Note: A shorter version of this essay appeared in a special issue of Proteus: A Journal of Ideas on the subject of Memory (Vol. 19, No. 2, Fall 2002).

Psychologists usually define memory as knowledge stored in the mind, a storage that is physically implemented somehow in the brain. Memory is an extremely important cognitive faculty, because it forms the cognitive basis for learning. Without a way of storing mental representations of the past, we have no way of profiting from experience. But more important, memory frees us from the tyranny of perception, allowing behavior to be guided by the past as well as the present. J.M Barrie, the author of Peter Pan, once wrote that God gave us memory so we could have roses in December. Along with consciousness, intelligence, and language, the ability to represent and reflect on the past is the basis for human freedom and dignity.

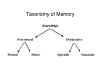

The knowledge stored in memory comes in a

few basic forms (Anderson, 1976; Tulving, 1983). Procedural

knowledge comprises our repertoire of rules and directions

for skilled action, while declarative knowledge consists

of factual knowledge about the world. Procedural knowledge can

be further subdivided into cognitive and motor skills, while

declarative knowledge can be classified into episodic and

semantic memory. Episodic memory is autobiographical memory for

one's own actions and experiences, while semantic memory is more

or less generic, abstract knowledge, like a mental dictionary,

not tied to any particular event. When most people speak

of "memory" they mean episodic memory, and that is what I mean

in this essay as well.

The knowledge stored in memory comes in a

few basic forms (Anderson, 1976; Tulving, 1983). Procedural

knowledge comprises our repertoire of rules and directions

for skilled action, while declarative knowledge consists

of factual knowledge about the world. Procedural knowledge can

be further subdivided into cognitive and motor skills, while

declarative knowledge can be classified into episodic and

semantic memory. Episodic memory is autobiographical memory for

one's own actions and experiences, while semantic memory is more

or less generic, abstract knowledge, like a mental dictionary,

not tied to any particular event. When most people speak

of "memory" they mean episodic memory, and that is what I mean

in this essay as well.

| Episodic memory is one's memory for

having had fish for dinner last Thursday.

Semantic knowledge is one's knowledge that fish are cold-blooded creatures with scales and fins. Procedural knowledge is one's knowledge of how to hold a knife and fork. |

For most of its history, psychology has been concerned with episodic memory. In the verbal-learning paradigm invented by Ebbinghaus (1885/1964), each list of nonsense syllables, and for that matter each individual nonsense syllable, constitutes a separate episode of experience, to be remembered in the context of other episodes; the same is true for the words, pictures, and sentences that constitute the stimulus materials employed in most contemporary studies of memory, more than a century later.

And for most of its history, psychology has studied episodic memory as if it were a static object. In Ebbinghaus's pioneering book, Uber das Gedachtniss, memory is clearly a noun, a thing to be studied. Operating in this tradition, the cognitive psychologist Gordon Bower (1967) defined a memory trace as a bundle of features describing an event. Similarly, in traditional neuroscience, the engram (a term coined by the German biologist Richard Semon), is the change in neural tissue corresponding to a memory: it is the thing for which the pioneering neuroscientist Karl Lashley (1957) searched in vain for his whole career.

Now it's probably already clear that I'm

going to criticize this trend among psychologists, but in the

interest of full disclosure I also want to make clear that I've

done this myself, in discussing the structure of

autobiographical memory within the framework of a generic

network model of memory. My view of episodic memory begins with

an event node, representing a propositional description

of an event like John Anderson's famous sentence:

Now it's probably already clear that I'm

going to criticize this trend among psychologists, but in the

interest of full disclosure I also want to make clear that I've

done this myself, in discussing the structure of

autobiographical memory within the framework of a generic

network model of memory. My view of episodic memory begins with

an event node, representing a propositional description

of an event like John Anderson's famous sentence:

The hippie touched the debutante.

Each element of this proposition is linked to semantically related meaning-based knowledge, such as the fact that hippies wear tie-dyed T-shirts and drive VW buses while debutantes wear evening gowns and drive Porches, as well as to perception-based knowledge such as what hippies and debutantes look like.

But while a sentence such as The hippie

touched the debutante describes a specific event, it isn't

yet an episodic memory: it's just a raw propositional fact. In

order to become an episodic memory, the event node has to be

linked to other propositions representing episodic context -- context

nodes that represent the time and place at which the event

occurred:

But while a sentence such as The hippie

touched the debutante describes a specific event, it isn't

yet an episodic memory: it's just a raw propositional fact. In

order to become an episodic memory, the event node has to be

linked to other propositions representing episodic context -- context

nodes that represent the time and place at which the event

occurred:

The hippie touched the debutante in People's Park on Thursday.

But this still isn't an episodic memory:

it's just a historical fact about a people at a particular place

and time, like Columbus discovered America in 1492. To

create an episodic memory, and autobiographical

memory (with the emphasis on auto), the event node must

be linked to a mental representation of the self as the agent or

patient of some action or the stimulus or experiencer of some

state. Thus,

But this still isn't an episodic memory:

it's just a historical fact about a people at a particular place

and time, like Columbus discovered America in 1492. To

create an episodic memory, and autobiographical

memory (with the emphasis on auto), the event node must

be linked to a mental representation of the self as the agent or

patient of some action or the stimulus or experiencer of some

state. Thus,

I saw the hippie touch the debutante

or

I was outraged when the hippie touched the debutante,

or even

I was the hippie who touched the debutante.

Somewhere, somehow, there's got to be an I

or a me in the memory. Without this critical link to the

self, there's no autobiographical memory.

Somewhere, somehow, there's got to be an I

or a me in the memory. Without this critical link to the

self, there's no autobiographical memory.

So there you have a sense of an episodic memory as an object: a thing, a trace, an engram, which contains information about an event, its context, and its relationship to the person who has the memory.

The notion of memories as things is clearly reflected in the stage analysis of memory familiar from early cognitive psychology:

| Memory trace are things to be encoded, stored, and retrieved. | |

| Encoding makes memories available in storage , and retrieval gains access to available memories. | |

| Forgetting reflects a failure of availability or accessibility caused by a failure at one or more of these processing stages. |

Stage analysis, in turn, is based on the library metaphor of memory:

| Memories are like books to be purchased, cataloged, and placed on shelves. | |

| When we want the information stored in memory, we look up the location of the book, take the book down from the shelf, and read it. | |

| If the book has been improperly cataloged or shelved, we may not find it, even if it is present in the library | |

| Even if it has been properly cataloged and shelved, it may have been checked out by someone else. | |

| Otherwise, the book may have been stolen; or it may have been eaten away by worms. |

All of this is well and good, and it's been enormously heuristic for the study of memory. For one thing, pursuing the notion of a memory as a thing has yielded a surprisingly small set of principles by which we can understand the causes of remembering and forgetting (Kihlstrom & Barnhardt, 1993):

| Elaboration: Memory improves when an event is related to pre-existing knowledge. | |

| Organization: Memory improves when events are related to each other. | |

| Time-Dependency: Memory fades with time. | |

| Interference: The cause of forgetting is competition among available memories, not the loss of memories from storage through decay or displacement. | |

| Cue-Dependency: Memory improves when the environment provides richly informative retrieval cues. | |

| Encoding Specificity (also known as Transfer-Appropriate Processing): Memory is best when information processed at the time of retrieval matches information processed at the time of encoding. | |

| Schematic Processing: Memory is better for events that match our expectations than for events that are irrelevant to them, but memory is best for events that violate our expectations. |

But it's not the only way to look at things.

