Freud's Psychoanalytic Theory

Classical psychometry confronted a crisis when it was realized that behavior is not as consistent, across time or across context, as the Doctrine of Traits led people to expect. People could be friendly one moment and hostile the next, conscientious in one situation and irresponsible in another. In response to this empirical failure, many trait theorists sought to shore up the Doctrine by aggregating responses across time and context, employing multivariate prediction models, and the like. Another response to the problem of apparent inconsistency was to argue that consistency lay beneath the surface of behavior, in mental processes which were largely invisible, and which could be revealed only by painstaking analysis.

Psychoanalysis is part of a larger movement known as depth psychology, which argues that the most important aspects of personality lie below the level of conscious introspection, and are not visible to whose who confine their observations to superficial features of social behavior. All depth psychologies make use of the iceberg metaphor: just as only one-ninth of an iceberg is visible above the surface of the ocean, so only a small portion of personality is apparent in what people do, and think, in the ordinary course of everyday living. People are not aware of, or at least cannot articulate, the reasons for their own behavior. For this reason, overt behavior of the type assessed by trait psychologists is of little interest -- the more appropriate focus is on what lies below.

Although we present psychoanalysis as an alternative to trait psychology, in historical terms the two approaches developed contemporaneously and largely in isolation from each other. Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, lived from 1856 to 1939. Wilhelm Wundt, who drew attention to continuous distributions underlying the classic fourfold typology, lived from 1832 to 1920; Charles Spearman, who developed the correlational techniques that formed the backbone of the individual-differences movement, lived from 1863 to 1945. In other ways, too, depth psychology was not a direct challenge to trait psychology. Depth psychology developed primarily within Viennese and Swiss medical circles, which were largely ignorant of the trends in trait psychology, which was largely centered in London and the United States. At the turn of the century, Vienna and London were different on almost every conceivable dimension [cite here the work on fin de siecle Vienna]. In psychology this difference was apparent in the difference between psychometrics and psychoanalysis; in fine art, it was reflected in the difference between representationism and expressionism. Many British (and French) artists of the period were interested in painting the world as it really was; by contrast, the artists of Germany and the Austro-Hungarian empire were interested in portraying their own emotional responses to scenes and events, and in eliciting affective reactions from viewers. So, to, in personality: the British were interested in describing the differences between people; the Viennese were interested in uncovering the hidden, primitive emotions that everyone shares.

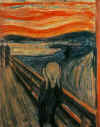

| The German Expressionists included the members of Die Brucke ("The Bridge), led by Ernst Kirchner, and including Erich Heckel and , Emil Nolde, and the members of Der Blaue Reiter ("The Blue Rider"), a movement led by Wassili Kandinsky and Franz Marc. The painting is obviously The Scream (1893) by Edvard Munch -- who, as a Norwegian, wasn't technically a German Expressionist. But he was still an Expressionist, and the painting captures the spirit of the movement and the time. |

Sources of Freud's Insight

Whereas trait psychology

developed as a collective product of many investigators,

psychoanalysis is largely the product of one mind: Sigmund

Freud. His ideas were not wholly original: some of his most

central concepts had been popular in philosophy, psychology,

and medicine for years. Building on this tradition, however,

Freud's inspiration came both from his work in the clinic

and his observation of the everyday world about him.

Whereas trait psychology

developed as a collective product of many investigators,

psychoanalysis is largely the product of one mind: Sigmund

Freud. His ideas were not wholly original: some of his most

central concepts had been popular in philosophy, psychology,

and medicine for years. Building on this tradition, however,

Freud's inspiration came both from his work in the clinic

and his observation of the everyday world about him.

The First Dynamic Psychology

It is commonly thought that the concept of unnconscious mental processes, and of the psychological causation of mental illness, both trace their origins to Freud and his theory of psychoanalysis. To the contrary, both ideas have a long and distinguished history before Freud (Ellenberger, 1970; Hilgard, 1973; Klein, 1977; Whyte, 1960). The introduction of these ideas into scientific medicine began around 1775, with appearance of Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-1815). Mesmer had taken his medical degree in 1775 at the University of Vienna, already the world's premier medical school, with a dissertation entitled On the Influence of the Planets on the Human Body. In it, he argued that, just as gravitational forces affected the earth, in the form of tides and magnetism, so to they could affect the physical body.

Mesmer was no crackpot astrologer. The scientific community of the 18th century Enlightenment was fascinated by the phenomenon of action at a distance -- the idea that objects could affect each other without being in direct contact. The two clearest examples of this principle were gravity (exemplified, in the apocryphal tale of Newton, by the attraction of the earth for an apple on a tree) and tides (the effect of the sun and moon on terrestrial seas). Mesmer thought that the heavenly bodies could affect people as well. But, more important, he argued that people could affect people in a similar way. According to his theory, disease was caused by an improper distribution of magnetic fluid (force) in the patient's body, with the locus of the disease corresponding to the locus of the surplus or deficit. Following the customary practice of his time, he originally treated the sick by applying magnets to their bodies, in the hope of rectifying the inappropriate distribution of magnetic fluids. Eventually, he discovered that magnets were not necessary for therapeutic success. By pointing an iron wand at the patient, and later by passing his hands over (but not touching) the afflicted area, Mesmer found that he could precipitate convulsive seizures resembling those of grand mal epilepsy. When the patients recovered from these crises, as Mesmer called them, they appeared to be cured of their ailments. Mesmer held strongly to the theory of action at a distance, mediated by invisible forces. But because magnets were not necessary, he argued that he had discovered a new force,animal magnetism -- the force by which one individual could affect another.

Although Mesmer's theory sounds wild, in practice he was successful in curing many patients whose afflictions had stymied other practitioners. He moved from Vienna to Paris, where he set up a practice patronized by many members of the court of King Louis XVI. But Mesmer was not in business just for the money. He treated many peasants free of charge by "magnetizing" a tree in the village square (for example), which the ill would touch, often to fall into a crisis and awaken cured. And he also developed the first group therapy. A number of patients would sit around a bacquet, a tub filled with water and iron filings, grasping protruding rods. Musicians would play softly in the darkened room, and after some buildup of tension Mesmer would enter the room dressed in a purple suit and cloak, and make passes with his hands over the tub. At this point many patients would fall into crises, and, again, awaken relieved of their symptoms.

The success of Mesmer's technique, not to mention his success at attracting clientele from among the ladies of the royal court, prompted King Louis to appoint a commission to investigate him in 1784. The members of the Royal Commission included two distinguished French scientists, Lavoisier and Guillotin, and was chaired by Benjamin Franklin, then serving as ambassador for the newly founded United States of America. (There was also another commission, appointed by the French Academy of Sciences). Mesmer would not permit himself to be investigated, and so the Franklin commission turned its inquiry to one of his disciples, Georges Debeouf.

In the course of their work they conducted what may well stand as the earliest controlled psychological experiments. In one, Debeouf was asked to magnetize one of a stand of trees, and then a patient, known to be susceptible to the effects of animal magnetism, was asked to walk through the grove, passing near each tree in turn. Nothing happened when he passed the tree that had been magnetized. But upon reaching the last one, the patient promptly fell into a crisis. In another, a susceptible patient and a mesmerist were placed in adjoining rooms, separated by a curtain. When the mesmerist made magnetic passes unbeknownst to the patient, nothing happened; but when she was told that he was making his passes, although he was actually doing nothing at the time, she fell into a crisis. The Franklin Commission concluded that Mesmer's cures were genuine, but his theory was wrong. The crises were the product of "imagination" rather than of physical forces. Thus placed outside the realm of Enlightenment science, which had no room for topics such as imagination, Mesmer left Paris and eventually died in Switzerland (for biographies, see Buranelli, ref; Darnton, ref; Pattie, 1993; Shore & Orne, 1965; Tinterow, 1970).

