis upon connecting with ballad location and content reflects his sense that a heartfelt performance is preferable to a "beautiful voice"84

High up in the air ye'll get the words o the ballad and down below further ye'll get the melody. But in between that space between the melody and the actual ballad itself, the words, lies all the magic of the ballad. And that's far The Mysie is. And it's once yer able to go in and take that out and discover it…And then that's the thing that gees ye the shivers doon yer spine. And that's fin ye get emotionally involved in the ballad.85

Catching The Mysie

Like Jeannie's, Stanley's mentoring has had a transformational effect. Sam Lee, a traditional singer much influenced by Stanley, describes this "inside" approach, "I felt as though I was standing aside looking at myself performing. I was outside myself…just overawed by this power. Somebody else seemed to be singing through me. Then I realised, that was the brilliance of the ballad".86 Reaching this tuned-in "place" Stanley's philosophy begins to make integral sense. To be a good storyteller, he says, "you must be willing to give up something of yourself", 87 an approach described by a local storyteller as being open to the "childlike innocence"88 that is part of even the most disturbing stories.

Stanley's ultimate performance goal is The Mysie,89 a term he uses to describe music's moving, transforming effect when sourced in visual connection, attentiveness to language, imagery and event, and emotional involvement. Felt as commonly by listeners as singers themselves, in Stanley's mind The Mysie, which can "mak yer hair stand on end", 90 is a tangible force, a gift, rather like the mantle of the storyteller, which bestows itself upon the sincere performer, at times adopting the human and elemental qualities of a deity-like being. An experience of The Mysie spells a heightening of individual and collective thought, in performance, the creation of a conjoining "atmosphere". Stanley describes this as "feeling shivers down your spine", 91 and, reflecting his own deep religious faith, as an appearance that signifies the presence of God. Its ancient power is such that Stanley says, "When ye've got that nobody can take it away frae ye",92 and through transferable techniques like "the eye of the skull", a tradition bearer becomes part of a dialogue with eternity.

The Land where Stories Grow

Stanley's commentary on The Mysie sums up what is perhaps the most compelling aspect of memory to Traveller tradition—its role as a human treasury of immeasurable wealth. Describing his inheritance as a silver chalice to be nurtured and passed on (Robertson, 2005), Stanley attempts to share his culture in the face of change, an act that embodies the belief that nothing is gone unless it is forgotten. By choosing to remember Travellers, so often outwardly disenfranchised, have prioritised the "communal bonds" (Yoors 2004, 7) of family ties and human exchange in order to celebrate their heritage as a source of pride, ownership and creativity.

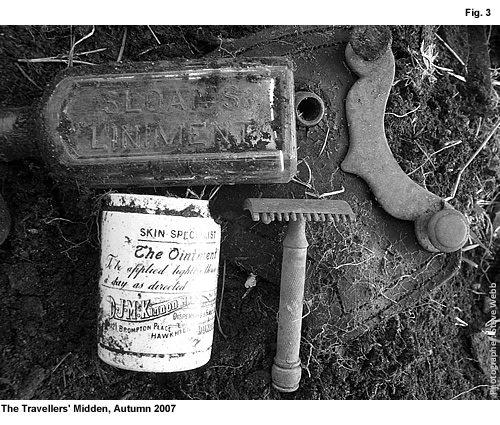

Without Stanley's active belief in its continuing vitality, the Old Road of Lumphanan would be nothing more than a dirt track. Combining memory, tradition, and creativity, he has recreated its understated landscape as a living and monumental archive of Traveller life. Today the only physical trace of the road's alternative history is carefully buried in the Travellers' midden, 93 the place where Stanley says they disposed of rubbish or buried things for posterity.94 Concealed in layers, the midden divulges artefacts which relay a history of human dwelling. From the fragmented and unknown to the objects of living memory, the pieces of broken china, horse brasses and tackle, or cracked pots, cups and basins confirm the ancestral and emanate belonging. Nearer the surface objects become more complete in their direct relationship to remembered people. Stanley's discovery of his father's old-fashioned brass razor led him to recount tales, songs and anecdotes of his memory.