A big shift in perspective was announced by Frederick C. Bartlett (1932), almost 50 years after Ebbinghaus published his book. It is evident in the very title of Bartlett's book: Remembering, and it is clear in Bartlett's first chapter, which is a scathing attack on poor old Ebbinghaus:

The results of the nonsense syllable experiments may throw light upon the... establishment and the control of [very special habits of reception and repetition], but it is at least doubtful whether they can help us see how, in general, memory reactions are determined.

For Bartlett, memory is not a thing, labeled by a noun, but rather an activity, labeled by a verb. Memories are things people have, but remembering is something people do. Referring back to the library metaphor, memory is not like a book that we read, but rather it's like a book that we write anew each time we remember. One's memory may be based on fragmentary notes supplied by the memory trace, but (as Jerome Bruner might have put it) remembering involves "going beyond the information given" there. In the famous "trash bag" scene of the film American Beauty (1999), one of the characters says that "video is a poor excuse, I know, but it helps me to remember". So it is with the memory trace, in Bartlett's view. The memory trace supports remembering, but it's not all there is to memory.

Bartlett's view adds a new Reconstruction Principle to our list of the operating principles in memory:

One's memory of an event reflects a blend of information contained in specific traces encoded at the time it occurred, plus inferences based on knowledge, expectations, beliefs, and attitudes derived from other sources.

In other words, remembering is more like making up a story than it is like reading one printed in a book. For Bartlett, every memory is a blend of knowledge and inference. Remembering is problem-solving activity, where the problem is to give a coherent account of some past event, and the memory is the solution to that problem.

In some sense, the conflict between Ebbinghaus and Bartlett was more apparent than real. Ebbinghaus knew perfectly well that nonsense syllables left something important out of memory, and Bartlett knew perfectly well that something like Ebbinghaus's methods were necessary for proper experimental research. And it's clear that reconstructive processes can be studied within the constraints of the traditional verbal-learning paradigm.

Consider, for example, the notion that there are two expressions of episodic memory: as defined by Daniel Schacter (1987), explicit memory entails conscious recollection of some past event, as in recall or recognition; by contrast, implicit memory is represented by any change in experience, thought, or action which is attributable to that event, as in repetition or semantic priming effects. Explicit and implicit memory can be dissociated such that we can observe priming effects in amnesic patients who cannot recall or recognize the prime. This has led some theorists to propose that explicit and implicit memory are mediated by separate and independent memory systems. It turns out, however, that explicit and implicit memory interact, so that subjects can strategically capitalize on implicit memory to support their performance on an explicit memory task.

The basis for this view lies in George Mandler’s (1980) two-process theory of recognition. According to Mandler, recognition is a judgment of prior occurrence which is based on two processes: familiarity, as when something you encounter "rings a bell", leading you to believe that you have encountered it before; and retrieval, or conscious recollection based on recovery of episodic trace information. Retrieval obviously constitutes explicit memory, while familiarity has the character of priming. But if recognition can be mediated by either familiarity or retrieval, then recognition ought to be possible in amnesia, provided that amnesic patients are encouraged to strategically capitalize on the perceptual and conceptual salience which comes with priming.

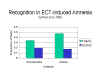

This point was made convincingly in a study by Jennifer Dorfman, a student of Mandler’s who spent time in my lab at Arizona. Dorfman worked with a group of psychiatric patients receiving electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for depression. It is well known that ECT produces both an anterograde and a retrograde amnesia affecting explicit memory but sparing implicit memory. In her experiment, the subjects studied a word-list immediately before receiving ECT; then their memory was tested in the recovery room by means of matched explicit and implicit tests.

For the explicit test, the patients were

presented with three-letter stems of list items and control

words, and asked to remember a word from the study list that

began with the stem. As expected, their performance was very

poor. For the implicit test, the patients were presented with

the same sorts of stems, but now they were asked to generate the

first word that came to mind. On this task, the subjects showed

a priming effect, completing more critical than neutral stems

with the target word.

For the explicit test, the patients were

presented with three-letter stems of list items and control

words, and asked to remember a word from the study list that

began with the stem. As expected, their performance was very

poor. For the implicit test, the patients were presented with

the same sorts of stems, but now they were asked to generate the

first word that came to mind. On this task, the subjects showed

a priming effect, completing more critical than neutral stems

with the target word.

The subjects also received a test of

recognition. For half of the items, they were asked to adopt a

conservative criterion, endorsing an item only when they were

absolutely sure that it had been on the study list. For the

remainder, they were instructed to adopt a more liberal

criterion, saying "yes" if an item seemed familiar, even if they

were uncertain. There was much better recognition under the

liberal criterion, as might have been expected, but this

improvement was not merely an artifact of response bias, because

false alarms did not rise along with the hits.

The subjects also received a test of

recognition. For half of the items, they were asked to adopt a

conservative criterion, endorsing an item only when they were

absolutely sure that it had been on the study list. For the

remainder, they were instructed to adopt a more liberal

criterion, saying "yes" if an item seemed familiar, even if they

were uncertain. There was much better recognition under the

liberal criterion, as might have been expected, but this

improvement was not merely an artifact of response bias, because

false alarms did not rise along with the hits.

Here we have an interesting case in which, contrary to the claims of traditional signal-detection theory, sensitivity does indeed change with a shift in criterion. But the more important finding, in the present context, was that recognition improved -- provided that the patients were encouraged to capitalize on the feeling of familiarity that comes with priming. Recognition by familiarity is essentially a reconstructive, problem-solving process, in which people are trying to give the best possible account of the past, given all of the information available to them.

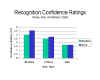

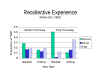

In fact, recent research on recollective experience, or the phenomenal experience of remembering, makes clear that the precise quality of the memory, and the person’s confidence in it, will depend on its informational base. I’m thinking, for example, of the distinction drawn by Endel Tulving (1985) between remembering, or one’s concrete awareness of the past (entailing what Tulving calls "autonoetic consciousness", knowing, or one’s abstract knowledge of the past (entailing what Tulving calls "noetic consciousness"), and doing, or memory as expressed in performance (entailing what Tulving calls "anoetic" consciousness).

John Gardiner (1988) has developed this distinction further, but while Tulving and Gardiner use the same "remember/know" vocabulary, they are talking about quite different phenomenal experiences. For Tulving, "knowing" is really knowing, one’s abstract knowledge of an event, based on something like semantic memory. Knowing our personal past, in this respect, is like knowing that Columbus discovered America in 1492. But Gardiner’s "knowing" is really feeling, an intuition that an event occurred, based on something like implicit memory.

So even though Tulving and Gardiner only distinguish between "remembering" and "knowing", there are actually three varieties of recollective experience, or memory "qualia": remembering, or conscious recollection of some past event; knowing, or abstract knowledge of that event; and feeling, an intuition that an event occurred.

Traditional experiments on remembering and knowing do not make this critical distinction between knowing and feeling, but a line of research by Mike Kim and myself has done so (Kihlstrom & Kim, 1998; Kihlstrom, Kim, & Dabady, 1996; Kim & Kihlstrom, 1997). Our studies involved an extension of the Tulving/Gardiner paradigm: in the typical experiment, subjects studied a list of words under a levels of processing manipulation; after a 24-hour retention interval they performed a yes/no recognition task. They were also asked to report their recollective experiences, which we illustrated by analogy to a multiple-choice test. Sometimes, you just know the answer; sometimes, you actually remember learning the material, such as where it appeared on a page in your textbook. And sometimes, an answer just "rings a bell", so you feel it must be the right choice.

If we look at overall recognition, we get

the expected levels effect.

If we look at overall recognition, we get

the expected levels effect.

But if we then distinguish among the

varieties of recollective experience, we get a dissociation by

level of processing: semantic processing favors remembering and

knowing, while phonemic processing favors feeling. In a series

of experiments, Kim and I have shown that feeling can be

dissociated from remembering and knowing by a number of factors

besides level of processing: amount of study, criterion shifts,

confidence levels, and response latencies.