Mesmerism itself did not die, however. The practices were maintained by a small cult that had some impact on political events by virtue of its association with Freemasonry (Darnton, ref). The classic mesmeric convulsions had disappeared from sight after the discovery by the Abbe Faria of the "perfect crisis", in which the patient fell into a sleeplike state. The technique of mesmerism was the common stuff of charlatans and travelling stage shows: Mark Twain (ref) offers an amusing account of one. However, it was also revived twice as part of scientific medicine.

A number of physicians, notably Braid (ref) and Esdaille (ref), employed the technique to induce anesthesia before surgery. Braid coined the term hypnotism for the procedure, after the Greek word for sleep. But the introduction of chloroform and other chemical anesthetics, which were both more reliable and more acceptable to the materialist world view of the scientific establishment, led quickly to its demise.

Later, the technique was rediscovered by Jean-Marie Charcot (1825-1893) and Hippolyte Bernheim (1840-1919) as a cure for hysteria, syndromes that mimicked the symptoms of physical disease but for which no organic cause could be found. For example, a patient might complain of deafness, but no defect could be detected in his auditory system, and subtle tests clearly indicated that he was actually processing auditory information despite his denial. Similarly, a woman might complain of glove anesthesia -- a lack of feeling in the hand and wrist -- despite the fact that such an experience is physiologically impossible given the distribution of the peripheral nerves. These symptoms all seemed to reflect a change in consciousness, as percepts, memories, thoughts, and actions occurred outside the individual's phenomenal awareness and voluntary control.

Interestingly, similar phenomena could be induced by means of hypnotic suggestion. This suggested to Charcot that hypnotizable individuals shared the same underlying pathology as hysterics -- an assumption that has since been disproved by a wealth of evidence which shows that hypnotizable people are quite normal (J. Hilgard, 1979). Bernheim, on the other hand, concluded that hysteria, like hypnosis, was a product of psychological processes. In any event, both Charcot and Bernheim, along with their followers, agreed that the phenomena represented, at some level, the power of ideas to turn into actions. This is one of the meanings of the term dynamic in the psychological sense. Thus was born the First Dynamic Psychiatry and the emergence of psychogenic rather than somatogenic theories of the etiology of mental illness.

As a student and young professional, Freud studied with both Charcot and Bernheim. He translated their works into German, and wrote favorable articles describing their work. He began a successful clinical practice using hypnosis to cure hysteria, but he soon discovered that it was not enough merely to suggest the symptoms away. Pierre Janet (1859-1947) and Morton Prince (1854-1929), among others, continued to promote the theories of the First Dynamic Psychiatry. In fact, Prince founded the Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, which as the Journal of Abnormal Psychology has remained the world's most important journal for research on psychopathology. However, Freud himself quickly moved away to develop his own theory. Conflict arose between the First Dynamic Psychiatry and the New Dynamic Psychiatry (the terms are due to Ellenberger, 1970). Janet was invited to lecture at Harvard largely at the instigation of Prince and James; Freud, lacking an inside contact, lectured at the newly founded Clark University, outside Boston. Eventually psychoanalysis came to dominate the field (leading to many editorial complaints by Prince in his journal), although recently the theory of dissociation has been revived (Hilgard, 1977; Kihlstrom, 1984). But the First Dynamic Psychiatry had convinced Freud that the psychogenic theory was correct, and that the psychological causes of mental illness lay in mental states that were outside our awareness and free of our control.

The psychogenic theory was developed by Charcot's pupil and successor Pierre Janet and by Morton Prince, an American psychologist who founded the psychological clinic at Harvard. Janet argued that the elementary structures of the mind were psychological automatisms: complex acts, tuned to environmental demands and personal goals, which were preceded by an idea and accompanied by an emotion. Each of these psychological automatisms, by combining thought, emotion, motivation, and action, represented a kind of rudimentary primitive consciousness. In normal people, according to Janet, all of these automatisms were bound together into a single, unified stream of consciousness, operating in awareness and under voluntary control. Under certain circumstances, however, one or more of these automatisms could be split off -- Janet's term was disaggregation, Prince's dissociation -- from the rest, functioning outside of awareness, voluntary control, or both. This view of the mind was further elaborated by Prince. He referred to dissociated mental activity as co- conscious (if the simultaneous streams were both performed in consciousness) or subconscious (if one or more streams were outside awareness) rather than unconscious, because this last term seemed to connote a lack of mental activity.

Studies on Hysteria

Freud was initially trained as a neurologist, and he distinguished himself in both neuroanatomy and neurosurgery, and did research on aphasia and the effects of cocaine. However, the young Freud was first and foremost a clinical practitioner interested in the problems of individual patients. It was this concern that led him to study with Charcot and Bernheim in France, where the study of hysteria was well advanced. Although drawn at first toward Charcot and his somatogenic theorizing, Freud eventually sided with Bernheim and those members of the First Dynamic Psychiatry who were attempting to develop a psychogenic account of these mysterious syndromes. Following his postgraduate studies Freud returned to Vienna and set up a practice with a more senior physician, Joseph Breuer, specializing in the treatment of hysteria. Following Bernheim's lead, Breuer and Freud began by treating hysteria with direct hypnotic suggestion -- more or less suggesting that the symptoms would disappear. However, they gradually abandoned hypnosis, in part because not all of their patients were hypnotizable, and in part because they stumbled on a new technique, called the cathartic method, which appeared to be more reliable (for an historical account of Freud's interest in hypnosis, see Kline, ref). The case that marked the shift from hypnosis to catharsis was that of Bertha Pappenheim, who later became a famous German social worker, but who was known in the Studies merely as Anna O.

Anna O. had a normal childhood and

adolescence, and was known as a healthy, intelligent young

woman. At the age of 21, however, she fell ill and

manifested classic symptoms of hysteria. While nursing her

dying father she became weak, anorectic, and anemic, with a

chronic headache and squinting eyes. She complained of

hallucinations of snakes and falling walls, paralysis of the

neck and extremities, and anesthesia in the extremities. Her

family reported periods in which she would become

irresponsible and antisocial, for which she later had no

memory. She would also occasionally show loss of speech,

followed by a period in which she could speak English but

not her native German.

Anna O. had a normal childhood and

adolescence, and was known as a healthy, intelligent young

woman. At the age of 21, however, she fell ill and

manifested classic symptoms of hysteria. While nursing her

dying father she became weak, anorectic, and anemic, with a

chronic headache and squinting eyes. She complained of

hallucinations of snakes and falling walls, paralysis of the

neck and extremities, and anesthesia in the extremities. Her

family reported periods in which she would become

irresponsible and antisocial, for which she later had no

memory. She would also occasionally show loss of speech,

followed by a period in which she could speak English but

not her native German.

Breuer first treated Anna O. with direct hypnotic suggestion. When this strategy failed, he coaxed her to talk about her symptoms while she was hypnotized. As she talked, it became apparent that the manifest symptoms of her illness had been anticipated by earlier events -- memories of which were not available to her in the normal waking state. Breuer noted, remarkably, that symptoms disappeared when she described the circumstances under which they first appeared. However, they returned when she was not hypnotized.