Such material becomes a conduit for new narratives that use a sense of the past to objectify the present. Within Traveller culture, the pervasive themes of cyclical renewal or life as a journey reflect a worldview instilled by the practical, descriptive, and symbolic richness of Traveller education in which the guidance of family, tradition and nature is always accessible when sought.

From the childhood game of making Brackos, Stanley learned to construct pictures and tell stories from gathered natural objects. Not only do these unfolding narratives hone descriptive abilities, they also provide methods for reflecting on life and for self-analysis. Today this skill allows him to perceive and arrange constellations of symbols, to create stories of expansive and enlightening narrative meaning from apparently unremarkable objects.95

Stanley's life as a Traveller and his family memories of the Old Road have taught him to cultivate the spirit of discernment and the ability to read his environment from the inside. Tradition manifests itself in the connections of knowledge drawn between the visible and the unseen and, in Traveller belief, material objects and oral traditions alike carry energetic properties, tangible shadows of the lives and experiences they connote. Handed down in his family is a belief that "the eyes are the mirror of the soul". "Looking in" on the landscape, Stanley's environment has become a teacher, and a reflection of all human situations.

Stanley's work today honours the memory of his ancestors and carries their knowledge forward in a unique and individual way. By passing on the mantle of tradition with an informed knowledge of its symbolic importance and an awareness of his sources, he, in turn, becomes a teacher and ensures its continuity. Memory, experienced through tradition, provides an ancestrally sanctioned route for the development of solutions to current challenges. Catching a glimpse of the Old Road, visitors return through the eye of the skull richer in knowledge and transformed by the experience of a world perceived anew.

In the dedicated work of sharing the experiential within their culture, Traveller performers such as Stanley communicate a worldview that can cross the boundaries of outside memory, using tradition as a force to instigate positive changes in popular belief. Moving past the "tip of the iceberg", between folklore study and the experiential language of tradition, terms such as "multi-dimensionality" can suggest ways of looking anew at the complicated dynamics of memory in traditional contexts. "Looking in" on the sensory dimensions of the experience of tradition elucidates how places exist in memory. It suggests that these places of memory serve as a motivational and creative force in tradition because of their human connections.

To sum up, the Old Road of Lumphanan is a landscape humanised by tradition. Its land is rich with the ancestral memory of learned knowledge and narrated in the distilled essence of experiences represented by archetypal figures like Jack. Just below the surface, from the stories and songs told of people that lived once or never, to the intensely individualised associations of living memory, the vertical meets the horizontal, the continual and immediate. Going through the eye of the skull creates a place, "the land where stories grow", where these levels of knowledge and immediacy converge, resulting in moments of epiphany or timelessness, the Mysie, in the realm of experience. Journeying through traditionalisation in the landscape, the evolving present meets with the vertical strata of commonly held, cross-generational truths, converging with layers of sensory experience in the here and now. In its spirit of renewal, "Auld Lumphanan's fame" exists because each feature of its landscape contains multiple layers of association, the many levels of experience between the exoteric and esoteric which inhabit the memories of every human being.

To storytellers Auld Cruvie exists as a symbol of environmental truths. To those who have never "met" Cruvie, it is an image of their own association and, to visitors, a reminder of nature's balance, or a place of luck and light-hearted ritual. To Stanley's family Auld Cruvie on the Old Road of Lumphanan is a place of many deep and personally associated memories, an icon of their history and belonging and, ultimately, a representation of life, longevity, hope and faith. In an archetypal sense, Auld Cruvie emblemises the growth and rejuvenation of the treasures of the earth, an ancient knowledge of great worth and substance, sourced from the deep well of tradition. The Old Road of Lumphanan viewed through the eye of the skull is the sum total of all these parts: memory, tradition and creativity in a continual state of interaction.