But if we then distinguish among the

varieties of recollective experience, we get a dissociation by

level of processing: semantic processing favors remembering and

knowing, while phonemic processing favors feeling. In a series

of experiments, Kim and I have shown that feeling can be

dissociated from remembering and knowing by a number of factors

besides level of processing: amount of study, criterion shifts,

confidence levels, and response latencies.

But in all these experiments remembering

and knowing behave in pretty much the same way. Recently,

however, we have been able to dissociate remembering from

knowing by a somewhat boring task: 15 study-test cycles with a

20 item list, each study trial followed by a recognition test

and ratings of recollective experience. Memory improved

over trials, of course, but the most important changes had to do

with recollective experience. On initial trials, we see the

familiar mix of remembering, knowing, and feeling; but on later

trials, feeling drops out of the picture, and remembering is

replaced by knowing. By the end of the 15 trials, the subjects

aren’t remembering anything: they know the

contents of the study list, the way they know the list of state

capitals.

But in all these experiments remembering

and knowing behave in pretty much the same way. Recently,

however, we have been able to dissociate remembering from

knowing by a somewhat boring task: 15 study-test cycles with a

20 item list, each study trial followed by a recognition test

and ratings of recollective experience. Memory improved

over trials, of course, but the most important changes had to do

with recollective experience. On initial trials, we see the

familiar mix of remembering, knowing, and feeling; but on later

trials, feeling drops out of the picture, and remembering is

replaced by knowing. By the end of the 15 trials, the subjects

aren’t remembering anything: they know the

contents of the study list, the way they know the list of state

capitals.

The feeling of knowing is aptly described in the Rodgers and Hart song "Where or When", from their musical Babes in Arms (1937):

|

When you're awake The things you think come from the dreams you dream. Thought has wings, And lots of things are seldom what they seem. Sometimes you think you've lived before All that you live today. Things you do come back to you, As though they knew the way. Oh, the tricks your mind can play! |

|

It seems we stood and talked like this before. We looked at each other in the same way then, But I can't remember where or when. The clothes you're wearing are the clothes you wore. The smile you are smiling you were smiling then, But I can't remember where or when. |

|

Some things that happen for the first time, Seem to be happening again. And so it seems that we have met before, and laughed before, and loved before, But who knows where or when! |

Distinguishing between remembering, knowing, and feeling also sheds light on another phenomenon, the "associative memory illusion" (AMI) originally demonstrated by Deese (1959), and rediscovered and elaborated by Roediger and McDermott (1995). The illusion is induced by asking a subject to study a list of words, all of which are associates of an unstudied target item, known as the critical lure. For example, thread, pin, eye, sewing, sharp, and point are all relatively high-frequency associates of the word needle. The AMI occurs when subjects who have studied the items of the inducing list falsely remember having studied the critical lure, in this case needle, as well.

One popular explanation of the AMI is that presentation of the list items primes a representation of the semantically related critical lure, making it more likely to be accessed during retrieval. In a recent experiment conducted in my laboratory by Lillian Park and Katie Shobe (Shobe, Park, & Kihlstrom, 1999), subjects received auditory presentations of six lists, each consisting of 12 common associates to a critical lure: cold, sweet, bread, needle, dark, and slow, in a levels of processing manipulation. Following the presentation of all three lists, the subjects were surprised with tests of free recall and recognition. For the recognition test, the subjects made judgments on a four-point scale of confidence. If they gave an item a confidence rating of 3 or 4, indicating that they thought it was either probably or definitely old, they were asked to report on their recollective experience using the three-category system employed by Kim and myself.

On the recognition test, old items subject

to deep, semantic encoding received higher confidence ratings

than those subject to shallow, acoustic encoding, yielding the

familiar level-of-processing effect. Interestingly, level of

processing also influenced false recognition of the critical

lures. Items in both categories received higher confidence

ratings compared to the entirely new, unrelated lures. Note,

however, that the critical lures did not receive as high

confidence ratings as did the studied items. This is our first

clue that there is a difference between true and false recall.

On the recognition test, old items subject

to deep, semantic encoding received higher confidence ratings

than those subject to shallow, acoustic encoding, yielding the

familiar level-of-processing effect. Interestingly, level of

processing also influenced false recognition of the critical

lures. Items in both categories received higher confidence

ratings compared to the entirely new, unrelated lures. Note,

however, that the critical lures did not receive as high

confidence ratings as did the studied items. This is our first

clue that there is a difference between true and false recall.

Further evidence came from the ratings of recollective experience. The usual finding in these sorts of experiments is that the recollective experience associated with false memory is the same as that associated with true memory. This is a little puzzling, because while correct recognition can be mediated by episodic retrieval, false recognition must be mediated by priming-based familiarity. Unfortunately, earlier studies of recollective experience in false memory only distinguished between remembering and a fallback category of "knowing" which conflated genuine "knowing" with feeling.

When you make the tripartite distinction,

you get somewhat different results. True recognition of studied

items was overwhelmingly associated with an experience of

remembering, whereas false recognition of critical lures was

overwhelmingly associated with feelings of familiarity, not

remembering. So, the experiences of true and false recognition

are not phenomenally equivalent after all. This is as it should

be, if the illusion of memory represented by the false memory

effect is a product of priming-based feelings of familiarity,

rather than conscious recollection.

When you make the tripartite distinction,

you get somewhat different results. True recognition of studied

items was overwhelmingly associated with an experience of

remembering, whereas false recognition of critical lures was

overwhelmingly associated with feelings of familiarity, not

remembering. So, the experiences of true and false recognition

are not phenomenally equivalent after all. This is as it should

be, if the illusion of memory represented by the false memory

effect is a product of priming-based feelings of familiarity,

rather than conscious recollection.

In my view, each of these different varieties of recollective experience is based on the rememberer's access to different sources of information. In remembering, one gains access to a full episodic memory trace, including a raw description of the event in question, the spatiotemporal context in which it was situated, and some representation of the self as the agent or patient, stimulus or experiencer of the event. In knowing, self-reference is absent: one simply has the abstract knowledge that something happened at a particular time and place. In feeling, the person accesses at least a partial description of the event, but no episodic context, and no self-reference. Thus, the person's recollective experience varies, not with the strength of the underlying memory trace, but with the nature of the information on which the recognition judgment is based. One could develop a similar analysis of recall.

Actually, though, I think that there's more to memory than remembering, knowing, and feeling: there's also believing. This idea is a little confusing, because in philosophy belief is a general term for any representational mental state -- something which has a proposition as its content, and which combines with a motive to direct behavior. Memories, then, are just a special class of beliefs -- beliefs about the past, just as percepts are beliefs about the present. But I'm not talking about beliefs in the technical sense of philosophy: I'm talking about belief as the phenomenal basis of remembering: one's inference that an event occurred in the past -- an inference that is based on available world knowledge, including one's knowledge of oneself, in the absence of any recollection. Thus, if you were to ask me whether I ever swam in Skaneateles Lake, in upstate New York, I might well say "yes, I believe so", because I was born and raised in the Finger Lakes region, I know that I've swum in Keuka and Seneca Lakes, and my family had friends who lived in Skaneateles. But I don't remember ever doing such a thing.

Frankly, we've had trouble observing

remembering-as-believing in the laboratory. Initially, I thought

that we'd get it in the AMI paradigm, but I was wrong. In her

doctoral dissertation, Katie Shobe added a category of believing

to our usual mix of remembering, knowing, and feeling in the

false-memory paradigm. Katie replicated our basic finding, which

is that critical lures are less likely to be "remembered" than

old studied items, but we just didn’t see much evidence of

believing.

