By Harjot S. Dhindsa

During the demise of the British Empire in the South Asian subcontinent in the latter half of the twentieth century, a policy of transferring power through Partition was adopted. The year 1947 saw the inception of two countries carved out of what was notoriously referred to as the British Raj: India and Pakistan. The former whose population was majority-Hindu and the latter whose population was majority-Muslim. As the British forces were devastated economically by World War II, they saw no long-term imperative to keep India and, rather, saw a benefit in making all of South Asia a partner of Britain. However, in the chaos that arose after the hastened withdrawal of the British, promises made by the Indian state through a dialogue of bringing consensus-based policy to minorities of India were abandoned, delayed, and objectively broken. [1] Moreover, demands that were promised to be met in a free and independent India were repeatedly denied when questioned by Sikhs of Punjab and Muslims of Jammu-Kashmir (both regions are located in the north of India). [2] Therefore, the British facilitated consensus of 1947 was flawed as it possessed no system of checks and balances or accountability on the promises made by the Indian state to its minority communities. [3] This manifested in the lack of sincere consensus from the Indian state in the Partition’s aftermath — a process that was and remains ineffective in its execution of addressing long-delayed concerns of Punjabi Sikhs and Kashmiri Muslims. The negligence shown on behalf of the Indian state, ingrained in the failed British consensus, continues to remain the root cause of the genocide, loss of natural resources, human rights violations, and deprived religious freedoms that both of India’s minority-communities experienced in the latter decades of country’s history. [4]

In the pre-Partition era, the leaders of the Indian National Congress, Mohandas Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, had initiated several talks to ensure that the territorial domain of Jammu-Kashmir and Punjab would, at the bare minimum, temporarily go to India and not Pakistan. To safeguard this alliance, the leaders of these northern regions of present-day India were given the assurance of fulfillment for specific agreed-upon demands by Gandhi and Nehru. For Jammu-Kashmir, it was the freedom to exercise the right to self-determination (reserved under international law) to confirm the final status of Kashmir as an independent country or, at least, an integral part of India/Pakistan. For Punjab, it was the promise of safeguarding greater autonomy for the region’s Sikh majority, as it’s people sacrificed the most lives in India’s freedom struggle. Sikh political factions within Punjab had also given up their demand of Punjab becoming an independent country in exchange for joining India where their rights to freedom and liberty were claimed by Nehru and Gandhi to be better ensured. Regardless of the consensus reached through dialogue (under British oversight), the assurance brought to these minority populations by Gandhi and Nehru before Partition was broken by the same leaders who led administrations right in its aftermath. [5]

Calls for a United Nations-sponsored referendum in Kashmir and demands for greater autonomy in Punjab were at first denied and then clamped down by force. [6] The following year in April 1948, the U.N. Security Council passed Resolution 47 which called for a referendum by the Government of India to determine the final status of Jammu and Kashmir. [7] After 1947, Punjab (majority Sikh) and Kashmir (majority Muslim) became two of the only territorial occupations in India that were majority non-Hindu. [8] Possibilities of meeting already agreed-upon demands would have been the most viable for India’s leadership in establishing peaceful and long-term allyship between these two regions, but for the objective of appeasing the majority-Hindu population of India, the Indian state considered it better to reap political benefits from engaging in violence on the country’s minorities. Decades after the Partition of 1947, Punjab and Kashmir faced government suppression, state-sponsored extrajudicial killings, and continual silence or denial for their demands. [9] Circumstances only proliferated after Partition by the sustained repressionary policy blunders made by the Indian state which ultimately resulted in mass human rights violations [10], occurrences of several phases of genocide against Sikhs and Muslims residing in India, and the present-day Indian domestic policy which normalizes a culture of Hindu nationalism. [11]

The bulk of the pre-Partition policy consensus was constructed through dialogue between both Punjabi Sikh representatives (from Shiromani Akali Dal) and Mohandas Gandhi and Jawarlahal Nehru (from the Indian National Congress) which was perceived to be mutually beneficial to the minority leadership at that time. Gandhi and Nehru were at the forefront of deciding and ensuring these promises to Punjabi Sikhs at conferences and then underlining them at the negotiating table. In one of the earliest resolutions passed by the Congress party in the Lahore session of December 1929, during which Jawaharlal Nehru was present and Mohandas Gandhi read them out loud, it was recorded that, “…as the Sikhs in particular, and Muslims and other minorities, in general, have expressed dissatisfaction over the solution of communal questions proposed in the Nehru Report, this Congress assures the Sikhs, the Muslims and other minorities that no solution thereof in any future constitution will be acceptable to the Congress that does not give satisfaction to the parties concerned.” In repeated attempts to win over the confidence of the cautious Sikhs in general (who were collectively weary of the rights they would hold in an independent India, independent Pakistan, or even an independent country of their own), at a convention in Delhi on March 19, 1931, Mohandas Gandhi implored that, “I ask you to accept my word…and the resolution of the Congress that it will not betray a single individual, much less a community…our Sikh friends have no reason to fear that it would betray them. For, the moment it does so, the Congress would not only thereby seal its doom but that of the country too. Moreover, Sikhs are a brave people. They know how to safeguard their rights by the exercise of arms if it should ever come to that.”[12] In a cruel irony, Gandhi’s words would become true during the 1980s-90s, which was the era in which groups of militant Punjabi Sikh youth took to arms and political assassinations to make their demands heard by the Indian state. [13]