The transition from the material to the experiential is made possible by journeys of the mind "through the eye of the skull". Travelling through the eye of the skull, or breathing in his chosen surroundings, Stanley understands that people and places are an ever-present part of the self and may be revisited by the mind and through the intensity of memory from any physical location. Memory fuelled by tradition is a place in the mind; it comes from the past yet lives in the moment of recollection. Everyone continually relives and recreates from their past, but it is the attentiveness of the going within that brings the creative spark of The Mysie to the moment and ensures the vitality of tradition. To look at memory as a multi-layered process of tradition, dwelling and humanisation is ultimately to ask "Where does memory live?" In Traveller tradition this is not "entirely in the past", but in the consciousness of its eternal presence.

1Scottish Travellers are also referred to in public and legal contexts as "Gypsy/Travellers". [ Return to the article ]

2Fearing the prejudice of the settled population, some Travellers choose to conceal their identity to the extent that they will not associate themselves with their past even in family situations. [ Return to the article ]

3Traveller objects of memory in a settled world have become increasingly important. Photographs are increasingly treasured and become proudly displayed visual props to a substantial genealogical knowledge. When I visited Fife Traveller Duncan Williamson he lived in one room of his welcoming home, and was surrounded by brass; harnesses, horseshoes and beautifully polished objects associated with his life and accumulated skill as a horseman and trader. The same show of garish pride is apparent at gatherings of Traveller culture such as Appleby Fair in which displays of skilled horsemanship (often from very young children), competitiveness and exchange compliment an increasing stock of memorabilia in the form of CD's, books and DVD's. [ Return to the article ]

4Many Scottish newspapers describe Travellers this way. See for example 'Anger as council offers £25,000 salary for gipsy co-ordinator' Scottish Daily Mail, June 14, 2006 or 'Rogue Camp almost caused multi-million pound pull-out' Evening Express, July 12, 2006. [ Return to the article ]

5EI 2008.098 [ Return to the article ]

6Conversation with Fiona Townsley, Perth, 16.8.08. [ Return to the article ]

7Conversation with Traveller resident at Doubledykes Site, Perthshire, 15.8.08. [ Return to the article ]

8Conversation with Fiona Townsley, Perth, 16.8.08. [ Return to the article ]

9Conversation with Fiona Townsley, Perth, 16.8.08. [ Return to the article ]

10Some examples of Traveller publications include:

Stanley Robertson. Exodus to Alford. Nairn: Balnain Books, 1988.

Stanley Robertson. Nyakum's Windows. Nairn: Balnain Books, 1989.

Jess Smith. Jessie's Journey: Autobiography of a Traveller Girl. Edinburgh: Mercat, 2002.

Jess Smith. Tales from the Tent: Jessie's Journey Continues. Edinburgh: Mercat, 2003.

Jess Smith. Tears for a Tinker. Edinburgh: Mercat, 2005.

Sheila Stewart. Queen Amang the Heather: The Life of Belle Stewart. Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2006.

Duncan Williamson. The Horsieman: Memories of a Traveller 1928-58. Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2002. [ Return to the article ]

11I have taken this thematic idea from recurring literary descriptions of Travellers and Gypsies as the ever-resourceful providers of "occasional labour". This idea seems to resonate well with how traditional lore functions within Traveller culture as a store of skills and knowledge to be recalled and applied to life contexts as and when required. [ Return to the article ]

12Now often sought as a tutor or lecturer in academic contexts, Stanley Robertson often pits the strength, reliability and detail of his "natural" knowledge against the oft-times sterile and misinformed approach of scholars. [ Return to the article ]

13Stanley Robertson's performing and teaching methods focus heavily upon drawing listeners into an individual, culturally informed and humanistic experience of the song or story he is communicating, taking them on a journey of their own creation. Using a variety of techniques, he asks participants in his workshops to relate to songs and stories from as many angles as they are able to suggest, with the goal of becoming "multi-dimensional". [ Return to the article ]

14Sam Lee of Cecil Sharpe House in London, a singer heavily influenced by Stanley Robertson's approach, is the source of the following analogy which I think sums up very well how Travellers construct their identity. Another related aspect, which is not discussed here, is the association of Travellers with fortune telling and divination. [ Return to the article ]

15Stanley Robertson often compares the journeys of Travellers to "The Pilgrim's Progress". See Sharrock 1976. [ Return to the article ]

16EI 2006.069 (my italics) [ Return to the article ]