Eventually, the origin of her hysteria became clear. While keeping a deathwatch over her father, she heard the sounds of a neighbor's party and felt guilty for wanting to join in the fun. She dozed off with her right arm over the back of the chair, and had a dream in which her father was attached by a black snake. Awaking in a panic, she found that her right arm had "fallen asleep", rendering her unable to defend him. Not realizing that she had been dreaming, she became very frightened and tried to pray. But in her confusion all she could bring to mind were some English nursery-rhymes. When she remembered this event, the symptoms disappeared completely. Anna O., whose real name was Bertha Pappenheim, went on to a distinguished career as a social worker and militant feminist (cite biography).

In their joint work,Studies on Hysteria, Breuer and Freud (1893- 1895) reported a series of cases, including Anna O. and four others. Each of these yielded similar findings. In each case, the hysterical symptoms disappeared when the event evoking them was recalled, along with the affective experience which initially accompanied it. This emotional reliving of a forgotten event, called abreaction, lies at the heart of the cathartic method. Later clinical investigation revealed that hypnosis was not necessary for the success of the procedure. Freud replaced hypnosis with the method of free association, in which the patient reports whatever is on his or her mind. Beginning with a symptom, dream, childhood memory, or any other material, Freud found that patients would eventually uncover for themselves the decisive traumatic event.

From this kind of clinical investigation, Breuer and Freud concluded that "hysterics suffer from reminiscences" (ref). More generally, they asserted that all of us are affected by ideas and memories of which we are not directly aware. Moreover, there appears to be a "force" preventing them from becoming conscious. That force must be overcome in order to reveal the unconscious thought or memory that, in psychodynamic terms, is the ultimate cause of mental illness.

The Interpretation of Dreams

Breuer and Freud dissolved their professional association after their work on hysteria, in part after a disagreement over Breuer's treatment of a patient. Five years later, Freud published what he himself regarded as his most important work,The Interpretation of Dreams (Freud, 1900). The book begins by reviewing the scientific literature on dreams available at the turn of the century -- a literature that is surprisingly large. For example, it was known that we can remember things in dreams that we cannot remember while awake, and that we often forget our dreams soon after awakening. Moreover, the mental life of the sleeper appeared to be quite different from that of waking consciousness. Dreams were full of rich and vivid sensory images and appear involuntary, while normal thought is deliberate and commonly based on language. These and other observations raised the question of the nature of dreams, and whether they have any adaptive purpose.

The bulk of the book contains Freud's attempt to uncover the meanings of his own dreams by means of the technique of free association. He began with "The Dream of Irma's Injection". Irma was both a family friend and a patient, a woman with symptoms of hysteria ("Irma" was a pseudonym for Emma Eckstein, who later became a psychoanalyst herself). Freud had applied his new psychoanalytic method to her, and she had shown some improvement. However, this strategy and its outcome were criticized by Otto, Freud's friend and junior colleague. Freud resolved to defend himself by documenting her case and submitting his report to Dr. M., their senior colleague, for his evaluation. During this period, Freud had the following dream.

A large hall -- numerous guests, whom we were receiving. -- Among them was Irma. I at once took her on one side, as though to answer her letter and to reproach her for not having accepted my "solution" yet. I said to her: "If you still get pains, it's really only your fault". She replied: "If you only knew what pains I've got now in my throat and stomach and abdomen -- it's choking me" -- I was alarmed and looked at her. She looked pale and puffy. I thought to myself that after all I must be missing some organic trouble. I took her to the window and looked down her throat, and she showed signs of recalcitrance, like women with artificial dentures. I thought to myself that there was really no need for her to do that. -- She then opened her mouth properly and on the right I found a big white patch; at another place I saw extensive whitish grey scabs upon some remarkable curly structures which were evidently modeled on the turbinal bones of the nose. -- I at once called in Dr. M., and he repeated the examination and confirmed it.... Dr. M. looked quite different from usual; he was very pale, he walked with a limp and his chin was clean-shaven.... My friend Otto was now standing beside her as well, and my friend Leopold was percussing her through her bodice and saying: "she has a dull area low down on the left". He also indicated that a portion of the skin on the left shoulder was infiltrated. (I noticed this, just as he did, in spite of her dress.)... M. said: "There's no doubt it's an infection, but no matter; dysentery will supervene and the toxin will be eliminated." ... We were directly aware, too, of the origin of the infection. Not long before, when she was feeling unwell, my friend Otto had given her an injection of a preparation of propyl, propyls ... propionic acid ... trimethylamin (and I saw before me the formula for this printed in heavy type).... Injections of that sort ought not to be made so thoughtlessly.... And probably the syringe had not been clean.

Freud's interpretation began by identifying certain day residues, aspects of the dream that were clearly related to recent events. Irma, Otto, and Dr. M. are obvious examples. Moreover, Freud and Irma happened to be vacationing at the same resort at the time, and Irma was to be a guest at a forthcoming party. (Most of Freud's patients were drawn from the upper strata of Viennese society, and it was remarkably common for physicians and their patients to move in the same social circles.) Wilhelm Fleiss, one of Freud's friends, had the theory that trimethylamine was a byproduct of sexual activity. Irma was a young widow, and Freud had suggested that her mental illness was caused by problems of a sexual nature. With these and other considerations in mind, the meaning of the dream was quite clear to Freud. Otto, not Freud, was responsible for Irma's continuing illness. His skepticism prevented her from becoming fully involved in her treatment, abreacting, and achieving a complete cure. In the dream, Freud's diagnosis was confirmed not only by the impartial Dr. M., but also by Otto's brother Leopold! Thus, the dream represented Freud's much-desired revenge on his colleague.

Making the same point, Freud (1900, pp.) reports the following dream by his 19-month-old daughter, Anna, who was later to make her own distinguished contributions to psychoanalysis. The story gains something in translation, and the reader should imagine the child using the equivalent of German baby-talk.

My youngest daughter ... had had an attack of vomiting one morning and had consequently been kept without food all day. During the night after this day of starvation she was heard calling out excitedly in her sleep: Anna Fweud, stwabewwies, wild stwawbewwies, omblet, pudden!" At that time she was in the habit of using her own name to express the idea of taking possession of something. The menu included pretty well everything that must have seemed to her to make up a desirable meal.

Analyses of other dreams led to similar conclusions. For Freud, dreams represented the fulfillment of wishes, though in fantasy rather than reality. Often the wish is transparent, as in Freud's dream of Irma and Anna's dream of food. At other times, however, the wish is hidden by distortions, displacements, and symbolic transformations. Therefore, the manifest content of the dream, its surface appearance, must be interpreted to uncover its latent content, or hidden meaning. In such cases, Freud thought, the meaning is hidden because it arouses anxiety. The analysis of dream symbolism, then, suggested that there were other mental forces at work besides those which prevented unpleasant memories from becoming conscious. These additional forces disguised the true meaning and significance of ideas that were conscious.

The Psychopathology of Everyday Life

Just a year later, Freud published another of his most popular books,The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (Freud, 1901). The topic of the piece was the psychology of errors, what have since come to be called "Freudian slips". Such lapses are a common occurrence: all of us have stumbled over the name of someone we knew quite well, or a foreign word or phrase; all of us have made slips of the tongue, or pen, or typewriter. One often encounters the forgetting of impressions, as when a friend walks out of the cinema and cannot say what the film was al bout; or of intentions, as expressed by the familiar complaint, "I forgot what I was about to say". Freud drew attention to errors in memory as well as in action, especially the phenomenon of screen memory: despite all that has occurred in the first five or six years of our lives, all that is preserved -- for most of us -- are a few fragments of utterly banal events, without any apparent significance or emotional involvement attached to them. Up until Freud's time, the general consensus was that these sorts of phenomena were of a random nature, merely reflecting the vicissitudes of mental functioning. Freud thought differently, as illustrated by his story of "The AliquisEpisode".