During the absolute near of Partition and the transfer of power between the British Empire to Pakistan and India, Jawaharlal Nehru reaffirmed the rhetoric being put forth to the Sikhs on the table. [14] On July 6, 1946, to an All India Congress Working Committee Convention at Calcutta that, “The brave Sikhs of the Punjab are entitled to special consideration. I see nothing wrong in an area and a set-up in the North where in the Sikhs may also experience the glow of freedom.” On December 9th, 1946, at the first meeting of the Constituent Assembly of India, it was said in the first resolution that, “Adequate safeguards would be provided for minorities… It was a declaration, a pledge and an undertaking before the world, a contract with millions of Indians, and, therefore, in the nature of an oath, which we must keep.” [15] Apart from [16] affording protection to the freedom of religion of Sikhs in Punjab, promises were also made that the Indian constitution would respect the guidelines of Riparian water rights and, therefore, give Punjab the primary authority over the waters running through their land (as Punjab was and is majoritarian a land of farmers). In addition to this, it was also promised that the indigenous language of the land, Punjabi, would be recognized as the official language of Punjab. [17]

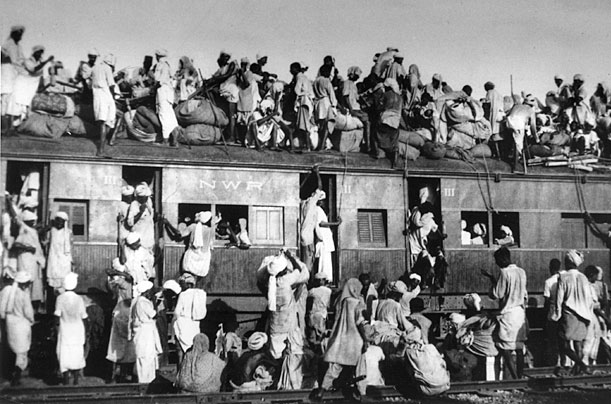

Due to flaws in the British facilitation of the consensus procedure of establishing no system of accountability or checks and balances for the promises made to the minority-communities of India, trust was breached from the Indian state when promises that were stressed so significantly in pre-Partition talks were being sidelined and then fully denied in a free India. During Partition, Punjab was cut in half: East Punjab to Pakistan and West Punjab to India. Most of the historical sites of the Sikhs were left in a radius of only a few miles of what now had become Pakistan, as Sikhs were forced out of Pakistan to India with communal riots. [18] The Radcliffe line, which became the official borders of India and Pakistan, cut through the indigenous homeland of the Sikhs and hence most casualties of this largest mass migration in human history occurred in Punjab. Nearly 10 to 12 million had crossed the boundaries of India and Pakistan [19] and close to 500,000 people lost their lives due to the massacres that were led by mobs of Hindus and Sikhs rallying against Muslims and mobs of Muslims rallying against Sikhs and Hindus.

In 1949, another breach of trust took place when Sikh representatives of the National Constituent Assembly [20] protested and did not give their signatures to the final draft of India’s constitution because Article 25B of the document (to this day) labeled all Sikhs to be construed as the part and parcel of the Hindu community when pertaining to legal matters. [21] Recognition of the independent and separate identity of the Sikhs was and is still denied in the country’s constitution. During this meeting on November 21, 1949, Hukam Singh, the Sikh representative, declared to the Constituent Assembly that, “Naturally, under these circumstances, as I have stated, the Sikhs feel utterly disappointed and frustrated. They feel that they have been discriminated against. Let it not be misunderstood that the Sikh community has agreed to this [Indian] Constitution. I wish to record an emphatic protest here. My community cannot subscribe to this historic document.” In 1955, India’s accordance with Punjab’s riparian water [22] rights was broken. Punjab ( Punj meaning “five” and Aab meaning “rivers”; the land of five rivers), was stripped of its authority to decide what to do with its water without any federal interference. Multiple dams were made despite protests and the illegal diversion of Punjab’s only natural resource took place under the blatant violation of international law and the Indian Constitution itself. [23] Immediately after 1947 and until the State Reorganization Act of 1965, Hindi, rather than Punjabi, is imposed to be the primary language of Punjab [24] — a possibility that the Sikh leaders of the pre-Partition era were constantly in fear of as it would, in their words, “eradicate Punjab’s political existence in its essence.” It was only after several protests and thousands of courted arrests that Punjab [25] got its recognition based on its language, which other states of India received without any hardships. While all states of India were created on linguistic boundaries, Punjabi was among the only languages of India that were denied their statehood. [26] Even after the official recognition of Punjab as a Punjabi speaking state [27], it was received at a geographical compromise as Punjabi-speaking areas were labeled as Hindi-speaking areas to cut the state of Punjab to a fourth of its original size, shrinking the already minority presence of Sikhs in India. [28]

