Dr. Andrew Reddie is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California, Berkeley. His research examines the intersection of technology, international security, and experimental methods. He currently serves as a researcher for the Nuclear Policy Working Group and the Complexity Science and Nuclear Security Group in the Nuclear Engineering Department at UC Berkeley. His work has been published in Science, the Journal of Cyber Policy, Business and Politics, Nonproliferation Review, and Applied Network Science, and his commentary can be found in Canada’s Globe and Mail, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, Global Asia, and DefenseOne. Dr. Reddie and I sat down to have an engaging conversation about the future of cyber warfare, nuclear strategy, and the impact of new technology on international security.

Alex: More states today are acquiring advanced cyber capabilities, and costs associated with cyber attacks are rising. What factors explain this increase, and what can we do to lower the costs of cyber-attacks in the future?

Andrew: There are numerous factors driving the increased use of cyber attacks, such as ransomware, DOS/DDOS attacks, and viruses. While most of my work deals with state actors, the use of ransomware overwhelmingly tends to be non-state actor-led. Some states, with North Korea being the most obvious example, use ransomware as a method to raise money to fund government activities limited by the current sanctions regime. Ransomware works when those affected pay to get access back. WannaCry is a recent example of this phenomenon. Groups will try to lock people out of their systems and demand payment for re-entry, and it is an increasingly lucrative market for cyber-criminals.

Some of the most sophisticated cyberattacks, Stuxnet is often held up as an example, use advanced cyber capabilities, but the vast majority of cybercrime target low-hanging fruit and are not nearly as sophisticated. The costs associated with cybercrime arerising largely due to these comparatively “low tech” forms of attacks, like phishing. Companies have tried to educate their workforce on the dangers of these types of attacks. There is still an ongoing debate among experts as to whether the complexity of cyberattacks is increasing, as opposed to simply the volume of cyberattacks.

Alex: Let’s turn to the state level. The U.S. and China are now engaged in multiple layers of competition: militarily, economically, and in cyberspace. What explains China’s rise in the cybersecurity sector, and what can we do to match those capabilities?

Andrew: The competition between the U.S. and China is indicative of strategic competition–as multiple U.S. government policy documents point out. One of the most interesting things, as an academic, is that this competition is not taking place in a “Cold-War” manner in which there are armed proxy conflicts around the world. That is not where the entire competition is taking place. Instead, the competition occurs in which has increasingly been described as the “gray zone” short of war–including cyberspace.

China is increasing its nuclear arms, certainly, but there is competition in the digital space as well—5G, the Internet of Things, and quantum computing all offer technology sectors in which Beijing and Washington compete. China’s rise in those sectors is driven by its use of industrial policy tools to grow that market. The Chinese government decided that this was a strategic area that it wants to lead in, and have invested with these goals in mind. Chinese firms in 5G, such as Huawei and ZTE, are ahead of U.S. and European firms, largely because they have more government support.

One of the things that we are concerned about in the United Statesis the issue of technology transfer–in terms of both goods and human capital. There are also Chinese venture capital companies that get involved in U.S. startups. But one of the most common ways of technology transfers is by not allowing foreign competitors into your market without forming joint ventures. For access to the Chinese market, global firms are often required to partner with Chinese firms, which means that sharing occurs between them. Foreign firms face tradeoffs to work in the Chinese market. Do you want access to one billion Chinese customers at the cost of giving up some of your intellectual property? Some companies are saying yes, but this is still a tough call.

Alex: Staying on the state-level track, I wanted to ask you about a new development related to cyber security. Recently, more authoritarian states, such as China and Iran, have shut down the internet in response to protests. Will the use of this tool increase in the future to stifle dissent?

Andrew: That’s a good question. We saw this start during the Arab Spring in 2011, when organizers used social media to organize large-scale protests. One of the simplest ways to stop that organizing is to shut down the internet. However, as the Iran case makes clear, there are all sorts of secondary consequences to doing that, not least for your economy. The internet is relied upon to carry out work in the financial system and in trade. All of that relies on the internet. Governments need to weigh the costs of deploying this tool, including economic costs and impact on human rights. A lot of countries also deny that they are responsible for shutting down the internet and blame other actors when networks go down. The plausible deniability is an important feature of this type of decision taken by a government.