Last summer... I renewed my acquaintance with a certain young man of academic background. I soon found that he was familiar with some of my psychological publications. We had fallen into conversation... about the social status of the race to which we both belonged; and ambitious feelings prompted him to give vent to a regret that his generation was doomed (as he expressed it) to atrophy, and could not develop its talents or satisfy its needs. He ended a speech of impassioned fervour with the well-known line of Virgil's in which the unhappy Dido commits to posterity her vengeance on Aeneas: "Exoriare..." Or rather, he wanted to end it in this way, for he could not get hold of the quotation and tried to conceal an obvious gap in what he remembered by changing the order of the words: "Exoriar(e) ex nostris ossibus ultor." At last he said irritably: "Please don't look so scornful: you seem as if you were gloating over my embarrassment. Why not help me? There's something missing in the line; how does the whole thing really go? "I'll help you with pleasure", I replied, and gave the quotation in its correct form: "Exoriar(e) ALIQUIS nostris ex ossibus ultor" [Let someone arise from my bones as an avenger].

"How stupid to forget a word like that!. By the way, you claim that one never forgets a thing without some reason. I should be very curious to learn how I came to forget the indefinite pronoun "aliquis" in this case."

I took up the challenge most readily, for I was hoping for a contribution to my collection.

There ensued the following train of free-associations:

The words aliquis, a liquis, reliquen,liquefying,fluidity,fluid.

Simon of Trent, whose relics the young man had seen.

The accusation that Jews engaged in ritual blood- sacrifice.

An article he had recently read in an Italian newspaper, on St. Augustine's views on women.

An old man named Benedict.

A series of Christian saints and church fathers: St. Simon, St. Augustine, St. Benedict, Origen.

St. Januarius, whose blood is kept in a reliquary in a church at Naples. According to legend, it liquifies on a particular day, and there is great turmoil if the miracle does not occur. Once, when the town was subject to military occupation, the commander threatened the parish priest with dire consequences if the miracle did not take place on schedule, which it did.

Finally, the man came to the end of his story:

"Well, something has come into my mind... but it's too intimate to pass on... Besides, I don't see any connection, or any necessity for saying it."

"You can leave the connection to me. Of course, I can't force you to talk about something that you find distasteful; but then you mustn't insist on learning from me how you came to forget youraliquis."

"Really? Is that what you think? Well, then, I've suddenly thought of a lady from whom I might easily hear a piece of news that would me very awkward for both of us."

"That her periods have stopped?

"How could you guess that?"

"That's not difficult any longer; you've prepared the way sufficiently. Think of the calendar saints [Januarius and Augustine], the blood that starts to flow on a particular day, the disturbance when the event fails to take place, the open threats that the miracle must be vouchsafed, or else.... In fact, you've made use of the miracle of St. Januarius to manufacture a brilliant allusion to women's periods.... You need only recall the division you made into a-liquis, and your associations:relics, liquefying, fluid. St. Simon was sacrificed as a child -- shall I go on and show how he comes in...?

"No, I'd much rather you didn't. I hope you don't take these thoughts of mine too seriously, if indeed I really had them. In return I will confess to you that the lade is Italian and that I went to Naples with her. But mayn't all this just be a matter of chance?

What is important here is the apparent fact that the omitted word, far from being randomly selected, was plausibly associated with an unpleasant topic that was very much on the mind of Freud's companion, and which he would much rather have forgotten. From this an many similar fascinating episodes, documented in the book and in the Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis (Freud, 1916-1917), Freud concluded that our errors and lapses in thought and action are meaningful. Put briefly, in each case the target of the error was associated with some topic that evoked anxiety, and which had been forcibly put out of mind. According to the theory, the mechanism which rendered threatening material unconscious also acted on related, but innocent, material. This material, therefore, was either suppressed entirely or distorted beyond recognition.

Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious

In correspondence concerning drafts of the dream book, Freud's friend and colleague Wilhelm Fliess remarked that dreams were full of jokes. This led Freud to attempt an analysis of the psychology of humor. In discussing this book, we should warn the reader that Freud's sense of humor was quite different from what is commonly accepted today. It was full of puns, plays on words, and double-entendres, and the German word which is translated as "jokes" in the Standard Edition of Freud's works is probably better rendered as wit. Freud begins his treatise with an analysis of his favorite joke.

In the part of his Reisebilder entitled "The Baths of Lucca", the German poet Heine introduces the character of Hirsch-Hyacinth of Hamburg, who makes a living as a lottery-agent and extractor of corns from people's feet. At one point, Hirsch-Hyacinth boasts to Heine of his acquaintance with Baron Rothschild, one of the wealthiest men in Europe. At the end of his story, Hirsch-Hyacinth says,

"And, as true as God shall grant me all good things, Doctor, I sat beside Salamon Rothschild and he treated me quite as his equal -- quite famillionairely."

The joke probably loses something in translation, but its meaning is clear. The manifest story is that a rich man treated a poor man as his equal. However, this was an act of condescension on the part of Rothschild, and not an entirely pleasant experience for Hirsch-Hyacinth. Freud wanted to know what made the joke funny (as it was to Freud), when the underlying meaning is not. The humor arose from certain transformations applied to the raw material, chiefly abbreviation and condensation. Freud says that the joke actually represents two different thoughts: "He treated me familiarly" and "He treated me the way a millionaire would". In the punchline, a word is coined which stands for both.

FAMILI AR

MILIONAR

FAMILIONAR

FAMILIAR stands for the first thought; MILIONAR stands for the second; FAMILIONAR stands for them both. However, the punch line has to be analyzed to extract the underlying meanings. In doing so, the audience "gets" the joke.

Classical Psychoanalysis

From experiences, anecdotes, and analyses such as these, Freud derived the insight that we do not necessarily know why we do what we do, and that behavior may have a deeper significance that its surface appearance might suggest. This deeper meaning is rooted in conflicts concerning ideas and impulses which are typically sexual in nature. These sorts of conflicts produce anxiety, leading the person to defend himself against this "mental pain" by rendering the conflictual ideas and impulses unconscious. Nevertheless, Freud held, these unconscious ideas and impulses continue to strive for expression, and may actually be expressed in disguised form, as in dreams and errors of commission and substitution. This defensive mechanism also acts on innocent material which is associated with the conflict-laden material, as in errors of omission. This en masse suppression helps to keep the offending material from slipping into subjective awareness and voluntary action.

All of this was apparent to Freud by 1901 -- he wrote the book on jokes simply to illustrate his points about mental life in a different way, and to show how psychoanalysis could answer a frequent but puzzling psychological question: what makes a joke a joke? For the next 38 years he worked these insights into a comprehensive theory of the mind which made special reference to personality and sociocultural factors. The theory was roundly criticized in academic circles. But it was also widely endorsed, especially by artists and writers, so that it has come to dominate every aspect of modern culture. As we begin our examination of what the theory actually says, we wish to caution the reader that Freud continuously revised and reworded his ideas right up until his death, so there is no full and final statement of the theory. What follows is a presentation of "classical" psychoanalytic theory, which emerged from 1905 to 1920 and which is best represented by Freud's Five Lectures on Psychoanalysis (1910),Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis (1915-1916, 1916-1917), and the New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis (1933). While not intended in any way to be a historical account, we will have occasion to describe some of the ways in which the theory evolved in Freud's own mind. For other accounts, see Blum (xxxx), Hall (xxxx), Hall and Lindsay (xxxx), Monte (xxxx), and Sulloway (xxxx).

