Just last month, President Filipe Nyusi signed a peace accord with Renamo, a former rebel movement, and proclaimed that it would “allow for the long-lasting peace that all Mozambicans have so longed for.” Unfortunately, not long after ending one armed movement, Mozambique is facing yet another insurgency in the northern province of Cabo Delgado. However, the ambiguity revolving around the motives and group dynamics of this emerging insurgency group is unique: the group has not released official objectives or demands while terrorizing civilians. Meanwhile, the Mozambican government contradicts itself by claiming the violence is committed by ordinary criminals one day, and then claiming that the group is representative of the spread of global jihadism the next.

Locally, the group is known as al-Shabaab or Ahlu Sunnah Wa-Jamâ (ASWJ), which roughly translates to “adherents of the prophetic tradition.” In Cabo Delgado, there have been unknown assailants swarming villages, murdering civilians, and setting fire to homes and businesses. The attacks have displaced more than 1,000 citizens.

Without properly addressing the underlying grievances in Mozambique, foundational factors that have created social volatility will continue to encourage insurgency organizations to rise in the Cabo Delgado region. The Mozambican government must show their commitment to serve their constituents by addressing the high youth unemployment rates, resolving the unjust resettlement of locals by foreign corporations, and ensuring that security forces operate under their appropriate jurisdiction.

Cabo Delgado: The Richest Region With The Poorest People

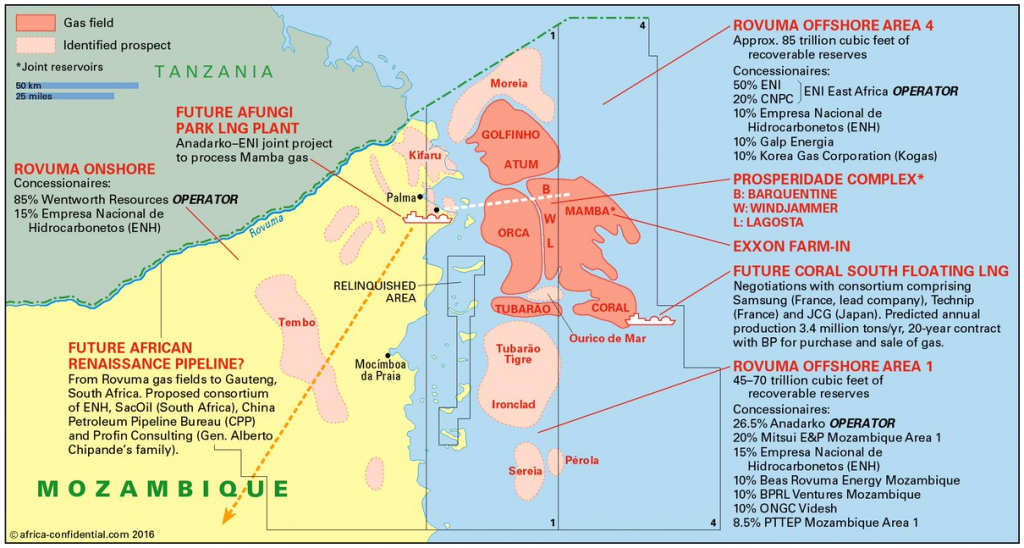

In 2011, natural gas fields worth up to an estimated $150 billion were discovered about 30 miles off the coast of Cabo Delgado. Additionally, it is the world’s largest ruby source; in 2014, rubies from Montepuez Ruby Mining sold for $407 million. Despite its wealth of natural resources, the Cabo Delgado province is the poorest in Mozambique and has high rates of youth unemployment.

Many residents are frustrated that their region’s wealth is benefiting the political elite of the nation rather than the local region itself. A study conducted by the UN University World Institute for Development Economics Research in found that 90 percent of households were deprived in the Northern Provinces, while less than 10 percent of households in southern provinces were considered deprived. The geographic separation and economic differences of the wealthier and more developed southern regions have created a cultural “otherness” among residents. Interviews with local residents by IESE, an independent and non-profit Mozambican organization that conducts research on social and economic development in Mozambique, revealed that residents’ attempts to petition the government for improved economic opportunities were ignored. Instead, they were accused of being members of Renamo. All of these factors provide prime recruitment for ASWJ.

Image Source: Future Directions International

Fueled by Corporate and Government Abuse

Abuses by Gemfields, a ruby mining concession, fueled the first insurgent attack. Gemfields allegedly destroyed miners’ property, tortured, and killed residents to overtake the Montepuez District, which is one of the world’s largest ruby reserves. ASWJ attacked a police station shortly after in October of 2017. The Mozambican government responded to the attack by closing mosques and detaining nearly 300 people without proper charges. Security forces arrested young men who had not fled after the attacks and took them to “temporary screening” in makeshift barracks. Security forces violated Mozambican and international law by not charging the men, legally presenting them before a judge, nor providing them access to their lawyers or family members.