Frankly, we've had trouble observing

remembering-as-believing in the laboratory. Initially, I thought

that we'd get it in the AMI paradigm, but I was wrong. In her

doctoral dissertation, Katie Shobe added a category of believing

to our usual mix of remembering, knowing, and feeling in the

false-memory paradigm. Katie replicated our basic finding, which

is that critical lures are less likely to be "remembered" than

old studied items, but we just didn’t see much evidence of

believing.

However, we do see something like remembering-as-believing in autobiography, and in history. One of the interesting features of contemporary literature is the gradual displacement of the novel by the memoir. As the critic James Atlas wrote in the New York Times Magazine, "the triumph of memoir is now an established fact". Instead of reading fiction about ordinary people (the technical definition of a novel, as opposed to myth or legend), we now read nonfiction about ordinary people. (Click here to read Atlas' article.)

Interestingly, the novel itself emerged from earlier literary forms, which look a lot like autobiographies and histories. In English, for example, there are "memoir novels" like Defoe's Robinson Crusoe (1719) and Moll Flanders (1722), "epistolary novels" like Richardson's Pamela (1741), and "histories", like Fielding's Tom Jones (1749). By the 19th century, the familiar form of the modern novel had been established: an omniscient third-person narrative of ordinary people engaged in the ordinary course of everyday living. Now, it seems that we've come almost full circle: the memoir has displaced the novel as the literary genre of our age. We've returned to a first-person narrative of ordinary people in everyday life, but also with a kind of omniscience in which authors view earlier experiences in the light of later ones.

AA and the Return of the MemoirPerhaps one factor in the rise of the memoir is the popularity of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and similar support groups derived from it. A major aspect of participation is the sharing of a "narrative" of each member's involvement with alcohol. As one AA participant noted:

|

The poet Patricia Hampl notes this trend in her wonderful book on the memoir, I Could Tell You Stories (1999), which is subtitled Sojourns in the Land of Memory. There she recounts an experience in which her father took her for her first piano lesson. The passage goes on for a couple of pages, and there's quite a bit of detail, including the red "Thompson book" which I remember from my own piano lessons (and you probably do, too). She then writes:

For the memoirist, more than for the fiction writer, the story seems already there, already accomplished and fully achieved in history ("in reality", as we naively say). For the memoirist, the writing of the story is a matter of transcription…. The experience was simply there, like a book that has always been on the shelf, whether I ever read it or not…. On the day I wrote this fragment I happened to take that memory, not some other, from the shelf and paged through it. I found more detail, more event, perhaps a little more entertainment than I had expected, but the memory itself was there from the start. Waiting for me.

And then she drops the other shoe:

Wasn't it? When I reread the piano lesson vignette just after I finished it, I realized that I had told a number of lies.

It turns out that almost every detail in the memory is wrong, or at least questionable, right down to the least questionable thing of all: the red "John Thompson" piano book -- which Hampl didn't use, though she envied those children who did. Hampl concludes:

So what was I doing in this brief memoir? Is it simply an example of the curious relation a fiction writer has to the material of her own life? Maybe. But to tell the truth (if anyone still believes me capable of the truth), I wasn't writing fiction. I was writing memoir -- or was trying to. My desire was to be accurate. I wished to embody the myth of memoir: to write as an act of dutiful transcription. Yet clearly the work of writing a personal narrative caused me to do something very different from transcription. I am forced to admit that memory is not a warehouse of finished stories, not a gallery of framed pictures. I must admit that I invented.

Historians confront the problem all the time, especially in the "new social history", which seeks to go beyond the documentary record of great deeds and battles, and which often relies on oral history – which is to say, on memory. The historian David Thelen of Indiana University (and spouse of the psychologist Esther Thelen), has pointed out that "the challenge of history is to recover the past and introduce it to the present". This, of course, is the task of memory as well. Moreover, just as psychologists began their study of memory by focusing on issues of accuracy as in our measures of "percent correct" and "d-prime", historians have also been concerned with whether participants in some historical event accurately remember what actually occurred. As Thelen (1989, p. 1123) writes:

The historical study of memory would be the study of how families, larger gatherings of people, and formal organizations selected and interpreted identifying memories to sere changing needs. It would explore how people together search for common memories to meet present needs, how they first recognized such a memory and then agreed, disagreed, or negotiated over its meaning, and finally how they preserved and absorbed that meaning into their ongoing concerns .

More recently, under the influence of the reconstructive principle, psychologists have shifted their concern to the problem of how people remember. And along the same lines, the new generation of social historians are interested in "why historical actors constructed their memories in a particular way at a particular time". These parallels between cognitive psychology and history are the subject of a new scholarly journal, History and Memory -- which, although primarily concerned with the Nazi Holocaust, stands for a broader connection between history and psychology..

The problem with oral history is that sometimes it is wrong, as we saw in the "John Dean" problem. Listeners of a certain age will remember the White House counsel during the Nixon Administration, who at the Senate Watergate hearings gave detailed accounts of conversations he had in the Oval Office. It seemed as if Dean had a verbatim memory for the conversations, which made him an extremely persuasive witness. But after his testimony, Alexander Butterfield, another White House aide, revealed the existence of a White House taping system. Dick Neisser compared Dean's testimony to actual transcripts of two critical conversations. In the September 15, 1972 conversation, Nixon said none of the things attributed to him by Dan. Dean's memory of the March 21, 1973 "cancer on the Presidency" conversation, fairly represents the first hour of the meeting, when Dean was delivering a formal report, but not the second hour, which consisted of spontaneous conversation.

Neisser concludes: "Dean believes that he is recalling one conversation at a time, that his memory is "episodic" in Tulving's sense, but he is mistaken." Dean clearly believes his own testimony, largely because his specific memories are consistent with what he knows to be true on other grounds, and we are disposed to believe him for the same reasons. Mostly, however, he has remembered only the gist of his conversations with Nixon, abstracted over many such conversations, but he has imported many details into his memory, so that his memories are not faithful representations of any particular episodes.

More recently, we may have seen this kind phenomenon in the debate over recovered memories of trauma (Kihlstrom, 1996, 1997, 1998). In a typical recovered memory case, a person enters psychotherapy to cope with some kind of distress -- anxiety, depression, eating disorder, substance abuse, and the like. Some psychotherapists attribute these symptoms to the effects of trauma, especially incest and other forms of child sexual abuse, and many of their patients have in fact been traumatized; but other patients have no memory of such experiences. Many trauma therapists believe that traumatized individuals defensively invoke processes such as repression or dissociation, which in turn result in amnesia for the traumatic events. This amnesia affects only explicit memory; implicit memories of the trauma are spared, and emerge in the form of various kinds of symptoms. One goal of trauma therapy is to recover these critical memories, bringing them into consciousness so that they can be worked through.

Sometimes this process occurs spontaneously. On other occasions, the patient is encouraged to engage in what is known as "memory work" -- a set of techniques, including guided imagery, dream interpretation, journaling, bibliotherapy, and group reminiscence, which are intended to stimulate the recovery of forgotten memories. In either case, when memories of trauma do emerge, this is taken as evidence that the initial inference was correct, and that the patient's symptoms are part of the aftermath of trauma.

The techniques of memory work are not bad in principle -- in fact, many of them represent applications of the "seven principles" I described earlier in this talk, such as cue-dependency, encoding specificity, and schematic processing. However, these same techniques can promote distortions of memory, leading people to remember things that might not have happened to them.