The Theory of the Instincts

Freud's fundamental assertion was that personality is rooted in a conflict between instinctual forces on the one hand, and environmental forces on the other. Essentially, Freud's view of personality is that of tension-reduction, based on a hydraulic model. Water in motion exerts pressure on its container, such as a dam or a valve, creating a flow that must be stopped or rechanneled. If it is stopped, it will continue to build up pressure, with damaging results (as when a dam bursts or a pipe breaks). If it is rechanneled, it may be given a controlled release -- thus averting disaster and , perhaps, making a potentially destructive force available for constructive purposes.

As with a waterworks, so it is with personality. Instincts strive for expression, in terms of both thought and action, but they conflict with environmental forces and must be controlled. The person mobilizes various psychological defenses to suppress and transform these instincts, which despite these efforts continue to seek direct or disguised expression. Personality (Freud used the term "character" in the broadest sense) consists of the person's habitual mode of adaptation to this conflict between internal and external forces.

To this basic model Freud adds a developmental theory. He asserted that the nature of the instinctual forces changed as the child matures from infancy to adolescence and adulthood. Also, he held that the individual's adaptation to the conflict is largely determined by events occurring during this time, particularly in early childhood. Without the instincts, however, there would be no personality to develop.

An instinct may be defined as a mental representation of somatic excitation -- that is, as a wish which expresses an innate bodily need. The instinct drives behavior intended to satisfy the physical motive, and thus to reduce the original need. This emphasis on tension- reduction marks behavior as conservative, seeking equilibrium, and regressive, seeking a return to a prior state. In this way an endless cycle of excitement and quiescence emerges, which Freud named the repetition compulsion.

Freud discerned four components to an instinct.

-

Its source is the bodily need which must be satisfied.

-

Its aim is to eliminate the source of the need.

-

Its impetus is the amount of force or energy associated with the instinct.

-

And its object is the behavioral or cognitive activity that will accomplish the aim.

The source and aim of an instinct are of course nearly identical, and the former remains constant throughout life. The internal aim, or final goal of an instinct, also remains constant. However, the external aim, the subgoals accomplished on the path to the final goal, can change. The impetus varies as the need is satisfied or frustrated. Finally, the object, like the external aim, can vary according to the individual's developmental stage as well as external constraints.

In his early writings on the subject, Freud (1910) offered a division between the life-maintenance and the sexual instincts. The former consist of biological needs necessary for individual self- preservation. The latter consist of needs, still biological in nature, that are necessary for preservation of the species as a whole rather than any particular member of it. For the individual, the sexual instincts are important only in that they give pleasure. Freud paid little or no attention to the life-maintenance instincts because he observed that they were rarely the source of conflict and anxiety. However, such difficulties did seem to surround the sexual instincts, and Freud gave a special name --libido -- to the energy associated with them.

Upon further reflection, however, Freud noticed that people appeared compelled to repeat unpleasurable as well as pleasurable experiences. For example, a common children's game involves making some favorite object disappear, and then reappear to view. Moreover, adults were often plagued by repetitive traumatic imagery, fantasies, and daydreams of the sort familiar to anyone who has ever been in a serious accident or been embarrassed in public. From these sorts of observations, Freud concluded that his earlier analysis of the instincts was incomplete. The life of the instincts is not, as first appeared, dominated by pleasure. Rather, the fundamental desire that underlies all the instincts is to return to some pre-existing state of quiescence and inactivity. Borrowing a term from Buddhism, Freud referred to this state as nirvana. According to Freud, the desires for pleasure and for quietude are separate and complimentary, but in the final analysis the latter is the fundamental instinct. But taken to the logical extreme, such a statement seems paradoxical. The ultimate state of quiescence for living things is death.

Later in his career, Freud (1924) proposed a new classification of the instincts.

-

Eros included the life and sexual instincts, those concerned with the continuity of life.

-

Thanatos are the death instincts.

The names for the instincts are the Greek words for love and death, respectively. According to this new scheme, eros serves thanatos by preserving the organism until it naturally dies. But eros also conflicts with thanatos, transforming the need for self-destruction into a need to destroy others. Freud held that the products of eros are love and sex, while the products of thanatos are hate and aggression.

Freud never fully developed his notion of a death instinct, though World War I convinced him that such a drive toward self-destruction existed. How else to explain how such a mindless orgy of violence and death could occur? While acknowledging the existence of thanatos, then, Freud focused most of his systematic thinking on eros, particularly in its sexual aspects. Our presentation of Freud's theory shares this emphasis. In discussing the sexual instincts, however, it is crucial to bear in mind that Freud defined sexuality very broadly, so that it went beyond intercourse and orgasm to include many different objects, all of which have their source in the desire for pleasure.

The Structure of the Mind

The instinct theory revolves around the fate of certain ideas, memories, and impulses to action. This makes Freud's theory of personality cognitive as well as biological. Accordingly, his theory has something to say about the structure of the cognitive system in which these processes take place. (Erdelyi [1986] has attempted to translate Freudian theory into the principles of cognitive psychology).

![]() Freud's earliest theory of

the mind, put forth in The Interpretation of Dreams

(1900), is called topographical because it maps the

mind into several compartments holding various types of

mental contents.

Freud's earliest theory of

the mind, put forth in The Interpretation of Dreams

(1900), is called topographical because it maps the

mind into several compartments holding various types of

mental contents.

-

The first of these, called the System Cs (for conscious ), contains those percepts, ideas, memories, impulses, and actions of which the person is presently aware.

-

Of course, Freud recognized that we are not simultaneously aware of everything that we know, or that is going on around us. We focus our attention on some things and either filter others out, fail to pick them up, or actively ignore them. Accordingly, he identified as System Pcs (for preconscious) which holds dormant contents that are not presently active and in consciousness. Preconscious contents are potentially accessible to the person.

-

Finally, he postulated a System Ucs (for unconscious), which contained those ideas, impulses, and the like that actively guide thought and action, but are inaccessible to consciousness.

Unfortunately, as Chomsky (1980) has noted, some confusion has been caused by Freud's inconsistent definitions of these terms. At times he asserted that material in the System Ucs was, in principle, inaccessible to conscious awareness and control. At other times he conceded that such material might be accessible under certain special conditions. However, the distinction between the System Pcs and System Ucs on the grounds of accessibility is clearly stated in The Interpretation of Dreams. There Freud describes the System Ucs as containing information which cannot be brought into phenomenal awareness and placed under voluntary control.

The movement of mental contents through the three systems follows lines of cathexis (attention) and anticathexis (avoidance or suppression). Mental contents can be transferred between Pcs and Cs at will: cathexis activates some content and brings it to mind. Cathecting something new deactivates the former contents of Cs and allows it to return to a dormant state. However, the erection of an anticathexis between Ucs and Pcs creates an effective barrier to consciousness, so that material held in Ucs cannot be brought to mind by an act of will.

Freud's topographical theory was almost his last gasp as a neurologist -- his very last was an unwillingly written revision of his books on cerebral palsy. It seems clear that in his earliest conception, the systems Ucs, Pcs, and Cs were construed as discrete locations in the brain where corresponding ideas were stored. Later, the topographical theory took the form of a flowchart, without much implication that the systems had separate physical representations in the biological structures of the mind. Finally, the terms conscious, preconscious, and unconscious dropped to the status of descriptive labels identifying a property of mental contents -- whether they were accessible to consciousness or not. This evolutionary trend laid the groundwork for Freud's final theory, announced in The Ego and the Id (1923). This theory is called functional because it classifies mental contents according to what they do, and the principles according to which they operate, rather than where they are.