Regarding the stakeholder analysis, the stakeholders in the specific consensus procedure of the Partition of India and Pakistan were the citizens of British occupied Kashmir, citizens of British occupied Punjab, citizens of the rest of India, and citizens of Pakistan (as they suffered the most). For political stakes, it was the leaders of the Indian National Congress (for Hindus, notably Jawaharlal Nehru and Mohandas Gandhi), Leaders of the All India Muslim League (for Muslims, notably Mohommad Ali Jinnah), Leaders of the Shiromani Akali Dal (for Sikhs, notably Hukam Singh and Master Tara Singh), and the British Government (notably Lord Mountbatten). The citizens were stakeholders because they cared about the well-being of themselves (through safeguarding their environments, rights, religion, and statehood). The leading political factions were involved in the decision-making regarding this matter and were often leaning towards or advocating for the demands of their communities (Indian National Congress for an independent India, All India Muslim League for an independent Pakistan, and Shiromani Akali Dal which shifted between fighting for an independent Punjab or joining the Indian union). It should be noted that, in contrast to their widespread involvement in global humanitarian crises today, there was little to no presence of international organizations like the United Nations, the U.S. government, or other human rights organizations. The British government was involved in the hastened process for the transfer of power (because of its lack of interest in running the South Asian colony after its economic deficit in WWII). Additional, comparably minor, stakeholders include British citizens for their involvement in the global dialogue, local British state authorities to overlook the violent aftermath of the Partition, and the organizers of refugee camps throughout Punjab to assist the violent-ridden refugees that came from Pakistan. However, the citizens of South Asia and Britain held little to no power in this consensus procedure — even though the citizens of Pakistan and India were the most impacted — because it was often the leaders of the appointed parties from the various communities that raised concerns on their behalf.

This lack of direct assertion by the citizenry is reflected by the extent of reprisal and the sense of betrayal that was felt by the Punjabi Sikh public. Compared to the Sikh representative body, the Indian National Congress and All India Muslim League held more political leverage because of the population they represented and their relatively clearer demands made to British authorities. The British government held the highest power in regards to this [29] conversation because they served as the facilitators in this consensus procedure and failed in establishing a system of accountability for the rights promised to minority-communities of India before Partition. Local British authorities and organizers of refugee camps also held little to no powers, because their involvement was enacted only in the aftermath of Partition. The conflicting interest was the battle between the more territorial expansion of Pakistan and India, out of which the Sikhs and Kashmiris are still used as pawns. Overlapping interests were the rights denied to Kashmiris and Punjabis — and their shared fight against them. The success of the consensus procedure was only for the governments of India and Pakistan, as even after the violent toll on the people, the Indian National Congress and All India Muslim League were satisfied as they completed their decades-long struggles for advocating independence from Britain. The British received the most flack for the violent aftermath of the Partition [30] and the negligence shown in the consensus procedure of establishing a system of checks and balances on the Indian state (should they ever execute on the promises made). For citizens of Punjab — who were members of one of the most impacted communities by the violent aftermath of the Partition — the consensus procedure of 1947 continued to be the root cause for their denial of rights and demands from the Indian state. [31]

In hindsight, we can observe that if a system of accountability was kept intact, meaning that if Kashmir was given an opportunity to self-determine and demands of greater autonomy in Punjab were met (as promised to its people upon Partition), calls for breaking up modern-day India would have not been so profound. On consensus moving forward, there has been a historical continuity in Indian domestic policy that appears to be rooted in prejudice and hatred towards minority-communities. To heal the damage they have caused, reconciliation [32] should be observed for the Punjabi and Kashmiri lives lost due to state repression in the aftermath of a free India. The issues and demands that the Punjabi and Kashmiri people remain the same and pertaining proposals to solve those grievances still require improvement. [33] Sikhs are still construed as Hindus in the Indian constitution and Punjab’s excessive water diversion is creating districts in Punjab whose populations will go extinct in the next two decades. Due to unsolved complications of Indian independence, the incremental genocide of the [34] Sikh and Kashmiri people in India has continued unabatedly but remains to be acknowledged. With acknowledgment, the Indian government will open a new door to the long-delayed demands of these minorities since Partition. Instead of treating Punjab and Kashmir as colonies, India should look towards reviving dialogue and consensus between their people through executing the promises made by India’s independence leaders before Partition.

