If you Google “Mali 2012 Timbuktu,” eight out of then of the first results speak of the cultural destruction and the loss of many protected sites in the city due to the insurgency of Ansar Dine. As the Google search shows, in 2012, the Tuareg Islamist terrorist group allegedly destroyed many cultural sites to denounce Timbuktu’s moderate Sufi Islam. In the 15th and 16th centuries, Timbuktu was the cultural center of West Africa. Its ancient manuscripts and other cultural objects were placed in the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1988 for having Outstanding Universal Value. After the destruction took place, mosques and other ancient treasures were restored and the International Criminal Court (ICC) tried Al Mahdi, the main perpetrator, for the destruction he inflicted in Timbuktu. However, this situation raises important issues. Namely, how you frame a conflict matters. Timbuktu suffers from extreme poverty, which renders people unable to pay for the upkeep of the manuscripts and mosques. People perceive attention to the cultural heritage is more important than people’s economic marginality and the damages they suffered during the 2012 crisis. The international community gives importance and attention to the destruction of heritage sites while ignoring the Malian people’s basic needs: this crisis conflicts with their human rights and dignity. Thus, while analyzing relevance, human rights like security should be prioritized over cultural rights in both the framing of conflicts and the structure of the response.

Comparative Importance of Timbuktu: A Regional Question

The case of Timbuktu’s manuscripts has been widely accepted as an example of the importance of cultural rights in the developing world. Clarifying the actual chain of events that took place in Timbuktu in 2012 is key to understanding the interplay between local and international dynamics regarding cultural rights. There is no doubt of the cultural and historical importance of Timbuktu as a cultural center. However, if we focus on West Africa as a region, we can appreciate that there are other places where Arabic manuscripts are of great importance – arguably greater than in Mali. In Mauritania, there are manuscripts in Oualata and in Chinguetti; and in Niger, there are many in Agadez. The cultural hub in West Africa containing the most valuable manuscripts is Mauritania, not Timbuktu, and yet the Malian region has received much more international funding and aid to preserve its cultural heritage, as denoted by UNESCO, although UNESCO’s World Heritage List includes Banc d’Arguin National Park and the ancient Ksour of Ouadane, Chinguetti, Tichitt and Oualata. This is, again, not to say that Mali’s cultural heritage doesn’t deserve attention: the analysis of manuscripts helps combat racism and offers a valuable insight into Malian culture. However, let’s ask another relevant question: why Mali and not others?

Source: African World Heritage

The importance of Timbuktu’s manuscripts has been successfully institutionalized through the language of “world heritage” that cultural elites have learnt how to use. For example, the Gerda Henkel Stiftung and the University of Cape Town funded a research project for Arabic manuscripts in Timbuktu. The international discourse surrounding the manuscripts is not rooted in deep historical analysis of their importance for Malians, but in the importance of world heritage and cultural rights in general as captured by the elites who benefit from privately funding and restoring such manuscripts.

Crisis in Mali: An account

In 2012, a Tuareg islamist terrorist group called Ansar Dine started a quarrel with Malian separatist fighters and took control of Timbuktu. Ansar Dine damaged many cultural sites such as mosques and mausoleums of Sufi saints to denounce the city’s moderate Sufi Islam. The armed uprising caused international outrage and Timbuktu’s historical sites were classified as endangered by UNESCO, whose director general Irina Bokova called the groups to protect the city’s heritage: “Timbuktu’s outstanding earthen architectural wonders that are the great mosques of Djingareyber, Sankore and Sidi Yahia, must be safeguarded,” she said. These actions were a war crime under the Rome Statute – the international law establishing the ICC. On 27 September 2016, leader Al Mahdi was convicted of intentionally directing attacks against religious and historical buildings in Timbuktu. It was the first time that an ICC defendant pleaded guilty of the crimes he was accused of.

However, another event that took place during the crisis of 2012 in Timbuktu flew under the radar. This event is the book smuggling that took place from Timbuktu to Bamako, Mali’s capital city, to safeguard cultural property. The story is persuasively narrated by Charlie English. According to him, records read that around 4,200 manuscripts were, in fact, burned by the terrorist group and librarians did as much as they could to protect the manuscripts they cared or through burial and smuggling. However, English realizes that the operation of transportation of said manuscripts had been exaggerated. He found a tendency by private investors to inflate the number of manuscripts in order to get donations. Previously, the collection of IHERIAB had been the recipient of large investments for several international projects that directed money through private owners because of their efficiency. In 2012, when jihadists arrived to Timbuktu, a journalist reported that many manuscripts had been burnt, which then turned out not to be true. Nonetheless, Abdel Hader Kaidara raised several hundreds of thousands of dollars to smuggle the manuscripts to Bamako. the conflict in Timbuktu was framed as a cultural rights issue. Why was this effort successful? Why in Timbuktu?