The id (German for it) was identified by Freud as the seat of the instincts, and the reservoir of all the psychic energy, including libido, available to the person. (Notice how difficult it is to forswear spatial metaphors when talking about the mind, even when one has explicitly rejected a topographical theory in favor of a functional one.) Thus there is a constant amount of psychic energy behind both eros and thanatos, available at birth. The id is infantile and primitive. Its sole function is to gratify instinctual urges. Two modes are available for this direct expression. One is physiological, and amounts to an automatic discharge of the instinct through reflex action. A common example is sneezing in response to an irritant in the nose; another is urination and defecation in infants who have not yet been toilet trained, in response to waste material entering their bladders or rectums. The other is psychological, and is called the primary process. Here the person forms a mental image of the object of the instinct, resulting in hallucinatory wish-fulfillment. The id is amoral (not immoral), and operates according to the pleasure principle. By this, Freud meant that it seeks immediate gratification of the instincts, and is incapable of delaying, modifying, or otherwise controlling its urges. Primary process thinking is also entirely subjective, and illogical. It is not at all concerned with objective reality, and makes no distinctions between an external, physical object, and an internal, mental representation of it.

The nature of primary process thinking means that people cannot depend on the id alone to satisfy their needs. Hallucinatory wish- fulfillment may do for a while, in the absence of the real thing, but ultimately of course it is not enough. For this reason, a second set of mental processes must develop and come into play. These were named the ego by Freud. Its function is to take into account the demands and constraints of the external physical world. The emergence of the ego provides the first occasion for the development of object relationships, in which the individual finds objects that appropriately satisfy the instinctual drives. The ego is objective rather than subjective. It has the ability to distinguish external objects from internal representations of them. It operates according to the reality principle, postponing the discharge of an instinct until an appropriate object has been located. The invocation of the reality principle, then, involves the temporary suspension of the pleasure principle.. The characteristic function of the ego is the secondary process. By means of this function the ego discovers the nature of external reality by means of logical thought and action. It also employs reality testing, by which it puts a plan into effect in order to see whether it will achieve the aim of the instinct.

Freud held that the ego begins to differentiate from the id at about one year of age. The development of the ego largely depends on the attitude of the child's parents and other caretakers. Particularly important was the extent to which they offered a healthy balance of frustration and satisfaction. Such a mix is necessary for proper psychological development. Without some frustration, the ego never develops. Without some satisfaction, the child retreats to the id and is forced to rely on hallucinatory wish-fulfillment. In other words, both deprivation and overindulgence lead to a weak, unhealthy ego.

The ego develops so that the individual can live in a physical environment, but the social environment must also be considered. Of all the objects that are capable of satisfying instinctual needs, the culture deems some more appropriate than others. Therefore, at some point -- Freud thought it was about age 3 -- the child's parents and other authority figures begin to substitute moral choices for strictly realistic ones. As the social environment begins to guide acceptable object-choices, a third set of mental processes develops. These, known as the superego, take moral values into account.

The mechanism of superego development is the identification of the child with his or her parents, authority figures, and heroes -- a minister, priest, or rabbi; a nursery-school teacher or next-door neighbor; Wonder Woman or Captain America. Through identification the child acquires an internal, mental representation of rewards (the ego ideal) and punishments (conscience). In this way children acquire the ability to judge and guide their own thoughts and actions even in the absence of parents, authorities, and heroes. According to Freud, the superego -- like the ego -- acquires strength as it masters the instinctual urges arising from the id. This leads to the paradox that successful renunciation of instinctual desires makes the superego stronger -- and the conscience more, not less, severe.

Freud summarized this picture by saying that "the ego must serve three harsh masters": the instincts arising from the id; the demands of physical reality; and the strictures of society. The three functions -- id, ego, and superego -- are in perpetual conflict, and this conflict is the central, and inescapable, core of personality. The individual's solution to the problems posed by conflict is represented by his or her own idiosyncratic system of cathexes (object-choices) and anticathexes (barriers to object-choices). These choices, in turn, are motivated by three kinds of anxiety.

-

Reality anxiety stems from the dangers of the physical world.

-

Moral anxiety reflects the dangers of the conscience.

-

Neurotic anxiety is due to the dangers posed by the social world. The ego performs its mediating function by engaging in a variety of defensive maneuvers designed to deflect, suppress, and disguise instinctual demands.

The Mechanisms of Defense

All of the defense mechanisms are irrational in that their purpose is to deny, distort, or falsify reality -- the psychological reality of the instinctual urges arising from the id. They also operate unconsciously. After all, defenses are barriers to self-knowledge, and this purpose would not be served if the person were aware that he or she was engaging in them. Finally, they deplete the resources of psychic energy needed for other purposes, ultimately leading to a loss of flexibility and adaptability in thought and action. The paradox of the defenses, then, is why we have them at all. The answer, according to Freud, is that these defenses arise during childhood, when the newly developing ego was too weak to cope with all the demands that were made on it. They persist in adulthood, he said, because the defenses effectively prevent the ego from ever becoming strong enough to get along without them.

Before erecting defenses against internal, psychological forces, the individual's self-protective activities are directed against external, environmental ones. Withdrawal and avoidance remove the source of the threat of course, but the power imbalance that exists between the child and the world outside is such that escape attempts are doomed to failure. This leads to denial of external reality, but again this is ultimately impossible. In the face of an apparent inability to do anything about external forces, then, various means are devised to cope with the internal ones. Freud described a number of these cognitive coping techniques. His daughter Anna (of stwabewwies fame) presented a systematic analysis of them in her book,The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defense (1946).

The primary defense mechanism is repression, the brute-force suppression of instinctual impulses and those ideas, memories, and emotions that are associated with them. Repression reveals the primary characteristic of the defense mechanisms, which is their internal orientation. Rather than denying the threat from outside, people deny that in themselves which brings on the threat. Freud discussed three kinds of repression.Primal repression suppresses mental contents that have never been permitted to become conscious.Repression proper is a kind of cognitive afterexpulsion which operates on contents that have once been conscious.

In conversion, the anticathexis is so strong that it inhibits bodily functions associated with the repressed mental contents, as well as the thoughts themselves. In the last case, the organ systems are physiologically sound, but the information processed by them fails to reach consciousness; and the person has no conscious control over their operation. The result is a "hysterical" anesthesia or paralysis which is often symbolic of the repressed urges. Thus a loss of feeling in the lower trunk can represent repressed sexual urges, while a paralysis in the arm can represent repressed aggression.

The problem with repression, and it is a big one, is that it requires such an enormous expenditure of energy that there is little left over for other cognitive and behavioral activities. And because the repressive barrier is studded with weak points, unacceptable material can force its way through anyway. For these reasons, other, more elaborate maneuvers develop in order to support and supplant repression.

In projection, for example, the individual attributes his or her unacceptable feelings and wishes to someone else. In this way, people deny responsibility for unacceptable urges and their consequences. The outcome of projection, of course, is to transform moral and neurotic anxiety -- that is, the fear of societal strictures, or that one's instinctual impulses will run wild -- into reality anxiety -- of someone, or something,out there. Rather than forcibly suppressing the impulse, then, the person can actively express it in the guise of defending oneself against the impulses of others. In the Freudian view of things, projection explains why some people engage in "witchhunts" and other persecutions of anarchists, homosexuals, sexual deviants, violent revolutionaries, and others whose attitudes and behaviors are deemed antisocial. A special form of projection is scapegoating, in which a person attributes unacceptable impulses to members of some social outgroup like Blacks, Chicanos, or Jews (or, post-9/11, Muslims). In addition, there is shared projection in which the person attributes unacceptable impulses to everyone, including him- or herself. There are those who say that psychoanalytic theory, which began to develop as Freud concluded his self-analysis in The Interpretation of Dreams, was a massive exercise in shared projection.