Again in February 2019, ASWJ killed one Anadarko Petroleum Corp worker and injured six others in two attacks near the construction site for its liquified natural gas project. Although natural resource extraction projects provide massive economic growth for countries and the foreign corporations, few jobs have been created for the local populace. Arrested suspects reported to be opposing gas drilling. Further attacks on foreign companies who are exploiting the natural resources of the region affirm that the group is not a global jihadist group, but rather a group composed of unemployed and alienated individuals seeking to satisfy basic economic and social necessities.

Youth unemployment is not a new challenge for the Mozambican government. In 2012, 70 percent of Mozambicans under the age of 35 were without stable employment. Unemployed young men are especially embittered because they cannot pay the bridewealth required for marriage, and consequently, cannot make the traditional transition to adulthood. In May of 2018, hundreds of young people held a demonstration demanding jobs in fossil fuel companies. They were protesting current jobs in those industries being held by foreigners instead of locals. The limited alternatives for unemployed youth leave them vulnerable to recruitment by insurgents.

The highest priority for the Mozambican government is to strengthen the agricultural sector by including rural infrastructure and basic technologies, such as pesticides and fertilizer. Another way to provide more opportunities is to foster entrepreneurship in informal jobs, which currently have heavy regulations and complex rules.

Resettlement of Locals

The Anadarko company claims they are committed to delivering resettlement to “restore and improve livelihoods and standard of living.” A few of the group’s official resettlement commitments include compensating people affected by the project and assisting people to limit the disruption to their daily lives. Unfortunately, many resettled Cabo Delgado community leaders complained of inadequate payment for land. Other fishermen are being settled inland near communities they do not know and cannot operate in. Women farmers are concerned about losing their families’ lands and consequently not being able to feed their children. Farmers complained that Anadarko informed them that, regardless of how many hectares of land they initially owned, each farmer would be receiving 5 hectares of land maximum as compensation. The resettlement efforts are only heightening negative sentiments and security risks. Interviews in the region revealed that some of the resettled youth have decided to join ASWJ.

Besides removing people from their homes and reducing their means to survive, resettlement adds to the instability across Mozambique. ASWJ have also conducted revenge killings motivated by disputes over land access between those being resettled and the Mozambicans who historically settled the area and possess rights.

Mozambique’s legal land tenure system also makes it difficult for people to establish themselves in their new homes even if they adjust to that region’s agriculture or farming system. Under the land tenure system, the state owns the land and the occupants of the land have the right of usage and improvement. However, in reality, land rights are vulnerable to capture and abuse by elites who are supported by the state. Although Mozambique’s 1997 Land Law asserts that individuals and communities can obtain rights to land even without formal documentation of those rights, rural residents are unable to secure their rights in practice against third parties. This system adds to the obstacle resettled people face in making long-term investments in their land or engaging in negotiations with private corporations.

President Nyusi opened up that he would be open to negotiate with the insurgents like he did with Renamo, but only “if they show their faces.” Perhaps before negotiating with insurgencies to stop their violent acts, President Nyusi should hold his own security forces accountable for their abuses against Mozambican civilians. In January 2019, Amade Abubacar, a journalist, was arrested for reporting on the violence occurring in Cabo Delgado, and there have been an increasing number of arbitrary arrests of journalists. The Mozambican National Human Rights Commission also revealed overcrowding in prisons where defendants are being held so severe that prisoners are being forced to sleep standing up. Locals and NGOs have been questioning whether security forces are really there to protect the local citizens, especially after two people were killed during an insurgent attack despite a battalion being stationed close by. Security forces should cease their mass arrests against civilians because these actions only act to undermine their ability to cooperate with Cabo Delgado residents and hinder their ability to fight the insurgents.

Resource Curse or Blessing?

The insurgents threatenedMozambique’s first election after reaching a peace accord with Renamo, which is now the largest opposition party, as people were afraid to go to polling stations due to the violence. After President Nyusi was re-elected earlier this month, the opposition is now calling for the results to be annulled. Alice Mabota, a human rights campaigner who ran briefly as an independent until her candidacy was blocked, called out the international community for being bystanders because “oil and gas speaks louder than just and fair elections.” Even if just for the sake of protecting their precious natural gas reserves, the Mozambican government should focus on quelling the insurgency that is impeding the progress of their projects. Long term, while the insurgency is still in its beginnings with no clear organization or sponsors as of now, then the Cabo Delgado region may be doomed to the same fate as the same natural resource rich Niger Delta region that has been plagued by conflict between foreign oil companies and ethnic groups who feel they are being exploited since the early 1990s.

Featured Image Source: Financial Times