Types and Traits

How do you describe another person? How do you capture the gist of his or her personality, showing how the person is like some other people without obscuring his or her uniqueness? Make no mistake about it: We do describe other people, all the time, in the course of our everyday living. Psychologists, novelists and short-story writers, and the public at large are constantly engaged in describing other people, in trying to articulate to themselves, and communicate to someone else, what another person is like. This activity is certainly as old as human language, and the scientific study of personality properly begins with a consideration of how such descriptive systems evolved.

In some cultures, such as the island of Bali in the South Pacific, the Oriya in India, and the Gahuku-Gama of New Guinea, people are described in terms of lists of specific actions which they perform in particular situational contexts (Shweder & Bourne, 1981). In America, however, and in Western culture generally, we tend to describe each other either with nouns designating whole classes of people (such as "extravert", "genius", "hippie", "preppie"), or with an adjective describing some salient feature of our personalities (such as "friendly", "intelligent", "drugged", or "smug"). The situation is a little more complicated than this, because many adjectives have corresponding noun forms and vice-versa, but in general we tend to attach context-free descriptive labels to other people. This preference in ordinary language is parallel to the scientific descriptions of personality produced by Western personology. This scientific taxonomy, in turn, has its roots in certain literary. forms which center on the description of people. In order to understand how this transpired, we begin at the beginnings of Western science and literature: the Greeks.

Theophrastus and the Characterological Tradition in Literature

The chief preoccupation of Greek science was with classification. Aristotle (384-322 B.C.), in his Historia Animalium provided a taxonomy, or classificatory scheme, for biological phenomena.

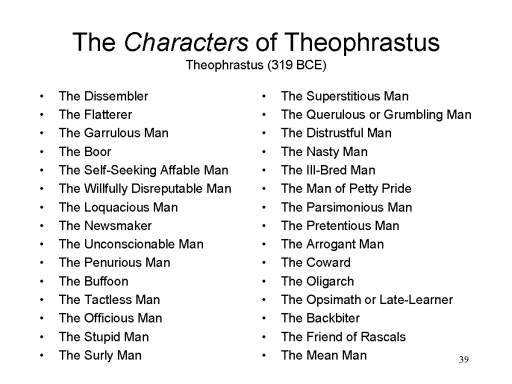

Theophrastus

(370-287 B.C.), his successor as head of the Peripatetic

School in Athens (so named because the teachers strolled

around the courtyard while lecturing), followed his example by

developing a taxonomy of people. His work is embodied in Characters,

a delightful book in which he described the various types of

people encountered in Athenian society. Unfortunately, that

portion of the book which described socially desirable types

has been lost to history: All that remains are his portraits

of 30 thoroughly negative characters, most of whom are

instantly recognizable even today, more than 2000 years later.

All his descriptions follow the same expository format: a

brief definition of the dominant feature of the personality

under consideration, followed by a list of typical behaviors

representative of that feature.

Theophrastus

(370-287 B.C.), his successor as head of the Peripatetic

School in Athens (so named because the teachers strolled

around the courtyard while lecturing), followed his example by

developing a taxonomy of people. His work is embodied in Characters,

a delightful book in which he described the various types of

people encountered in Athenian society. Unfortunately, that

portion of the book which described socially desirable types

has been lost to history: All that remains are his portraits

of 30 thoroughly negative characters, most of whom are

instantly recognizable even today, more than 2000 years later.

All his descriptions follow the same expository format: a

brief definition of the dominant feature of the personality

under consideration, followed by a list of typical behaviors

representative of that feature.

The Distrustful Man.It goes without saying that Distrustfulness is a presumption of dishonesty against all mankind; and the Distrustful man is he that will send one servant off to market and then another to learn what price he paid; and will carry his own money and sit down every furlong to count it over. When he is abed he will ask his wife if the coffer be locked and the cupboard sealed and the house-door bolted, and for all she may say Yes, he will himself rise naked and bare-foot from the blankets and light the candle and run round the house to see, and even so will hardly go to sleep. Those that owe him money find him demand the usury before witnesses, so that they shall never by any means deny that he has asked it. His cloak is put out to wash not where it will be fulled best, but where the fuller gives him good security. And when a neighbor comes a-borrowing drinking-cups he will refuse him if he can; should he perchance be a great friend or a kinsman, he will lend them, yet almost weigh them and assay them, if not take security for them, before he does so. When his servant attends him he is bidden go before and not behind, so that he may make sure he do not take himself off by the way. And to any man who has bought of him and says, 'Reckon it up and set it down; I cannot send for the money just yet,' he replies, 'Never mind; I will accompany you home' (Theophrastus, 319 B.C./1929, pp. 85-87).