In fact, as Katie Shobe and I have pointed out, the techniques of memory work effectively create the conditions for what Gisli Gudjonsson (e.g., Gudjonsson & Clark, 1986) has called "interrogative suggestibility" (Shobe & Kihlstrom, 2001). These include a closed social interaction consisting of just the patient, therapist, and like-minded supporters; therapeutic premises that, however plausible, may be ill-founded or uninformed; a relationship based on interpersonal trust, which forms a catalyst for leading questions to be interpreted as plausible or believable; uncertainty on the part of the patient about what happened in the past; a suggestive stimulus, including leading questions about trauma; a professional relationship, with at least the veneer of science, which allows such questions to be perceived as appropriate; and the shared belief that the techniques being employed will succeed in recovering valid memories of the past.

The problem is that recovered memories of trauma are rarely subject to independent corroboration, and it may very well be that recovered memories are misleading or false. This possibility has generally been dismissed by the recovered-memory movement, which considers the trauma-memory argument to be valid (even though there is very little evidence in favor of it). The problem is compounded by a therapeutic stance of unconditional positive regard, in which the therapist believes that it is inappropriate to question the patient's memories. As E. Sue Blume (1994) put it:

I'm not a detective; I'm a psychotherapist. It would be inappropriate for me to act like a detective. I'm there to help my client heal.

Judith Lewis Herman (1995), another prominent authority on trauma therapy, evidently agrees:

As a therapist, your job is not to be a detective; your job is not to be a fact finder.

Of course, we have known since Carl Rogers that an effective therapist needs to be supportive of the patient, but this support need not be, and probably should not be, uncritical. If a patient's current problems are to be attributed to historical events, as when depression or eating disorder are attributed to child sexual abuse, then it would seem to be incumbent on the therapist to corroborate the patient's story (or, for that matter, the therapist's own theory). Otherwise, therapist and patient risk engaging in a folie a deux, and treatment will be diverted from the patient's real problems. Note that I am not saying that trauma doesn't cause amnesia and other symptoms, or that recovered memories of trauma aren't valid. I'm only saying that the memories in question concern matters of historical fact, and we cannot assume that they are valid on their face.

Interestingly, there is now some evidence

that patients with PTSD may be more vulnerable to the

associative memory illusion. Susan Clancy and her colleagues

have recently reported that women who reported recovered

memories of childhood sexual abuse showed greater levels of

false recognition than women who always had such memories.

Douglas Bremner, Katie Shobe, and I found something similar in a

comparison of women with self-reported histories of childhood

sexual abuse. Those women who also carried a diagnosis of

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) showed significantly

higher levels of false recognition than those who did not, who

in turn were no more vulnerable to false recognition than

control women with neither PTSD nor a self-reported abuse

history (or, for that matter, control men). Nobody is claiming

that these self-reports of abuse are illusory, but the finding

does reinforce the point that self-reports need to be

corroborated wherever possible.

Interestingly, there is now some evidence

that patients with PTSD may be more vulnerable to the

associative memory illusion. Susan Clancy and her colleagues

have recently reported that women who reported recovered

memories of childhood sexual abuse showed greater levels of

false recognition than women who always had such memories.

Douglas Bremner, Katie Shobe, and I found something similar in a

comparison of women with self-reported histories of childhood

sexual abuse. Those women who also carried a diagnosis of

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) showed significantly

higher levels of false recognition than those who did not, who

in turn were no more vulnerable to false recognition than

control women with neither PTSD nor a self-reported abuse

history (or, for that matter, control men). Nobody is claiming

that these self-reports of abuse are illusory, but the finding

does reinforce the point that self-reports need to be

corroborated wherever possible.

These problems in psychotherapy are matched by problems in history, especially when historians rely on memoir or oral history, in the absence of written records or other forms of corroboration.

Consider the case of Binjamin Wilkomirski,

a Swiss musician whose book, Fragments (1995), portrays

a young Jewish child's life in the concentration camps during

the Holocaust. As Wilkomirski tells his story, he was born in

Latvia in 1939, witnessed his father's execution when he was 3

or 4 years of age, and was incarcerated in a series of camps. At

the end of the war, he was found wandering around Auschwitz, and

he was placed in an orphanage in Cracow.

Consider the case of Binjamin Wilkomirski,

a Swiss musician whose book, Fragments (1995), portrays

a young Jewish child's life in the concentration camps during

the Holocaust. As Wilkomirski tells his story, he was born in

Latvia in 1939, witnessed his father's execution when he was 3

or 4 years of age, and was incarcerated in a series of camps. At

the end of the war, he was found wandering around Auschwitz, and

he was placed in an orphanage in Cracow.

Wilkomirski included in his book a group

photo taken in a Polish orphanage around 1946: one of the

children is highlighted by the annotation, "Could this be me?".

In any event, he was relocated to Switzerland in 1948, and

recovered memories of his camp experiences during psychotherapy.

Wilkomirski's book is vivid and powerful. Jonathan Kozol,

reviewing it in the Nation, compared it with Elie

Wiesel's Night, one of a true classics of Holocaust

literature. The book won a host of literary prizes, including

the Jewish Quarterly prize for non-fiction and the

National Jewish Book Award for autobiography; the American

edition was listed by the New York Times as a "notable

book" for 1997. It has been called the "most successful Swiss

book since Heidi".

Wilkomirski included in his book a group

photo taken in a Polish orphanage around 1946: one of the

children is highlighted by the annotation, "Could this be me?".

In any event, he was relocated to Switzerland in 1948, and

recovered memories of his camp experiences during psychotherapy.

Wilkomirski's book is vivid and powerful. Jonathan Kozol,

reviewing it in the Nation, compared it with Elie

Wiesel's Night, one of a true classics of Holocaust

literature. The book won a host of literary prizes, including

the Jewish Quarterly prize for non-fiction and the

National Jewish Book Award for autobiography; the American

edition was listed by the New York Times as a "notable

book" for 1997. It has been called the "most successful Swiss

book since Heidi".

Fragments is also often cited as an example of the qualities of traumatic memory: it is fragmentary (hence its title), lacking in narrative coherence. Wilkomirski's story has also been touted as evidence for the success of recovered memory therapy. More recently, however, strong doubts have been raised about its provenance. In contrast to Night, it is lacking in specific details -- but then again, what do we expect from the memories of a 4-year-old child? More unsettling is the fact that few young children survived the camps. Children younger than 7 years were usually killed quickly after their arrival and apparently there were no children at all at Auschwitz.

Despite Wilkomirski’s photograph from

Crakow, Swiss adoption records indicate that Wilkomirski was

born Bruno Grossjean near Bern, Switzerland in 1941, to a poor,

unmarried, Protestant woman. He was a public ward until 1945,

when he was taken in as a foster child by Kurt and Martha

Dossekker, and raised by them in Zurich; in 1957, he was

formally adopted. Bruner appears in Dossekker family pictures

dating from 1946, and school records dating from 1947. He

attended university, worked as a musician and instrument-maker,

became an amateur historian of the Holocaust, and changed his

name to Binjamin Wilkomirski in the 1980s. Both his adoptive

parents died in 1986.

Despite Wilkomirski’s photograph from

Crakow, Swiss adoption records indicate that Wilkomirski was

born Bruno Grossjean near Bern, Switzerland in 1941, to a poor,

unmarried, Protestant woman. He was a public ward until 1945,

when he was taken in as a foster child by Kurt and Martha

Dossekker, and raised by them in Zurich; in 1957, he was

formally adopted. Bruner appears in Dossekker family pictures

dating from 1946, and school records dating from 1947. He

attended university, worked as a musician and instrument-maker,

became an amateur historian of the Holocaust, and changed his

name to Binjamin Wilkomirski in the 1980s. Both his adoptive

parents died in 1986.