On the protest side, groups can be fairly creative. Protesters in Iran used Bluetooth devices to avoid the internet shutdown. Even during the Hong Kong protest, which is occurring as we speak, it’s evident that this tool does not always stop protests.

Alex: I want to pivot now to some of your work on nuclear weapons and nuclear weapons strategy. A big change occurred this year: the United States completed its withdrawal of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF). As you describe in your article in “Next Generation Nuclear Network,” the treaty (negotiated between the US and the USSR, now Russia) successfully eliminated 2,692 missiles, banned intermediate range nuclear weapons, and provided an on-site inspection mechanism. Why did the Trump administration leave the INF, and what does it hope to gain from doing so?

Andrew: For the first part, the United States withdrew from the INF as a result of a decade of Russian non-compliance. In 2014, the U.S. State Department announced that Russians had been non-compliant with the treaty since 2007 and the Russian weapons system that the U.S. believes is not compliant, a Russian ground-based launcher (9M729), can launch missiles over intermediate-range distances. The INF Treaty is also an awkward treaty. The INF bans missiles over a specific intermediate range (1,000 to 5,500km), and below that range is fine and above that range is fine. Inspections were carried out to enforce the treaty while Washington and Moscow eliminated their intermediate-range forces. I think that the best argument for withdrawal was that the US did not want to be part of a treaty regime in which the other party did not abide by the rules of the treaty. The argument on the other side is that the treaty architecture gave the United States a framework to re-engage Moscow and return to compliance down the road.

Some of the problems are embedded within the treaty itself. The verification regime actually ran out in 2001. Since then, we really haven’t had any serious negotiations within the INF treaty process. Some have gone so far to suggest that the Russians did not believe that it would be costly to build INF systems because they believed that the United States was not interested in enforcing the treaty. If you want a new INF, we probably require a new treaty framework that would establish a new verification regime.

In the months since leaving the treaty, the United States tested intermediate systems in September 2019, and it begs the question, in which theater would these systems be useful? Somes, like David Sanger, argue that these systems could be useful in the East Asian context. And of course, the INF treaty said nothing about the East Asian theater, as it is focused on the European theater involving the United States and Russia.

Alex: And speaking of the East Asian theater, China has never been a party to a negotiated treaty limiting its nuclear forces. What is the likelihood that China will do so, or is it unlikely that China will join a treaty regime?

Andrew: The multilateralization of arms control as a bit of a political football. Some commentators will say that we need to broaden something like New START to different states like China, and it is unclear whether they actually want to involve China or not. There is a broad consensus that extending New START to 2026 is a good thing to stabilize nuclear forces. It is important to remember what arms control is for. Arms control is not necessarily about disarmament, it is about pursuing strategic interests for the signatories. China will sign an arms control treaty when it is in its strategic interest to do so, and it really depends what the offer on the table is.

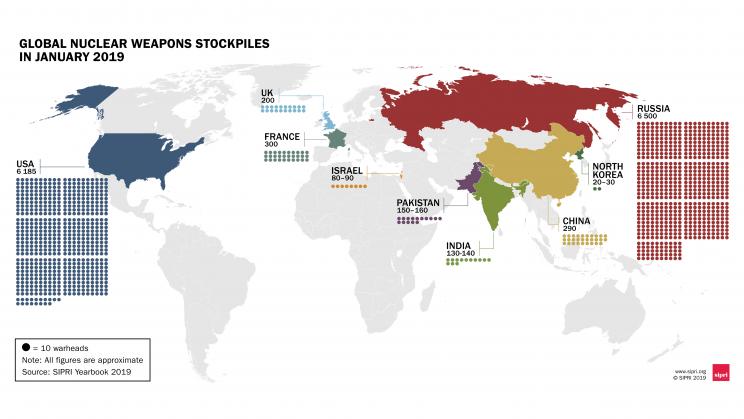

We have not seen a spike in the number of Chinese nuclear forces, but they have been moving to SLBMs (submarine-launched ballistic missiles). If the offer for China’s participation is similar to New START, limiting the number of warheads to 1,300, then there is no reason China would not sign up to that because the gap between America and China is so large with America having several times the number of warheads as China.