17EI 2005.061 Stanley Robertson frequently uses the local Scots vernacular, in this case, the North- East and Aberdeen dialect known as Doric. Traditional performance continues to make expressive use of multiple and widely spoken Scottish dialects. Many Travellers use their own combinations of Scots, Cant (Scottish Travellers "cover language"), Romani and Gaelic language in performance, song and storytelling. [ Return to the article ]

18EI 2005.061 Stanley Robertson emphasises that Travellers educated him through an inventive use of natural surroundings. Visual connections to ballad locations were used in particular to give a reference point on which to hinge and develop the context of songs and stories. [ Return to the article ]

19EI 2002.037 [ Return to the article ]

20EI 2002.037 [ Return to the article ]

21Bauman (1974, 41) refers to the use of kinesic markers as points of connection in folklore performance. [ Return to the article ]

22In Stanley's mind, this idea conveys a perceptive and intuitive ability to see, feel, and understand the essence of any situation. It is instigated through a methodology and process of connection that is intensely personal and involves an individual ability to relate to surroundings from the inside, using all senses to experience and express the event. [ Return to the article ]

23EI 2002.037

Wint (North-East Doric), went.

Yak (North-East Traveller Cant), eye.

Faur (North-East Traveller Cant), where.

Aa (North-East Doric), all.

Awa (North-East Doric), away.

Auld (Scots), old.

Caa (Scots), call.

Tae (Scots), to.

Wi (North-East Doric), with. [ Return to the article ]

24EI 2002.037 The spiritual dimensions accorded to this way of looking are important. Stanley Robertson has multiple teaching mechanisms with the same goal in mind. Each leads to a view of "pure intelligence", and suggests that the eye of the skull is a metaphor for progressive enlightenment. [ Return to the article ]

25EI 2002.037 [ Return to the article ]

26EI 2006.127 [ Return to the article ]

27EI 2002.037

Weel (North-East Doric), well.

Hae (North-East Doric), have.

Ye (Scots), you.

Oot (North-East Doric), out.

Mair frae gaun (North-East Doric), more from going.

Wid (North-East Doric), would. [ Return to the article ]

28Conversation with Stanley Robertson, Aberdeen, 2007. [ Return to the article ]

29EI 2007.116 [ Return to the article ]

30The latter category includes historic tales such as the legendary visits of the Gabelunzie King to Lumphanan. [ Return to the article ]

31EI 2007.128 [ Return to the article ]

32Video footage from the personal collection of Stanley Robertson.

Mither (North-East Doric), mother.

Long (North-East Doric), lang.

Wis (North-East Doric), was.

Bairns (North-East Doric), children.

Oors aa richt (North-East Doric), ours all right.

Twa hooses (North-East Doric), two houses.

Ging (North-East Doric), go.

Aye (North-East Doric), always. 'Aye' also means 'Yes' in Scots usage.

O (Scots), of. [ Return to the article ]

33Stanley has used a "ballad commonplace" phrase to describe this part of the road, one of many which is incorporated into his spoken language. [ Return to the article ]

34Video footage from the personal collection of Stanley Robertson.

Pairt (North-East Doric), part.

Fin (North-East Doric), when.

Wid (North-East Doric), would.

Cairt (North-East Doric), cart.

Tak (Scots), take.

Hoose (North-East Doric), house.

Aiberdeen (North-East Doric), Aberdeen.

Intae (North-East Doric), intae.

Lookit (North-East Doric), looked.

Glimmer (North-East Traveller Cant), fire.

Biling (North-East Doric), boiling.

Gunnel (North-East Doric), the very top.

Duke (North-East Doric), duck.

Sharras (North-East Traveller Cant), eggs.