Endnotes

- Brass, Paul R. “The Partition of India and Retributive Genocide in the Punjab, 1946-47: Means, Methods, and Purposes 1.” Journal of Genocide Research 5, no. 1 (2003): 71–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520305657.

- Dhillon, G. S. Truth about Punjab: SGPC White Paper. Amritsar: Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee, 1996.

- Singh, Kapur. Betrayal of the Sikhs. Delhi: Akali Dal, Delhi State, 1966.

- Axel, Brian Keith. The Nations Tortured Body: Violence, Representation and the Formation of a Sikh Diaspora. Durham (N.C.): Duke University Press, 2001.

- Singh, Kapur. Betrayal of the Sikhs. Delhi: Akali Dal, Delhi State, 1966.

- Dhillon, G. S. Truth about Punjab: SGPC White Paper. Amritsar: Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee, 1996.

- Pettigrew, Joyce. The Sikhs of the Punjab: Unheard Voices of State and Guerrilla Violence. London: Zed Books, 1995.

- “UNSCR Search Engine for the United Nations Security Council Resolutions.” UNSCR. Accessed November 1, 2019. http://unscr.com/en/resolutions/47.

- Dhillon, G. S. Truth about Punjab: SGPC White Paper. Amritsar: Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee, 1996.

- Ibid.

- Singh, Gurharpal. “Hindu Nationalism in Power: Making Sense of Modi and the BJP-Led National Democratic Alliance Government, 2014–19.” Sikh Formations, 2019, 1–18.

- Bakshi, S. R., and Rashmi Pathak. Punjab through the Ages. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons, 2007.

- Dhillon, G. S. Truth about Punjab: SGPC White Paper. Amritsar: Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee, 1996.

- Mahmood, Cynthia Keppley. Fighting for Faith and Nation: Dialogues with Sikh Militants. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997.

- Sidhu, Aman, and Inderjit Singh Jaijee. Debt and Death in Rural India: the Punjab Story. Thousand Oaks: Calif., 2011.

- Dhillon, G. S. Truth about Punjab: SGPC White Paper. Amritsar: Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee, 1996.

- Chawla, J. K., S. D. Khepar, S. K. Sondhi, and A. K. Yadav. “Assessment of Long-Term Groundwater Behaviour in Punjab, India.” Water International 35, no. 1 (March 2010): 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060903513502.

- Sekhon, Awatar Singh, and Dilagīra Harajindara Siṅgha. India Kills the Sikhs. Edmonton, AB: The Sikh Educational Trust, 2016.

- Siṅgha Kirapāla. The Partition of the Punjab. Patiala: Publication Bureau, Punjabi University, 1989.

- Siṅgha Kirapāla. The Partition of the Punjab. Patiala: Publication Bureau, Punjabi University, 1989.

- “The Constitution of India.” Accessed November 2, 2019. https://www.india.gov.in/sites/upload_files/npi/files/coi_part_full.pdf.

- Dhillon, G. S. Truth about Punjab: SGPC White Paper. Amritsar: Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee, 1996.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Singh, Joginder. “Sikhs in Independent India.” Oxford Handbooks Online, March 2013. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199699308.013.016.

- Dhillon, G. S. Truth about Punjab: SGPC White Paper. Amritsar: Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee, 1996.

- Ibid.

- Sekhon, Awatar Singh, and Dilagīra Harajindara Siṅgha. India Kills the Sikhs. Edmonton, AB: The Sikh Educational Trust, 2016.

- Singh, Kapur. Betrayal of the Sikhs. Delhi: Akali Dal, Delhi State, 1966.

- Dhillon, G. S. Truth about Punjab: SGPC White Paper. Amritsar: Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee, 1996.

- Singh, Joginder. “Sikhs in Independent India.” Oxford Handbooks Online, March 2013.

- Axel, Brian Keith. The Nations Tortured Body: Violence, Representation and the Formation of a Sikh Diaspora. Durham (N.C.): Duke University Press, 2001.

- Ibid.

- Dhillon, G. S. India Commits Suicide. Chandigarh: Singh & Singh Publishers, 2004.

Be First to Comment