It is now widely believed that Fragments is a work of "nonfiction fiction". It has become very common for writers to incorporate fictional scenes into nonfiction -- think of Truman Capote's In Cold Blood, or the work of Norman Mailer and Tom Wolfe. Just last year, Edmund Morris inserted himself, like Woody Allen’s Zelig, as a character in his authorized biography of Ronald Reagan, following the president from a high-school football field in Dixon, Illinois, straight into the White House. Wilkomirski seems to have done the opposite: to incorporate nonfiction, details of the Holocaust gleaned from a lifetime's obsessive reading, into fiction -- a memoir which isn't based on personal recollection. The irony is that Fragments works as a piece of fiction -- but as one critic noted, "Nonfiction sells better than fiction".

Moreover, in a striking parallel to the views of some trauma therapists, some publishers seem to feel that it is not their job to fact-check their authors' memoirs. Arthur Samuelson, Wilkomirski's American publisher, noted that:

We don't have fact checkers. We are not a detective agency. We are a vehicle for authors to convey their work, and we distribute their information with a feeling of responsibility.

Similarly, Elizabeth Janeway, his American editor, stated that:

We don't vet books on an adversarial basis. We have no means of independent collaboration [sic].

Reliance on uncorroborated memory may be good for the publishing business, but it may not be good for history. But then again, it may not be good for the publishing business, either. After commissioning an independent investigation, Wilkomirski's German publisher withdrew the book from circulation.FN

In an article on "witness literature", Timothy Garton Ash referred to Wilkomirski as an example of a writer on "the frontier between the literature of fact and the literature of fiction", but whose book lacks the essential "truth test" of "veracity" (On the Frontier", New York Review of Books, 11/07/02).

Reading Fragments now, one is amazed that it could ever have been hailed as it was. The wooden irony ("Majdanek is no playground"), the hackneyed images (silences broken by the sound of cracking skulls), the crude, hectoring melodrama (his father squashed against the wall by a transporter, dead women with rats crawling on their stomachs). Material which, once you know it is fraudulent, is truly obscene. But even before one knew that, all the aesthetic alarms should have sounded. For every page has the authentic ring of falsehood.

In an interesting twist on the Wilkomirski story, a novel about the Holocaust, written in the first person, has been reissued as a memoir -- because that's what it actually is ("Holocaust Memoir is Reissued, No Longer Designated Fiction" By Ralph Blumenthal, New York Times 7/12/02). Jakob Littner's Notes from a Hole in the Ground by Wolfgang Koeppen (1992), was originally published, in 1948, as Notes from a Hole in the Ground by Jakob Littner, a Hungarian-born Polish Jew who was a stamp dealer in Munich before the war. Koeppen served as editor of the book. Littner died in 1950.

Koeppen himself emerged as a prominent German writer in the 1950s. In 1992, Judischen Verlag issued Notes under its revised title with Koeppen listed as author and the book categorized as "fiction". When Littner's surviving relatives protested the appropriation, Judischen Verlag (interestingly, a subdivision of Suhrkamp Verlag, which also published Wilkomirski's "memoir") replied that Koeppen had "given the notes an adequate form" and acknowledged Littner in the title. But the situation is more complicated than that. Reinhard Zachau, a scholar of German literature, discovered that Koeppen had changed Littner's text in important ways. More important in the context of memory, Koeppen seems to have made Littner's story his own. Commenting on "his" book, Koeppen wrote, "I ate American rations and wrote the story about the suffering of a German Jew. In so doing it became my story". Koeppen died in 1996. Littner's book has now been reissued under his original title, Journey Through the Night (Continuum, 2000), categorized as "nonfiction".

Questions of fact have also been raised

about another autobiography, I, Rigoberta Menchu: An Indian

Woman in Guatemala (1983), which chronicles the life of a

Maya Indian growing up in during a period of civil war which

pitted a right-wing government against left-wing guerillas, and

landowners of European descent against indigenous peasants.

Menchu details the squalid conditions of peasant existence, such

as her lack of formal education and her youngest brothers'

deaths from malnutrition. She also related personal horrors,

such as an army attack on her village, the burning of prisoners

in the central plaza, the torture and killing of her mother and

brother, the police execution of her father.

Questions of fact have also been raised

about another autobiography, I, Rigoberta Menchu: An Indian

Woman in Guatemala (1983), which chronicles the life of a

Maya Indian growing up in during a period of civil war which

pitted a right-wing government against left-wing guerillas, and

landowners of European descent against indigenous peasants.

Menchu details the squalid conditions of peasant existence, such

as her lack of formal education and her youngest brothers'

deaths from malnutrition. She also related personal horrors,

such as an army attack on her village, the burning of prisoners

in the central plaza, the torture and killing of her mother and

brother, the police execution of her father.

I, Rigoberta Menchu is a very powerful book, which quickly entered the canon of Latin American Literature; it is one of the most popular books sold on college campuses, and won Menchu the Nobel Peace Prize in 1992. There is no doubt that the conditions of the time in Guatemala were awful, mostly by virtue of government atrocities perpetrated in behalf of the oligarchy. At the same time, research by David Stoll (1999), an anthropologist at Middlebury College, has revealed that many of the specific incidents in Menchu's book were exaggerated or fabricated. Menchu received a junior high-school education as a scholarship student at an elite Catholic boarding school; she almost certainly never worked on a plantation; her father was killed in a land dispute with his in-laws; her brother was killed by the army, but she never saw it happen, and he was not burned in the plaza; her youngest brother is alive and well; two older brothers died of starvation and disease, but before Menchu was born. Stoll concludes that Menchu's book cannot be strictly autobiographical, because she simply did not have many of the experiences that she claimed to witness.FN

But it would be too simple, and wrong, to say that Dean, and Wilkomirski, and Menchu lied, and it would be too simple to say that patients with false or implausible recovered memories lie. There may be a lot of truth in their accounts -- just not historical truth. After all, in the immortal words of Garry Trudeau's Doonesbury, Richard Nixon was "Guilty, guilty, guilty!", and John Dean got that right. Apparently, Wilkomirski believes that his story is true: according to the New York Times, when the veracity of his book was challenged by his German publisher, he stood up defiantly and declared:

I am Binjamin Wilkomirski!.

Even his severest critics think that he is sincere. Menchu, for her part, replied that her story is "my truth", and that:

I have a right to my own memories

-- though more recently she has conceded that some material was historically false.

Errors and distortions are natural

consequences of the reconstructive process: individual

experiences will be confused, vicarious experiences will be

remembered as personal, and the stories of many individuals will

be conflated into the story of one person. Ronald Reagan

sometimes told about being among the troops who liberated the

Nazi death camps at the end of World War II, when in fact he was

in Hollywood watching documentary film footage of their

liberation as a member of the First Motion Picture Unit of the

U.S. Army. (The film was subsequently collected into the

documentary, Lest We Forget, which Reagan showed to both

his sons on their 14th birthdays.)

Errors and distortions are natural

consequences of the reconstructive process: individual

experiences will be confused, vicarious experiences will be

remembered as personal, and the stories of many individuals will

be conflated into the story of one person. Ronald Reagan

sometimes told about being among the troops who liberated the

Nazi death camps at the end of World War II, when in fact he was

in Hollywood watching documentary film footage of their

liberation as a member of the First Motion Picture Unit of the

U.S. Army. (The film was subsequently collected into the

documentary, Lest We Forget, which Reagan showed to both

his sons on their 14th birthdays.)

Michael Korda, who edited Reagan’s autobiography, tells of the President bringing an audience of Medal of Honor winners to tears with the story of a bomber pilot, whose plane was shot down during a raid, ordering his crew to bail out. Just as he is about to do so himself, he finds that his tail-gunner, a fresh-eyed kid, is trapped and can't escape. The pilot grasps the boy’s hand and says, "Don't worry, son, we'll ride down together". Nobody bothered to ask how anyone ever found out about this episode -- and in fact it’s the climax of A Wing and a Prayer (1944), one of the most successful propaganda films of World War II (not least because of its effective combination of documentary footage with scenes filmed on a sound stage).