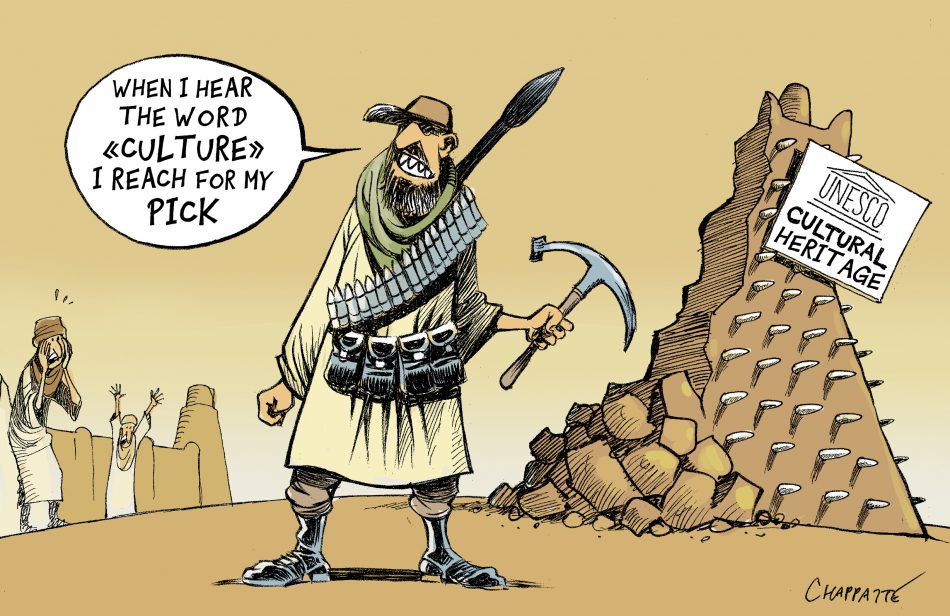

Source: Chapatte

Cultural rights and their importance

The Malian case of 2012 has set a precedent for the future of cultural rights. In 2016, Al Mahdi was convicted for the destruction of cultural sites in Timbuktu as war crimes. This has raised the status of cultural rights and increased their importance – to the point where they are central to some conflicts, such as in Mali. Some believe in the importance of cultural rights in preserving local cultures and argue that they should be protected more firmly, especially under the United Nations doctrine of Responsibility to Protect (R2P). R2P can be interpreted as protecting cultural rights within the larger framework of human rights. Since cultural patrimony belongs to and concerns all humankind, its universal value transcends state borders. However, this conception of the centrality of human rights fails to grasp the wider issue at hand and all the complexities behind conflicts where cultural sites are at risk. While heritage is key to preserving local cultures and people attach meaning to ancient traditions and places, there are other human rights that should be protected and guaranteed more vehemently than cultural heritage, especially in a context where the cultural heritage’s value is questioned.

What truly matters

Not only is Timbuktu a complex sociopolitical and socioeconomic site where poverty is a troubling issue for which there is no pathway for a clear solution, but the crimes committed in 2012 by the jihadist group Ansar Dine have further complicated the situation. Nonetheless, these layers of conflict were not portrayed as such in international media, which mainly focused on cultural damage in Timbuktu. Amnesty International and the International Federation for Human Rights expressed concern about the ICC trial in 2016 that condemned Al-Mahdi and how it did not include the judging of crimes such as rape, murder and torture. This lack of focus on people’s security and safety conflicts with our understanding of basic human dignity. We do value, as we should, art and heritage. However, how far are we willing to go? The protection of life and dignity should come first when we decide how to deal with a complex conflict.

Thus, a different approach and different framing need to be set in order to promote human security in cases where cultural heritage has been damaged. Instead of focusing international discourse on cultural destruction, a broader approach should be taken. The first step could be to restructure the programs that protect cultural heritage in Timbuktu. Instead of leaving cultural protection in the hands of private organizations that seek profit, a combination of state-led and UN-funded programs should be implemented to seek the development of the region in conjunction to the promotion of culture. For example, by taking the needs of the local population into account, consulting them about their needs in respect to culture and promoting their participation in the restoration of art and heritage in ways that enhance their economic development. Locals should decide how they funnel the money they are given by UNESCO for the protection of their own cultural heritage, and with their own economic enhancement, cultural protection would also increase. Moreover, if the fundraising system for preserving local cultures is changed into a broader development initiative as outlined above, the simplified discourse that reduces conflict into a mere cultural issue would disappear – or at least become more nuanced. Human security could be put at the forefront of international worry: protection firstly of the integrity of human life and secondly of the cultural heritage of local cultures could be established.