Theophrastus initiated a literary tradition which became very popular during the 16th and 17th centuries, especially in England and France (for reviews see Aldington, 1925; Roback, 1928). However, these later examples represent significant departures from their forerunner. Theophrastus was interested in the objective description of broad types of people defined by some salient psychological characteristic. In contrast, the later efforts show an increasing interest in types defined by social class or occupational status. In other instances, the author presents word portraits of particular. individuals, with little apparent concern with whether the subjects of the sketch are representative of any broader class at all. Early examples of this tendency are to be found in the descriptions of the pilgrims in Chaucer's (c. 1387) Canterbury Tales. Two examples that lie closer to Theophrastus' intentions are the Microcosmographie of John Earle (1628) and La Bruyere's Les Caracteres (1688). More recent examples of the form may be found in George Eliot's Impressions of Theophrastus Such (1879) and Earwitness: Fifty Characters (1982) by Elias Canetti, winner of the 1981 Nobel Prize for Literature.

The later character sketches also became increasingly opinionated in nature, including the author's personal evaluations of the class or individual, or serving as vehicles for making ethical or moral points. Like Theophrastus, however, all of these authors attempted highly abstract character portraits, in which individuals were lifted out of the social and temporal context in which their lives ran their course. Reading one of these sketches we have little or no idea what forces impinged on these individuals to shape their thoughts and actions; what their motives, goals, and intentions were; or what their lives were like from day to day, year to year. As authors became more and more interested in such matters they began to write "histories" or "biographies" of fictitious characters -- in short, novels. In the 18th century the novel quickly rose to a position as the dominant literary form in Europe, and interest in the character-sketch waned. Character portraits still occur in novels and short stories, but only as a minor part of the whole -- perhaps contributing to the backdrop against which the action of the plot takes place. Again, insofar as they describe particular individuals, character sketches imbedded in novels lack the quality of universality which Theophrastus sought to achieve.

Scientific and Pseudoscientific Typologies in the Ancient World

Characters is a classic of literature because -- despite the radical differences between ancient Athenian culture and our own -- Theophrastus' 30 character types are instantly recognizable by readers of any place and time. As a scientific endeavor, however, it is not so satisfying. In the first place, Theophrastus provides no evidence in support of his typological distinctions: were there really 30 negative types of Greeks, or were there 28 or 32; and if there were indeed 30 such types, were they these 30? Moreover, Theophrastus did not offer any scheme to organize these types, showing how they might be related to each other. Perhaps more important -- assuming that Characters attained classic status precisely because Theophrastus' types were deemed to be universal -- is the question of the origin of the types. Theophrastus raised this question at the very beginning of his book, but he did not offer any answer:

I have often marvelled, when I have given the matter my attention, and it may be I shall never cease to marvel, why it has come about that, albeit the whole of Greece lies in the same clime and all Greeks have a like upbringing, we have not the same constitution of character (319 B.C./1929, p. 37).

The ancients had solutions to all problems, both scientific and pseudoscientific.

Astrology

Some popular approaches to creating typologies of personality have their origins in ancient folklore, and from time to time they have been endowed with the appearance of science. For example, a tradition of physiognomy diagnosed personality on the basis of similarities in physical appearance between individual humans and. species of infrahuman animals. Thus, a person possessing hawk-like eyes, or an eagle-like nose was presumed to share behavioral characteristics with that species as well.

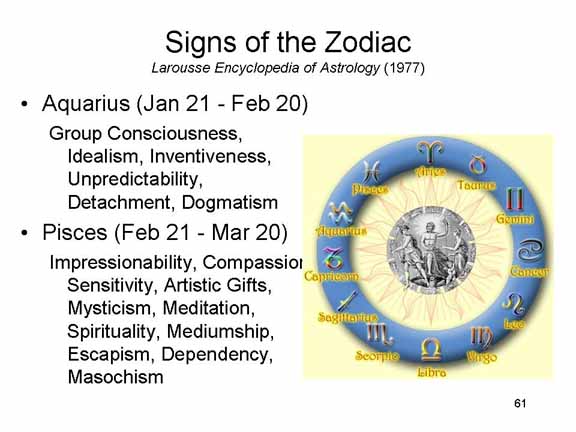

By far the most prominent of these pseudoscientific approaches to personality was (and still is) astrology, which holds that the sun, moon, planets, and stars somehow influence. events on earth. The theory has its origins in the ancient idea that events in the heavens -- eclipses, conjunctions of stars, and the like -- were omens of things to come. This interest in astral omens has been traced back almost 4000 years. to the First Dynasty of the kingdom of Babylon. Astrology per se appears to have begun in the 3rd century B.C., when religious authorities began using the planets to predict events in an individual's life. The various planets, and signs of the Zodiac, were thought to be associated with various attributes. The astrologer prepared a horoscope, or map of the heavens at the moment of an individual's birth (or, sometimes, his or her conception), and predicted on the basis of the relative positions of the heavenly bodies what characteristics the person would possess. Of course, because these relative positions varied constantly, somewhat different predictions could be derived for each individual. To the extent that two individuals were born at the same time and in the same place, then, they would be similar in personality.