Remember the line from American Beauty? "I know video is a poor excuse, but it helps me remember." Maybe memory is just like a movie after all. These incidents remind us that memories are not just representations stored in the mind and the brain; memories are also things we do, in the process of reconstructing the past. As such, memories serve personal and social purposes.

On the personal side, our memories appear to be reconstructed in accordance with theories of the self: our views of who we are and how we got that way. Each autobiographical memory, then, is part of a personal narrative, which reflects our views of ourselves. Long ago, Alfred Adler (1937) made this point about our earliest recollections: that they represent the current "life style" of the individual, and serve to remind the person of who he or she is. Adler thus reverses the Freudian view of causation: childhood memories don't determine adult personality; rather adult personality determines what will be remembered from childhood. More recently, Michael Ross (1989, 1994) has argued that people construct their personal histories around tacit theories of the self, and revise these histories as our self-concepts change.

One function of the past is to explain the present. We see this clearly in the search for recovered memories of trauma, as the psychoanalyst Brooks Brenneis, himself a severe critic of the recovered memory movement, has pointed out. But we also see it elsewhere. Wilkomirski's and Menchu's memoirs reflect a personal truth, a personal history remembered from a particular point of view. They are subjectively compelling -- even if they are inaccurate or false outright.

But more than that, memories serve social purposes. Menchu says that her book represents her truth, but she also says that 'It's also the testimony of my people", and that her autobiography is "part of the historical memory and patrimony of Guatemala". This is the meaning of Stoll's subtitle: in some sense, Menchu's story is indeed "the story of all poor Guatemalans". Thus, individual memories are also constructed around tacit theories of society: personal narratives are part of social narratives, and vice-versa.

So-called flashbulb memories, once attributed to a "Now Print!" mechanism in the brain, reflect this relationship between the personal and the social, the individual and the collective. Flashbulb memories may or may not be accurate, but as Dick Neisser (1981) has pointed out, they are benchmarks lying at the intersection of private and public history:

They are the places where we line up our own lives with the course of history itself and say "I was there".

This perspective is consistent with Bartlett's insight about memory, as reflected in the full title of his 1932 book: Remembering: A Study in Experimental and Social Psychology. In the latter part of the book, the part hardly ever read by psychologists, Bartlett wrote that:

Social organization gives a persistent framework into which all detailed recall must fit, and it very powerfully influences both the manner and the matter of recall.

I think this point as reflected in yet another principle of memory, the Interpersonal Principle:

Remembering is an act of communication, of information sharing and self-expression, as well as an act of information retrieval. Accordingly, our memories of the past are shaped by the interpersonal context in which they are encoded, stored, and retrieved.

Psychologists don't study the social aspects of memory much, but historians and sociologists have recently taken up the problem. Maurice Halbwachs (1877-1945), who was a student of both the psychologist Bergson and the sociologist Durkheim, drew our attention to collective memories shared within groups and institutions. In fact, he argued that because "We are never alone", all individual memories are collective -- the only exception being memory for dreams. As Halbwachs (1925) argued:

The individual calls recollections to mind by relying on the frameworks of social memory….. There are surely many facts, and many details…, that the individual would forget if others did not keep their memory alive for him. But, on the other hand, society can live only if there is sufficient unity of outlooks among the individuals and groups comprising it…. This is why society tends to erase from its memory all that might separate individuals, or that might distance groups from each other. It is also why society, in each period, rearranges its recollections in such a way as to adjust them to the variable conditions of its equilibrium.

As an example of "the social frameworks of memory", Halbwachs pointed to "the collective memory of the family": that there are events shared only by family members, and events known only to family members. I do not know of good data on this subject, but intuitively it seems clear that families are bound together by their shared memories at least as much as they are bound together by their shared genes. When you enter a family, to the extent that you enter a family, you acquire its memories; and when you leave a family, to the extent that you leave it, you begin to forget. Memories probably play a critical role in other natural groups as well.

More recently, Halbwachs’ views have been championed by a new generation of cognitive sociologists, who view memory as a social construction, the past as shaped by the concerns of the present. Eviatar Zerubavel, in his recent book Social Mindscapes (1997), offers the sociology of knowledge as an antidote to the universalism and particularism of psychology: as experimentalists, acting nomothetically, we are interested in how humans in general remember; and as clinicians, acting idiographically, we are interested in how and what individuals remember. But Zerubavel points out that

There are no mnemonic Robinson Crusoes.

In his view, individual remembering does not take place in a social vacuum; that others help us to remember, and to forget; and that there are social rules of remembering, which determine what we are to remember, and what we are to forget. Through a process of mnemonic socialization, we acquire new memories when we enter social environments; our communities are communities of thought, comprising a fund of social knowledge and a body of social memory. As members of mnemonic communities, we remember things we never experienced, and come to identify, as group members, with a collective past.

Zerubavel points out that many social conflicts are best viewed as "mnemonic battles" over what is to be remembered, and how. We see this clearly in the literature of the Holocaust, which is dominated by the theme of memory, and the injunction never to forget. We also see a struggle over memory in the controversies that surround certain museum exhibitions, such as Harlem on My Mind, The West as America, and the Smithsonian’s aborted attempt to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II (Dubin, 1999).

In other words, memory is simultaneously a

biological fact, a faculty of mind, an exercise in rhetoric, and

a social construction. The clear implication of this conclusion

is that memory can no longer be studied by cognitive

psychologists alone, let alone by cognitive neuroscientists.

Within psychology, cognitive psychologists need to ally

themselves with personality and social psychologists, who have

expertise in such areas as persuasive communication, identity

formation and the self-concept, causal attribution, and

impression management. But memory can't be studied by

psychologists alone, either. We need to understand the social

purposes that memories serve, and the impact of social

structures and organizations on what Bartlett called the "manner

and matter" of remembering. We also need to understand memory as

a form of rhetoric and literature, a mode of speaking and

writing about oneself and one's society.

In other words, memory is simultaneously a

biological fact, a faculty of mind, an exercise in rhetoric, and

a social construction. The clear implication of this conclusion

is that memory can no longer be studied by cognitive

psychologists alone, let alone by cognitive neuroscientists.

Within psychology, cognitive psychologists need to ally

themselves with personality and social psychologists, who have

expertise in such areas as persuasive communication, identity

formation and the self-concept, causal attribution, and

impression management. But memory can't be studied by

psychologists alone, either. We need to understand the social

purposes that memories serve, and the impact of social

structures and organizations on what Bartlett called the "manner

and matter" of remembering. We also need to understand memory as

a form of rhetoric and literature, a mode of speaking and

writing about oneself and one's society.

For almost a century since Ebbinghaus, most of the advances in our understanding of memory were made by behavioral analyses at the level of the individual subject, without reference to biology. Beginning with the study of H.M., and fostered by advances in brain imaging and in molecular and cellular biology, psychologists have begun to make progress in understanding the biological basis of memory. But psychology is in a unique position to connect the individual's mental states and processes both to what is going on in the brain and to what is going on in the world outside the individual mind. We have to do this, or we will fail our unique intellectual mission. We're doing a good job on the biological end, quickly moving past what former NIMH Director Steven Hyman has called the "false-color phrenology" of our earliest brain-imaging work. But we need to do a better job on the social end. We need to connect the study of memory (and indeed all of mind and behavior) up as well as down -- to the other social sciences, and to the humanities, as well as to the other biological sciences. Understanding memory requires going beyond the study of the individual. This is a project in which all the social sciences can take part, and the humanities as well, but this will only happen if psychologists don't claim memory as our exclusive territory.

