by Olivia Hemond

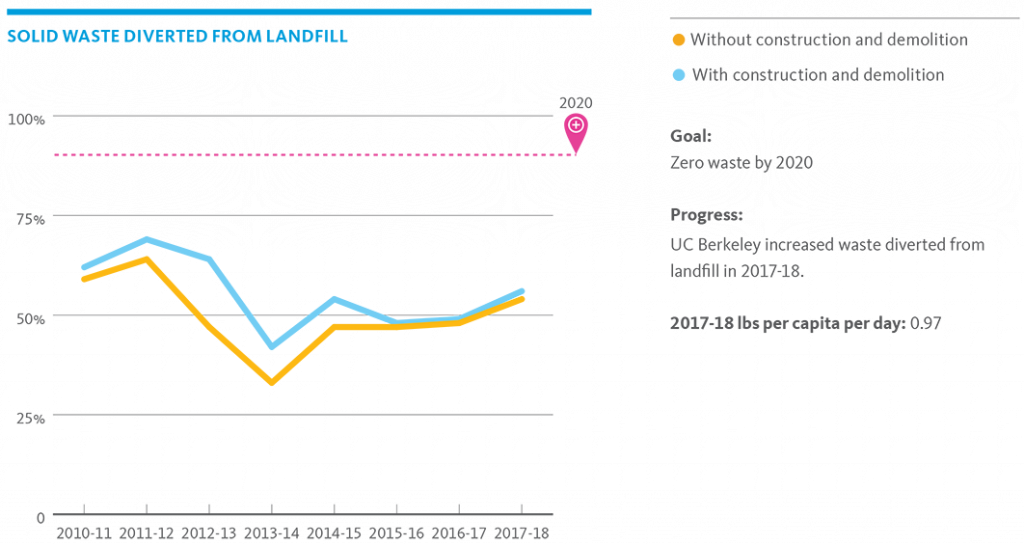

UC Berkeley community members may have noticed the signs around campus advertising the goal of “Zero Waste by 2020.” The campaign has reduced the amount of waste the campus sends to landfills by 20% since 2012, although the pandemic has temporarily disrupted recent operations. Now, moving forward from its titular year, the Zero Waste by 2020 and Beyond initiative is working to improve its waste practices and incorporate inclusive and justice-oriented narratives.

With over half a million people involved in the UC system, improvements from each campus have the potential to accumulate and create significant impacts. Since 2004, the UC system has created goals through the initiative, setting targets to divert 90% of solid waste away from landfills, reduce waste generation to less than half of 2015-2016 levels, and eliminate single-use plastics and styrofoam packaging products.

Due to the variation in operations across the UC system, each campus is responsible for creating its own strategic plan to meet these zero waste goals. UC Berkeley has started by reducing its per capita waste generation and increasing the rates of waste diversion from landfills. According to the 2019 UC Berkeley Zero Waste Plan, these efforts have decreased the amount of waste sent to landfills from 4,600 tons of landfill waste in 2012 to under 4,000 tons in 2018. Students have played a large role in creating and updating the plan by forming partnerships across campus organizations, as well as creating a Zero Waste DeCal course to educate their peers on systemic environmental solutions.

“It’s been incredibly encouraging to see all of the support across personnel,” said Jessica Heiges, a UC Berkeley Ph.D. candidate studying waste management. “That’s rare, to have such a multidisciplinary coalition formed around a single vision.”

In April 2020, UC Berkeley also committed to the strongest plastic ban in the country. This policy aims to eliminate all nonessential single-use plastic products on campus by 2030 by identifying and phasing out these products within food service, academics, research, administration, and campus events.

“[The policy] is making sure we get there now, and it’s not just words,” said Madi Alcalay, a co-facilitator of the Cal Zero Waste Lab.