Couldna (North-East Doric), couldn't. [ Return to the article ]

35These are Stanley's words of description, though they align well with the theories of Victor Turner on transformative spaces. See Turner 2002. [ Return to the article ]

36Wi yer (North-East Doric) with your [ Return to the article ]

37One effect of listening within these created spaces of narrative performance is a heightened experience that is "in concert" with the understandings of the performer. See Kapchan 2003, 134. [ Return to the article ]

38Stanley tells the following story about Tammy Toddle. "The story's aboot this wee mannie [man], he wis a wee hunchback. An ugly wee cratur [person]. And aabody in the toon [town], ye ken [you know], shunned him because o his appearance. He wis like a wee mountebank. But he went oot [out] to bide [live] in the country, and the wee fairy folk o the place looked at him and never seen him as ugly. They just seen him as one o them. And they accepted him. So, they kint [knew] the treatment he wis getting in the toon. So they built him a wee hoosie [house]. It wis the fairy folk that built him his wee hoosie". EI 2007.009 [ Return to the article ]

39(Robertson 2005)

Whin (Scots), when.

Nae (North-East Doric), not.

Jist (North-East Doric), just.

Intae (North-East Doric), into.

Fit (North-East Doric), what.

Gang (North-East Doric), go.

Winnae (Scots), won't.

Oot (North-East Doric), out.

Hunners (North-East Doric), hundreds.

Hinnie (Scots), then. [ Return to the article ]

40See note 63. [ Return to the article ]

41Stanley has used this expression as a themed title for some of his many educational workshops. [ Return to the article ]

42Stanley's family tradition states how the authorities of the time were reluctant to investigate the murder or provide an official burial for the dead woman. [ Return to the article ]

43Steven Webb has been a regular attendant at Stanley's workshops on creativity and storytelling. His visits to the old road with Stanley have inspired him to write several poems related to the Traveller history of Lumphanan using Stanley's methodology of going "through the eye of the skull". [ Return to the article ]

44EI 2007.104 [ Return to the article ]

45EI 2007.104 [ Return to the article ]

46EI 2007.104 [ Return to the article ]

47EI 2007.104 [ Return to the article ]

48EI 2004.037 [ Return to the article ]

49EI 2006.127 [ Return to the article ]

50EI 2006.127 [ Return to the article ]

51Hufford"s discussion of "official" and "unofficial" belief suggests how, in the absence of experience, willingness to believe is informed by context. [ Return to the article ]

52In performance, Stanley tells an anecdote which he attributes to Traveller Duncan Williamson. The many dialects of Scottish Traveller Cant which feature words derived from Scots, Gaelic and Romani have one common feature which relates to Cant's status as a primarily functional "cover language" designed to conceal the content of conversations from outsiders. Describing this function, Duncan would say, "If ye can't buy it, sell it, eat it, drink it or make love to it, there's no word for it in Cant". Stanley Robertson in performance at "The Gyspy Arts Festival", Edinburgh, 2008. [ Return to the article ]

53Conversation with Stanley Robertson, Aberdeen, 2007. [ Return to the article ]

54EI 2005.130 "Rest and be Thankful" is also a Scottish place-name for the summit of a steep mountain road in the Highlands of Scotland. [ Return to the article ]

55EI 2005.130 This physical and visual approach to learning in progressive steps, which Stanley Robertson describes as an ancient teaching method, is used by many Travellers in various educational settings and is noted for its effectiveness and contrast to conventional teaching. [ Return to the article ]

56EI 2005.130

Steen (North-East Doric), stone.

Doon (North-East Doric), down.

Faur (North-East Doric), where.

Fae (North-East Doric), from.

The 'ie' ending represents the diminutive in North-East Doric. Steenies are small stones.

Whaur (Scots), where. [ Return to the article ]

57A description of Travellers given by Stanley Robertson in performance at "The Travellers' Day", Aberdeen, 2006. [ Return to the article ]

58Stanley Robertson often picks this theme for focus in his teaching work. [ Return to the article ]

59Stanley Robertson in performance at "The Travellers' Day", Aberdeen, 2006. [ Return to the article ]

60Stanley Robertson's vast repertoire of naturally descriptive ballads includes "Up a Wild and Lonely Glen", a song which reminds him of his father"s singing at Lumphanan.