Reaction formation occurs when the person transforms unacceptable impulses into their opposites -- love into hate, hate into love. In this way, the person hides his or her true wishes by displaying, and acknowledging, ones that do not cause anxiety. The giveaway is when the attitude or wish is displayed in an extravagant, persistent, and inflexible manner. When, in Hamlet Shakespeare has The Player Queen claim that she honored her husband, Gertrude (Hamlet's mother, who has conspired in the assassination of his father, her husband) replies "The lady doth protest too much, methinks". Similarly, friendliness can mask fear, machismo feminine tendencies in men, and altruism selfishness. A concern with chastity and romantic love may be a cover for lust and sexual depravity, and outward conformity can disguise inward rebelliousness -- and, of course, vice-versa.

Other defenses also may be noted.Rationalization consists in making reasonable, plausible excuses for one's conduct. These cogent reasons hide the instinctual origins of the thought or action. Common examples are striking someone in the course of teaching self-defense, and reading Playboy for the interviews.

Similarly, in intellectualization the person strips his or her primitive impulses of their emotional meaning, and turns them into intellectual or academic problems. A Freudian would have a field day explaining why some psychologists focus their research and teaching on violence, aggression, pornography, and sexual behavior.

Isolation also separates emotion from cognition, but by a process similar to the habituation of classical conditioning. The person fixates on the idea or impulse, rehearsing it over and over again, until the affect dissipates and only a cold idea remains.

Some defense mechanisms actually allow the instinctual impulse to be expressed -- although, of course, the actual origins of the act are repressed and remain unknown. Thus, in acting out the person gives into the impulse, engaging in all sorts of undesirable sexual and aggressive behavior. This is an interpretation often given to sexual promiscuity and juvenile delinquency.

Somewhat along the same lines,counterphobia is suspected when the person engages in excessive activity in some area of behavior that is the source of anxiety and defensive concern.

Finally, in undoing the person seeks to cancel out or compensate for the effects of thinking an unacceptable thought by engaging in some opposite activity -- protecting or nurturing one who is the object of aggressive impulses, for example. This defense lies at the room of many of the behaviors diagnosed as obsessive-compulsive. Neurotic individuals sometimes repetitively experience some anxiety-arousing thought or action tendency, and then engage in some behavior that is designed to remove or prevent the effects of the thought or action.

Sadly, all of these defenses are ultimately doomed to failure, precisely because they attempt to thwart instinctual demands which simply must be met. What the person requires, in order to adequately meet the demands of the three harsh masters, is some means for a more direct, though controlled, expression of instinctual impulses. While the defense mechanisms discussed so far attempt to change the source or aim of an instinct (something that is biologically mandates and thus cannot be altered), other more adaptive defenses operate on its object. Rather than denying the instincts, then, these defenses attempt to find a socially acceptable way of venting them.

One of these is displacement, in which a new object is substituted for the original. This new object choice is shaped by both social sanctions and the degree to which the substitute object resembles the original. Because according to Freud the child's first love is the parent of the opposite sex, for example, Freudian theory predicts that men will fall in love with women who are like their mothers, and women with men who are like their fathers. In this way, the social institution of marriage provides an acceptable, if disguised, way of expressing primitive motives. Displacement also occurs in clinical psychoanalysis, where the patient relates to the therapist as if he or she were the parent or some other significant person. This form of displacement is known as transference.

In creative elaboration, by contrast, the original goal object appears in disguise during daydreams, nightdreams, and other fantasies. These object choices are unconstrained by social strictures precisely because the objects are unrealistic and unattainable. The girl who imagines herself romantically involved with Mel Gibson, or the boy who dreams of being stranded on a desert island with Sigourney Weaver, poses no threat to society. Nor does the boy who puts himself in the boxing ring with Muhammad Ali, or the girl whose fantasies involve beating Joan Benoit to the finish of the Boston Marathon. (However, in the case of John Hinckley, Jr., whose infatuation with Jodie Foster was the motive for his 1981 attempt to assassinate President Reagan, such a threat can occur when fantasies are replaced by actions.)

Finally, in sublimation the person channels the mental energy lying behind an instinct into cultural activities such as painting, sculpture, musical composition, philanthropy, and public service.

Even these defense mechanisms are not completely satisfactory, however. Primitive instincts strive for direct, unbridled expression. Any attempt to transform them or deflect their energy prevents this from happening. The result is some degree of residual tension, as manifested in the "nervousness" characteristic of everyone (or so Freud thought), whether or not they are diagnosed neurotics seeing a psychotherapist. This tension is unavoidable, and in Civilization and Its DiscontentsFreud (1930) suggested that this is the price that we pay for living in a civilized world.

The defense mechanisms illustrate important features of psychoanalysis as a depth psychology. In each case, the behavior arises from a source which is kept hidden from oneself and others. Whatever one's immediate motives may be (or may seem to be), they are always derivative, somehow, of primitive sexual and aggressive instincts. Moreover, the operation of the defenses means that any activity is overdetermined. That is, any action can satisfy one of many instinctual demands. Kissing can be sexually gratifying, or it can represent the displacement of instinctual sucking, thus gratifying hunger and thirst; kissing too hard can be an act of aggression. For farmers and gardeners, tilling the soil and reaping the harvest may satisfy one's sexual instincts, while planting seed and tending crops may satisfy sexual urges. Interpersonal aggression may stem from acting out, or perhaps counterphobia; alternatively, it may be a reaction-formation against love, or a projection of the death instinct. The instinctual source, and the mechanism by which the unconscious instinct is transformed into manifest thought and action, cannot be determined in advance according to a kind of "symbol book" such as those found in supermarket checkout lines for the interpretation of dreams. Rather, they must be uncovered in each individual case by means of free- association.

Two other defense mechanisms, regression and fixation, remain to be discussed. However, they take on meaning only in the context of Freud's theory of personality development, to which we now turn.

Defense and Transformation

Suppes and Warren (1975) have proposed a mathematical model of the kinds of transformations involved in the Freudian defense mechanisms. They begin with a propositional representation of unconscious affect -- of an actor, an action, and an object (x) of the action -- as in the prototypical Freudian emotional self-disclosure:

I (actor)love (action)my mother (object x).

They then go on to show that some 44 different defense mechanisms, including all those included in the standard list, can be produced by just eight transformations applied to the actor, the action, or the object, alone or in combination -- e.g., the transformation of self to other, of an action into its opposite, or from object x to object y. Thus,

-

Displacement retains the original actor and action, but changes the object from x to y: I love my father.

-

In reaction formation, the actor and object remain constant, but the action is changed into its opposite:I hate my mother.

-

In projection, the action and the object remain constant, but the actor is changed: Saddam Hussein loves my mother.

Applying all three transformations, we obtain Saddam Hussein hates my father -- a glib and vulgar Freudianism, to be sure, but one which nicely illustrates the essential process by which the defense mechanisms are held to operate so as to render the actual emotional and motivational determinants of our behavior inaccessible to phenomenal awareness.

Infantile Sexuality

In discussing the defense mechanisms we often had occasion to use examples with some sort of sexual content. This choice was not dictated by a desire for dramatic effect, or for salaciousness, but because -- as indicated earlier -- Freud felt that sexual motives were at the center of personality. Along with the aggressive urges of thanatos, these are the instincts which arise from the id, and which must be controlled by the ego and superego. These are the urges that the defense mechanisms are deployed to control. Now, nobody would argue that sexual issues are unimportant to personality. Once a person reaches puberty sex becomes a very real issue indeed, and many of the problems confronting adolescents and adults are sexual in nature. But Freud went further than this by claiming that sex is the issue,from birth. Sexual impulses are present in neonates, and continue to seek expression and gratification until death. This notion ofinfantile sexuality is Freud's most radical hypothesis. While the concept of unnconscious mental processes was quite familiar from the work of the First Dynamic Psychiatry, infantile sexuality was totally new -- and, to polite society in Victorian Europe, totally outrageous.