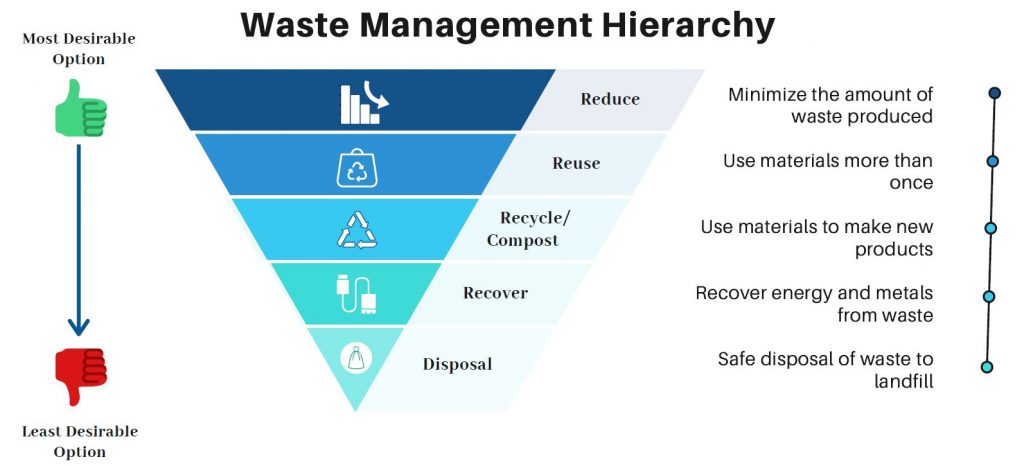

To facilitate change across the campus, the UC Berkeley Zero Waste Plan targets waste at multiple points. It incorporates “upstream” waste management practices, which focuses on minimizing the amount of waste produced. This can mean promoting the use of reusable water bottles and coffee mugs through the Refreshing Refills campaign or working with campus eateries to adopt specific zero waste practices.

The plan also includes “downstream” strategies, which deals with materials once they’ve entered the waste stream. The goal of these strategies is to minimize the amount of waste that ends up in landfills through the reuse of products and proper waste sorting.

Julia Sherman, Chair of the Zero Waste Coalition at Berkeley, believes that the standardized signage and Big Belly Solar Compactor bins on campus have helped the community learn how to sort their waste, as have educational campaigns during student orientation and within the dining halls. As many waste processing facilities do not sort waste onsite, proper waste sorting plays a critical role in diverting waste from landfill.

“It’s been a work in progress through standardizing signage, standardizing infrastructure, and education,” said Sherman. “I think we’re slowly getting there in terms of students understanding where things go.”

Despite these efforts, much work remains to reach the Zero Waste campaign’s targets; the campus’ diversion rate currently stands around 54%, which is much lower than the 90% goal. To help close this gap, Heiges proposes composting as a potential area where improvements in sorting can have beneficial downstream impacts.

“There’s so much opportunity for a higher diversion rate,” said Heiges. “If they end up in the landfill, organic waste generates methane, which is a very potent greenhouse gas. However, if the waste ends up in the compost bin and is then processed to create compost or soil, then it goes back into our environment and ultimately captures carbon.”

While Heiges highlights the advantages of effective waste sorting, she also points out that there are flaws within waste systems themselves. A recent NPR article found that despite plastic producers knowing that recycling is not a physically or economically viable solution, companies still market recycling as a solution to ease consumers’ concerns about using plastic. Less than 10% of all plastic ever produced has been recycled. Plastic loses quality each time it’s recycled, so it can only be recycled a few times at most before becoming landfill waste.

While composting is a potential solution for organic waste, some have raised issues with the process. For one, the presence of compostable bioplastics is growing in the form of compostable utensils, takeout containers, and cups. These items are made from plant-based materials and are often marketed as being more environmentally-friendly while maintaining the convenience of single-use disposable products. Their appeal seems to be sticking: according to European Bioplastics, these bioplastics comprise about 1% of all plastic produced today, and production is set to increase.

However, many composting sites do not have the capacity to actually compost these bioplastics. For example, the West Contra Costa Landfill, where UC Berkeley sends its compost, sorts bioplastics out of their waste stream and sends them to landfill.

Most bioplastic products require 90 days in a facility to break down completely, but the Contra Costa facility uses a 30-day turnover rate to handle the large volume of compost they receive. Additionally, the facility mainly produces compost for agricultural applications, but bioplastics are not nutrient-rich nor beneficial for soil.