"Up a wild and lonely glen

Shaded by mony [many] a purple mountain

Twas far from the busy haunts o men

The first time that I gaed [went] oot a hunting"

This beautiful ballad, which Stanley visually associates with the singing of his father William Robertson at Lumphanan, is a version of the song "Queen Among the Heather", sung in different distinct versions by many Travelling families. [ Return to the article ]

61The Tree of Life stands near the heart of the Old Road and became a gauge of personal progress. Stanley remembers how, as children, they would measure their height year by year standing against this tree. [ Return to the article ]

62EI2007.097 [ Return to the article ]

63This phrase is used by Stanley Robertson in his poem "Exodus o Travellers". [ Return to the article ]

64Conversation with Stanley Robertson, Aberdeen, 2006. [ Return to the article ]

65Conversation with Stanley Robertson, Aberdeen, 2007. [ Return to the article ]

66"Cruvie" is a Scots derivative of the Gaelic word "craobh" meaning "tree." Auld Cruvie is the most prominent tree on the heart of the old road. "His" traditionalised association with wisdom is connected to "his" longevity, and "he" stands as a symbol of timelessness and renewal. The transformational experiences, rather like "rites of passage", through which the structures of Jack tales are developed is an important theme. Stanley notes that there are leagues of growth within the Jack tales, making them suitable for application to every stage of life. As a young shepherd boy, who spent most of his life under Auld Cruvie, Jack grew up immersed in nature and so learns to interact with and understand the language of the elements. [ Return to the article ]

67Conversation with Stanley Robertson, Aberdeen, 2007. [ Return to the article ]

68Conversation with Stanley Robertson, Aberdeen, 2007. [ Return to the article ]

69Unindexed interview with Stanley Robertson, 19.10.08. [ Return to the article ]

70EI 2002.085 [ Return to the article ]

71Conversation with Marc Ellington, Aberdeen, 2006. [ Return to the article ]

72A bridal path in Traveller tradition is a road which when walked by a courting couple results in them being married on reaching the end of the road. Again, this idea aligns well with the progressive idea of journey as a rite of passage. [ Return to the article ]

73In verse four Stanley Robertson draws attention to the uncharacteristic "marching" of the shepherds as an omen for ensuing war and its effects of breaking up established families, courtships and social and domestic structures. Stanley Robertson in performance, Aberdeen, 2007. [ Return to the article ]

74Conversation with Stanley Robertson and his son Anthony Robertson whilst crossing Glenshee on a drive around some Scottish ballad locations, 2008. [ Return to the article ]

75Stanley Robertson, Unindexed interview on "Ballads and Creativity", Aberdeen, March 2008. [ Return to the article ]

76Stanley Robertson, Unindexed interview on "Ballads and Creativity", Aberdeen, March 2008. [ Return to the article ]

77Stanley Robertson, Unindexed interview on "Ballads and Creativity", Aberdeen, March 2008. [ Return to the article ]

78Stanley Robertson, Unindexed interview on "Ballads and Creativity", Aberdeen, March 2008. [ Return to the article ]

79Stanley Robertson in a workshop for "Scottish Culture and Traditions", Aberdeen, 2007. [ Return to the article ]

80Titon. 1997, 94 [ Return to the article ]

81Stanley Robertson, Unindexed interview on "Ballads and Creativity", Aberdeen, March 2008. [ Return to the article ]

82Stanley Robertson, Unindexed interview on "Ballads and Creativity", Aberdeen, March 2008. [ Return to the article ]

83Stanley Robertson, Unindexed interview on "Ballads and Creativity", Aberdeen, March 2008. [ Return to the article ]

84Stanley Robertson, Unindexed interview on "Ballads and Creativity", Aberdeen, March 2008. [ Return to the article ]

85Stanley Robertson, Unindexed interview on "Ballads and Creativity", Aberdeen, March 2008. [ Return to the article ]

86Stanley Robertson, Unindexed interview on "Ballads and Creativity", Aberdeen, March 2008. [ Return to the article ]

87Interview by Fiona-Jane Brown with Stanley Robertson on behalf of Grampian Association of Storytellers, Elphinstone Institute, 2006. http://www.GAS.co.uk accessed 21.11.2007. [ Return to the article ]

88EI 2007.112 [ Return to the article ]