At the start, Freud simply made the observation -- as in "The Dream of Irma" and "The Aliquis Episode", both recounted above -- that many neurotics were troubled by difficulties in the sexual sphere. This is not surprising, given the societal restrictions imposed by Victorian society on the upper classes into which Freud was born and from which he drew his clientele. Quite soon, however, Freud became impressed with the frequency with which his hysterical, phobic, and obsessional patients reported incidents of overt sexual seduction during childhood. That is, during free association many patients stumbled on a forgotten experience in which some sexual act had been performed by, or with, a parent or some other adult authority figure. The following case, reported by Freud (1894) in The Neuro-Psychoses of Defence (p. 55), is typical.

A girl suffered from obsessional self-reproaches. If she read something in the papers about coiners, the thought would occur to her that she, too, had made counterfeit money; if a murder had been committed by an unknown person, she would ask herself anxiously whether it was not she who had done the deed. At the same time she was perfectly conscious of the absurdity of these obsessional reproaches. For a time, this sense of guilt gained such an ascendancy over her that her powers of criticism were stifled and she accused herself to her relatives and her doctor of having really committed all these crimes.... Close questioning then revealed the source from which her sense of guilt arose. Stimulated by a chance voluptuous sensation, she had allowed herself to be led astray by a woman friend into masturbating, and had practised it for years, fully conscious of her wrong-doing and to the accompaniment of the most violent, but, as usual, ineffective self-reproaches. An excessive indulgence after going to a ball had produced the intensification that led to the psychosis. After a few months of treatment and the strictest surveillance, the girl recovered.

From reports such as these, Freud abstracted the following hypothetical sequence of events. The child has some sexual experience, but by virtue of his or her immaturity is incapable of arousal and pleasure, and psychologically unable to understand what has happened. For these reasons, the experience is forgotten -- not in the sense of being lost to memory entirely, but rather in the sense of being too weak to be memorable. In adolescence and adulthood, however, new sexual experiences revive the memory of the childhood ones, evoking anxiety and guilt. These negative emotions lead first to repression and other defenses, and ultimately to the formation of neurotic symptoms. These forgotten childhood experiences must be retrieved by free association, and relived with full emotion, before the neurotic symptoms will abate.

Almost as soon as it was advanced, Freud began to have problems with the theory of infantile seduction. In the first place, he had to contend with the reason that the sexual episode was forgotten. People often remember events from their childhoods, be they trivial or earthshaking. Moreover, the theory led to the inescapable conclusion that incest and other sexual forms of child abuse were near universal -- a conclusion vehemently denied by the parents and physicians of Freud's day, and rather incredible in any event. Finally, Freud recognized that the Ucs was incapable of separating fantasy from reality. Considerations such as these led Freud to revise his theory to assert that these seductions took place in the child's fantasies rather than in real life. This, in turn was taken as indicative of the sexual interest of even very young children. Therefore, Freud held, seduction is a universal fantasy even if it is not a universal fact.

The rest of the sequence had to modified as well. The imaginary expression of these sexual urges in the child arouses anxiety, and inspires the various defensive maneuvers. The truth of these assertions was apparently confirmed by Freud's self-analysis, as contained in The Interpretation of Dreams, in which he uncovered his sexual feelings toward his own mother.

At this point, it seems appropriate to remind the reader that for Freud, sexuality is not confined to masturbation, intercourse, and other genital activities. Rather, sexual activity includes anything that leads to pleasure. Freud's portrait of the infant, however immature, as an active seeker of pleasure was his most radical insight. It led him to a theory of psychological growth that traced the various forms that this pleasure-seeking can take.

Stages of Psychosexual Development

For Freud, all instincts have their origins in some somatic irritation -- almost literally, some itch that must be scratched. In contrast to hunger, thirst, and fatigue, however, Freud thought that the arousal and gratification of the sexual instincts could focus on different portions of the body at different times. More specifically, he argued that the locus of the sexual instincts changed systematically throughout childhood, and stabilized in adolescence. This systematic change in the locus of the sexual instincts comprised the various stages of psychosexual development. According to this view, the child's progress through these stages was decisive for the development of personality.

Properly speaking, the first stage of development is birth, the transition from fetus to neonate. Freud himself did not focus on this aspect of development, but we may fill in the picture by discussing the ideas of one of his colleagues, Otto Rank (1884-1939).

Rank believed that birth trauma was the most important psychological development in the life history of the individual. He argued that the fetus, in utero, gets primary pleasure -- immediate gratification of its needs. Immediately upon leaving the womb, however, the newborn experiences tension for the first time. There is, first, the overstimulation of the environment. More important, there are the small deprivations that accompany waiting to be fed. In Rank's view, birth trauma created a reservoir of anxiety that was released throughout life. All later gratifications recapitulated those received during the nine months of gestation. By the same token, all later deprivations recapitulated the birth trauma.

Freud disagreed with the specifics of Rank's views, but he agreed that birth was important. At birth, the individual is thrust, unprotected, into a new world. Later psychological development was a function of the new demands placed on the infant and child by that world.

From birth until about one year of age, the child is in the oral stage of psychosexual development. The newborn child starts out as all id, and no ego. He or she experiences only pleasure and pain. With feeding, the infant must begin to respond to the demands of the external world -- what it provides, and the schedule on which it does so. Initially, Freud thought, instinct-gratification was centered on the mouth: the child's chief activity is sucking on breast or bottle. This activity has obvious nutritive value: it is the way the child copes with hunger and thirst. But, Freud held, it also has sexual value because the child takes pleasure in sucking; and it has destructive value because the child can express aggression by biting.

Freud pointed out that the very young child needs his or her mother (or some reasonable substitute) for gratification. Her absence leads to frustration of instinctual needs, and the development of anxiety. Accordingly, the legacy of the oral stage is separation anxiety and feelings of dependency.

After the first year, Freud held, the child moves into the anal stage of development. The central event of the anal stage is toilet training. Here the child has his or her first experience with the external regulation of impulses: the environment teaches him or her to delay urination or defecation until an appropriate time and place. Thus, the child must postpone the pleasure that comes from relieving tension in the bladder and rectum. Freud believed that the child in the anal stage acquired power by virtue of giving and retaining. Through this stage of development, the child also acquired a sense of loss, and also a sense of self-control.

The years from three to five, in Freud's view, were taken up with the phallic stage. In this case, there is a preoccupation with sexual pleasure derived from the genital areas. It is at about this time that the child begins to develop sexual curiosity, exhibits its genitalia to others, and begins to masturbate. There is also an intensification of interest in the parent of the opposite sex. The phallic stage revolves around the resolution of the Oedipus Complex, named for the ancient Egyptian king who killed his father and married his mother, and brought disaster to his country. In the Oedipus complex, there is a sexual cathexis toward the parent of the opposite sex, and an aggressive cathexis toward the parent of the same sex.

The beginnings of the Oedipus Complex are the same for boys and girls. Both initially love the mother, simply because she is the child's primary caretaker -- the one most frequently responsible for taking care of the child's needs. In the same way, both initially hate the father, because he competes with the child for the mother's attention and love. Thereafter, however, the progress and resolution of the Oedipus complex takes a different form in the two sexes.