“[Switching all our single-use plastics to bioplastics is more of] a band-aid solution,” Sherman said. “This doesn’t really have the ability to scale up because of the infrastructure we currently have.”

While we often associate waste with what we see in the garbage can, the entire waste life cycle poses an issue. By the time a product gets to the consumer in the form of a takeout cup or container, a significant environmental footprint has already been created.

“About seven to eight times the amount of waste is generated during the production process than what you put in your bin at home,” said Heiges. “That is what they call industrial waste or manufacturing waste, and it’s astronomically high.”

As downstream approaches alone cannot effectively minimize waste, some solutions turn to producing less waste in the first place. Reusing items and buying fewer products in the first place are two ways to reduce manufacturing waste. According to Varsha Madapoosi, a Cal Zero Waste Staff Associate and member of the Students of Color Environmental Collective, these practices are not new: Indigenous peoples and communities of color have been reducing waste and reusing items for generations, as these practices are built into many cultures.

Currently, the Cal Zero Waste Plan contains no mention of environmental justice. However, addressing issues of waste will require more investigation into the ways that they intersect with environmental justice issues.

“It’s the creation of the product itself. Where is it being created, who is working at those manufacturing facilities or those refineries, who is being exposed to those harmful production processes or those harmful production chemicals?” questioned Heiges. “What demographic is predominantly exposed to the chemicals that are inherently in these disposable goods? And then, finally, who is overseeing the collection and processing of the waste itself? All along these processes it’s minorities, it’s immigrants, it’s BIPOC, it’s disadvantaged communities that are being disproportionately affected by the consumption and disposal of waste.”

Once out of sight, it is easy to forget about the impact campus waste has on people outside the Berkeley community.

“When you throw something away, it never goes ‘away,’” Madapoosi said. “We send our recycling to a materials and cardboard facility in Richmond … that in itself is a form of injustice in that we’re sending our waste to a city that’s predominantly people of color and of lower socioeconomic status.”

Some students believe that recognizing the humanitarian issues behind waste management is key to creating successful community engagement with the zero waste goals. Sherman hopes to see more environmental justice education in the plan, as humanizing the waste system could help people better understand waste management practices and what they can do to help.

While waste sorting is a critical component to reducing waste overall, the responsibility should not solely lie on consumers. Heiges points out that individual consumer action alone cannot create the change necessary to decrease the amount of waste humans produce.

“How can we shift [the burden] from individuals as consumers to individuals as professionals?” asked Heiges. “How can we stop focusing on what we’re purchasing and start focusing on how we are contributing to society in our decision-making abilities in our careers? How can we, in our day-to-day jobs, make an impact versus how we as consumers make an impact? Because it’s just increasingly clear that there’s only so much we can do as consumers.”

Heiges hopes that this narrative can resonate with a broader audience, empowering more people to take action. While isolated individual consumer actions may not be enough to address the waste crisis, individuals working together as a diverse collective can be a powerful force for change.

“When people think ‘corporations are making all the plastic, we can’t do anything about it,’ there’s not as much individual action. But there can be a lot of change made with individual action,” said Alcalay.

When looking beyond 2020, Heiges is optimistic that waste management is headed in the right direction.

“I think waste is such an enormous problem that it’s very easy to feel overwhelmed by it,” said Heiges. “I urge and challenge everyone to take [the problems] instead as frames of possibilities and figure out what they can do as consumers, professionals, or members of civil society.”

Olivia Hemond (she/her) is a fourth year studying Molecular Environmental Biology with a concentration in Environment and Human Health. She loves that Perennial gives her the opportunity to investigate complex and interdisciplinary environmental issues. Through writing about these topics, she wants to help bridge the communication gap that often exists between environmentalists and members of the public. In her free time, she loves to hike, do pottery, and scuba dive.

Featured image: Global Anti Incineration Alliance Philippines Executive Director Froilan Grate standing in front of piles of plastic in Malaysia (Yulia Nesterova, Impakter)