Distinguished Lecture presented at the annual meeting of the Rocky Mountain Psychological Association, Tucson, April 2000. An earlier version was presented in 1999 at Washington University, St. Louis, under the auspices of the Luce Professorship in Individual and Collective Memory, at the invitation of . A shorter version will appear in the Fall 2002 issue of Proteus: A Journal of Ideas, as part of a special issue on memory.

I thank H.L. Roediger and James Wertsch for the invitation to speak at Washington University; Elizabeth Glisky for the invitation to present at RMPA; and Jennifer Beer, Marilyn Dabady, Jennifer Dorfman, Martha Glisky, Lucy Canter Kihlstrom, Michael Kim, Susan McGovern, Lillian Park, and Katharine Shobe for collaborations and conversations contributing to the positions taken here.

The point of view presented in this paper is based on research supported in part by Grant #MH-35856 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

This is a work in progress. Proper reference citations will be added as time permits; in the meantime, they are available from the author.

A different story must be told about the novel in other languages. The very first novel, Murasaki's Tale of Genji, written in 11th-century Japan, is told in the third person, like a modern novel. Return to text.

A later literary invention, extremely interesting in the present context, is the unreliable narrator. Return to text.

FNBlume, interview with Morely Safer on 60 Minutes, CBS television, 04/17/94; Herman, interview with Ofra Bickel on Frontline, PBS, 1995. Return to text.

FNThe Wilkomirski story was first broken by Daniel Ganzfried in the Swiss newspaper Weltwoche (August 1998). Extended coverage in English includes articles by Gourevich (1999) and Lappin (1999), and books by Machler (2001) and Eskin (2002). Aside from these, my primary source of information on the Wilkomirski affair is a series of articles and columns in the New York Times:

|

"A Holocaust Memoir in Doubt: Swiss Records Contradict a Book on Childhood Horror" by Doreen Carvajal (11/3/98); |

|

|

"In Fact, It's Fiction" by Martin Arnold (11/12/98); |

|

|

"Disputed Holocaust Memoir Withdrawn" by Doreen Carvajal (10/14/99); |

|

|

"Publisher Drops Holocaust Book" (unsigned, 11/3/99) |

|

|

"Does Nonfiction Mean Factual?" by Martin Arnold (7/20/00). |

The case was also covered in a segment of 60 Minutes (CBS, 2/7/99), and in "The Survivor", an episode of the Investigative Reports series produced by Wolf Gebhardt on the A&E cable network (12/29/99). There were also programs on the Wilkomirski case produced in the United Kingdom on BBC1 "Child of the Death Camp -- Truth and Lies") and BBC2 ('Mistaken Identity"), both shown in 1999. Illustrations from from Wilkomirski's book and Lappin's Granta article. Return to text.

FNSee Stoll (1998) and Canby (1999). Aside from Canby's article, my primary source for information about the dispute over Menchu's recollections is a series of articles in the New York Times:

|

"Tarnished Laureate: Nobel Winner Finds Her story Challenged" by Larry Rohter (12/15/98); |

|

|

"Nobel Laureate Vows to Defend Her Book" by the Associated Press (12/18/98) ; |

|

|

"Guatemala Laureate Defends 'My Truth'" by Julia Preston (1/21/99); |

|

|

"Peace Prize Winner Admits Discrepancies" by the Associated Press (2/12/99). |

The dispute stimulated a large number of letters to the editor of the Times, as well as an editorial (12/17/98). Illustration from Stoll's book. Return to text.

Korda tells the story in his memoir (2000). Frances Fitzgerald, in Way Out There in the Blue: Reagan, Star Wars, and the End of the Cold War (2000) attributes the anecdote to a morale-boosting piece that appeared in the Reader's Digest for April 1944. The accompanying illustration is taken from Reagan's authorized biography (1999), in which the author, Edmund Morris, appears as a fictional character! Return to text.

Adler, A. (1937). The significance of early recollections. International Journal of Individual Psychology, 3, 283-287.

Anderson, J. R. (1976). Language, Memory, and Thought. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ansbacher, H. L. (1973). Adler's interpretation of early recollections: Historical account. Journal of Individual Psychology, 29, 135-145.

Atlas, J. (1996). confessing for voyeurs: The age of the literary memoir is now. New York Times Magazine(May 12).

Bartlett, F. C. (1932). Remembering: A study in experimental ad social psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bower, G. H. (1967). A multicomponent theory of the memory trace. In K. W. Spence & J. T. Spence (Eds.), The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 1, pp. 230-327). New York: Academic.

Canby, P. (1999). The truth about Rigoberta Menchu. New York Review of Books(April 9), 28ff.

Dubin, S. C. (1999). Displays of power: Memory and amnesia in the American museum. New York: New York University press.

Ebbinghaus, H. (1885/1964). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. New York: Dover.

Eskin, B. (2002). A life in pieces: The making and unmaking of Binjamin Wilkomirski. New York: Norton.

Gardiner, J. M. (1988). Functional aspects of recollective experience. Memory & Cognition, 16, 309-313.

Gourevitch, P. (1999, June 14). The memory thief. The New Yorker, 48-68.

Hampl, P. (Ed.). (1999). I could tell you stories: Sojourns in the land of memory. New York: Norton.

Hilts, P. J. (1995). Memory's ghost : the strange tale of Mr. M and the nature of memory. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Kihlstrom, J. F. (1996). The trauma-memory argument and recovered memory therapy, The recovered memory/false memory debate. (pp. 297-311). San Diego, CA, USA: Academic Press, Inc.

Kihlstrom, J. F. (1998). Exhumed memory, Truth in memory. (pp. 3-31). New York, NY, USA: The Guilford Press.

Kihlstrom, J.F. (1998, August). Interactions between implicit and explicit memory. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, San Francisco. (b) Full text available at: http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~kihlstrm/apa98b.html

Kihlstrom, J. F., & Barnhardt, T. M. (1993). The self-regulation of memory: For better and for worse, with and without hypnosis, Handbook of mental control. (pp. 88-125). Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Kihlstrom, J.F., Kim, M., & Dabady, M. (1996, November). Remembering, knowing, and feeling in episodic recognition. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Psychonomic Society, Chicago. Full text available at: http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~kihlstrm/psychn96.html

Kihlstrom, J.F., & Kim, M. (1998, November). Judgment time, learning, and recollective experience. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Psychonomic Society, Dallas. Full text available at: http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~kihlstrm/psychn98.html

Kim,. M., & Kihlstrom, J.F. (1997, November). Exposure, confidence, and recollective experience in episodic recognition. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Psychonomic Society, Philadelphia. Full text available at: http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~kihlstrm/psychn97.html

Korda, M. (1999). Another life : a memoir of other people ( 1st ed.). New York: Random House.

Lappin, E. (1999, Summer). The man with two heads. Granta, 7-66.

Lashley, K. S. (1950). In search of the engram. Symposia of the Society for Experimental Biology (Vol. 4, pp. 454-482). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Mächler, S., & Wilkomirski, B. (2001). The Wilkomirski affair: A study in biographical truth ( 1st ed ed.). New York: Schocken Books.

McAdams, D. P., Josselson, R., & Lieblich, A. (Eds.). (2001). Turns in the road: Narrative studies of lives in transition. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association.

McConkey, J. (Ed.). (1996). The anatomy of memory: An anthology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Menchú, R., & English. (1984). I, Rigoberta Menchú : an Indian woman in Guatemala. London: Verso.

Morris, E. (1999). Dutch: A memoir of Ronald Reagan ( 1st ed.). New York: Random House.

Neisser, U. (1981). John Dean's memory: A case study. Cognition, 9, 1-22.

Roediger, H. L. (1996). Memory illusions. Journal of Memory & Language, 35, 76-.