We are not talking about two symmetrical capabilities here. But as we move towards strategic parity between China and the United States, there is a good argument for socializing Chinese officials towards arms control–particularly as there is a stability benefit to being involved in these kinds of regimes.

Source: SIPRI

Alex: I want to move now to our last topic of discussion, wargames. You have done a lot of extensive work in this field. Wargame simulations are critical for decision-makers in our military and government to evaluate strategic decisions. Can you outline some of the recent challenges with contemporary wargames, and what future improvements can be made?

Andrew: In policy planning and training, we have relied on wargames for a long time. In the United States, the Naval War College deserves the most credit for building wargames as a training tool and RAND for using wargames as a method for inquiry. In the past we usually would bring in experts and ask them to go through a scenario. With wargames, we are strengthening the participants’ reflexes to policy planning under stressful conditions. If you are worried about a possible crisis, like confrontation in the South China Sea, wargames can sharpen officials’ responses in preparation.

One of the things you cannot do with these one-off wargames is that you cannot predict the likelihood of a crisis or event occurring “in the real world.” I can tell you how one situation takes place with the game rules and information that I provide, but we cannot predict the likelihood of conflict.

But now with the help of tools developed in fields of psychology, data science, and computer science, we can build wargames that appear more real and can be built with replicability in mind. The players must live with the consequences of their decisions in a way that they would not experience with other types of experiments. We are trying to make a richer experimental environment to make choices that we care about. These move away from traditional international relations’ research that focus mostly on states towards a behavioral lens that examines how human beings respond to strategic questions. What is a person’s first instinct, rather than asking what Washington wants? There is a need to incorporate more human behavioral aspects in wargames. We are more interested in finding those conflict escalation patterns. Thankfully we have the technology to deploy these wargames with computer systems at relatively low cost.

Alex: My last question is about new military technology. The hypersonic missile, which has attracted widespread attention, can travel at many times the speed of sound, while artificial intelligence could reshape the battlefield. What are the strategic implications of these systems, and will they be a source of stability or instability in the future?

Andrew: Some hypersonic weapons have a glide system where you can maneuver the warhead to a target, as opposed to following a predictable ballistic trajectory, evading anti-ballistic missile systems. The other type of hypersonic weapon, a scramjet system, can fly at a very low altitude with the goal of avoiding detection, and it is also maneuverable. These missiles are effectively built to overcome missile defense systems. In the low-altitude scramjet case, our missile defense cannot bring down these weapons at all. The telescopic targeting system won’t work to capture the trajectory of a low-flying missile.

Source: U.S. Air Force

Our current missile defense doctrine targets a one or two-missile launch scenario from Iran or North Korea, as opposed to a huge barrage from established nuclear powers like China or Russia. Our missile defense system could not deal with a barrage attack–and it is not designed to. And if you are a believer in nuclear deterrence, you actually don’t want any state to have a strong missile defense system. If you have a strong missile defense system, it might actually make you more likely to launch a preemptive strike because you believe that you can block the retaliatory strike against you. Missile defense actually undermines this stability.

With regards to AI and the future of warfare, there is a lot of fanfare around artificial intelligence. It is important to unpack what AI actually is and what it can add to warfighter capabilities. The AI technologies that are actually deployed in the field are pattern recognition and anomaly detection tools–and these tools aren’t new. Why are these useful? For example, if you want to look at an area of Iraq or Afghanistan, you can ask what events are occurring in a specific geography and then calculate the likelihood of events of interest based on historical data. This allows operators to deploy resources where they are most likely to have an impact. We are also getting better at layering image intelligence, signals intelligence, and human intelligence, and now we can have one operator analyze more information. However, there are costs to layering, such as determining the weight of each type of intelligence and which intelligence is driving a particular finding that AI systems, by themselves, are unable to address.

The basic takeaway is that AI is not as new as people make it out to be–we have been using a form of machine learning since the 1960s to identify patterns and threats.

These new technologies do not offer a panacea ; there will still be all sorts of evolving security challenges in the future for students, analysts, and officials to address.

Alex: Dr. Reddie, thank you so much for your time, I really appreciate it.

Andrew: My pleasure.