89EI2005.130 "The Mysie", is a term unique to Stanley Robertson's family. He describes it as a corruption of the English language term "The Muse". Other Travellers such as Sheila Stewart use the expression "The Coinyach" to describe this phenomenon. [ Return to the article ]

90Jeannie Robertson was renowned for this ability. [ Return to the article ]

91Stanley Robertson's description conjoins with his traditional and spiritual belief that when the presence of God is felt, it travels down the spine and when it comes from the devil "shivers" are felt up the spine. [ Return to the article ]

92Stanley Robertson, Unindexed interview on "Ballads and Creativity", Aberdeen, March 2008. [ Return to the article ]

93Midden (North-East Doric), rubbish dump. [ Return to the article ]

94Stanley Robertson often takes visitors to this spot below the main camping ground and encourages them to dig. He delights in its possibility to continually divulge new artefacts, and often uses it to illustrate the strict codes of cleanliness and hygiene observed by his people. [ Return to the article ]

95Stanley Robertson's ability to invent stories from symbols became fully apparent to me when he one day told a story of epic potential based upon the mass produced and, in my mind, unremarkable images of beans printed on a disposable paper coffee cup. [ Return to the article ]

Works Cited

Abrahams, Roger D. 2003. Identity. In Eight Words for the Study of Expressive Culture, edited by Burt Feintuch, 198-222. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Basso, Keith H. 1996. Wisdom Sits in Places: Notes on a Western Apache Landscape. In Senses of Place, edited by Steven Feld and Keith H. Basso, 53-90. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press.

Bauman, Richard. 1971. Differential Identity and the Social Base of Folklore. In Towards New Perspectives in Folklore. Américo Paredes and Richard Bauman eds. Journal of American Folklore 84.

Ben-Amos, Dan. 1999. Afterword. In Cultural Memory and the Construction of Identity, edited by Dan Ben-Amos and Liliane Weissberg. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Braid, Donald. 1996. Personal Narrative and Experiential Meaning. The Journal of American Folklore 109: 5-30.

Buchan, David. 1997. The Ballad and the Folk. East Linton: Tuckwell Press.

Clayton, Martin. 2001. Introduction: Towards a Theory of Musical Meaning (in India and Elsewhere). British Journal of Ethnomusicology 10: 1-17.

Daniels, Stephen, and Catherine Nash. 2004. Lifepaths: Geography and Biography. Journal of Historical Geography 30: 449-58.

Davies, Owen. 2007. The Haunted: A Social History of Ghosts. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Douglas, Sheila. 2007. Narrative in Traveller Scotland. In A Compendium of Scottish Ethnology: Scottish Life and Society, Oral Literature and Performance Culture 10: 213-24.

Edwards, Emily D. 2001. A House That Tries to Be Haunted: Ghostly Narratives in Film and Popular Television. In Hauntings and Poltergeists: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, edited by James Houran and Rense Lange, 82-120. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

Goldstein, Kenneth S. 1972. On the Application of the Concepts of Active and Inactive Traditions to the Study of Repertoire. In Towards New Perspectives in Folklore, edited by Americo Parédes and Richard Bauman, 80-86. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Glassie, Henry. 1994. The Practice and Purpose of History. The Journal of American History 81: 961-68.

Henderson, Hamish. 2004. Alias Macalias, Writings on Songs, Folk and Literature. 2nd edition. Edited by Alec Finlay. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

_____. 1981. The Tinkers. In A Companion to Scottish Culture, edited by David Daiches, 377-78. London: Edward Arnold.

Higgins, Lizzie. 2006. In Memory of Lizzie Higgins. Musical Traditions Records MTCD337-8.

Hufford, David J. 1995. Beings without Bodies: An Experience-Centered Theory of the Belief in Spirits. In Out of the Ordinary, edited by Barbara Walker, 11-45. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Ingold, Tim. 1993. The Temporality of the Landscape. World Archaeology 25:152-74.

Kapchan, Deborah A. 2003. Performance. In Eight Words for the Study of Expressive Culture, edited by Burt Feintuch, 121-145. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Kenrick, Donald, and Colin Clark. 1999. Moving On: The Gypsies and Travellers of Britain. Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press.