-

Aries is essentially a sign of beginnings, of boundless creativity and pure energy. Arians ... must be up and doing for the sheer joy of it, especially if the activity involves adventure, the exploration of unknown territory, and even danger. The rulership of Mars bestows strength and courage, and a strong desire nature, which means both sexual desire and the drive to conquer and possess material things, power, and fame. The incredible Aries energy in initiating new projects is a blend of the enthusiasm and self-confidence of fire and the outgoing activity of cardinality. The polar opposite of indecisive Libra, Arians seldom have time to look before they leap; they simply rush forward headlong, for it is their business to lead and inspire.

-

The symbol for Scorpio is the scorpion, a creature that travels by night and is feared for its deadly sting. Though all Scorpio people are by no means venomous and cruel, the symbol conveys the qualities of secretiveness, penetration, and power that do characterize the natives of this sign .... Besides the strong sexuality for which they are famous, Scorpio people also have an awareness of death that is often not fearful .... Indeed, if they are afraid of anything at all, it is of being known as deeply as they wish to know. Their ability to penetrate and probe may be channeled constructively into research or healing or it may be used to manipulate people in personal relationships.

Astrology was immensely powerful in the ancient world, and even in this century various political leaders such as Adolph Hitler in Germany and Lon Nol in Cambodia have computed horoscopes to help them in decision-making. However, by the 17th century astrology had lost its theoretical underpinnings. First, the new astronomy of Copernicus (1473-1543), Galileo (1564-1642), and Kepler (1571-1630), showed that the earth was not at the center of the universe, as astrological doctrine required. Then, the new physics of Descartes (1596-1650) and Newton (1642-1727) proved that the stars could have no physical influence on the earth. If that were not enough, the more recent discovery of Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto would have created enormous problems for a system that was predicated on the assumption that there were six, not nine, planets. In any event, there is no credible evidence of any lawful relationship between horoscope and personality.

And even if it were, it wouldn't be a matter of the position of the planets causing individual differences in personality. More likely, any such effect would be mediated by what Robert K. Merton (1949) called a self-fulfilling prophecy. That is, people who believe that Scorpios are secretive may treat such individuals in a way that makes them secretive.

The Humour Theory of Temperament

Greek science had another answer for these questions, in the form of a theory first proposed by Hippocrates (460?-377? B.C.), usually acknowledged as the founder of Western medicine, and Galen (130-200? A.D.), a Roman physician who was his intellectual heir. Greek physics asserted that the universe was composed of four cosmic elements: air, earth, fire, and water. Human beings, as microcosms of nature, were composed of four corresponding humors -- biological substances which paralleled the cosmic elements. The predominance of one humor over the others endowed each individual with a particular type of temperament.

The cosmic elements, their corresponding humors, and the resulting temperamental types are given in the following table:

Cosmic Element |

Bodily Humour |

Temperament |

Air |

Blood |

Sanguine |

Earth |

Black Bile |

Melancholic |

Fire |

Yellow Bile |

Choleric |

Water |

Phlegm |

Phlegmatic |

Humor theory was the first scientific theory of personality -- the first to base its descriptions on some basis other than the personal predilections of the observer, and the first to provide a rational explanation of individual differences. The theory was extremely powerful, and dominated both philosophical and medical discussions of personality well into the 19th century.

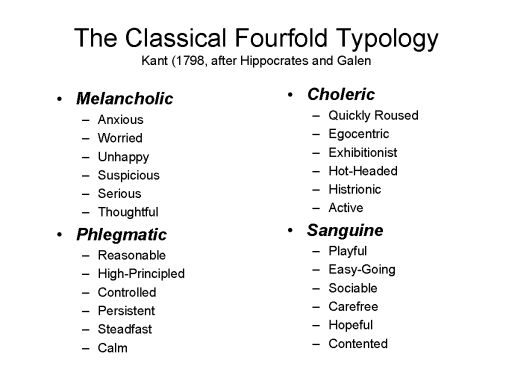

Immanuel Kant, the German philosopher, abandoned Greek humor

theory but retained its fourfold classification of personality

types in his Anthropology (1798). His descriptions of

the four personality types have a flavor strongly reminiscent

of Theophrastus'Characters.

Immanuel Kant, the German philosopher, abandoned Greek humor

theory but retained its fourfold classification of personality

types in his Anthropology (1798). His descriptions of

the four personality types have a flavor strongly reminiscent

of Theophrastus'Characters.

-

The Sanguine Temperament. The sanguine person is carefree and full of hope; attributes great importance to whatever he may be dealing with at the moment, but may have forgotten all about it the next. He means to keep his promises but fails to do so because he never considered deeply enough beforehand whether he would be able to keep them. He is good-natured enough to help others, but is a bad debtor and constantly asks for time to pay. He is very sociable, given to pranks, contented, doesn't take anything very seriously and has many, many friends. He is not vicious, but difficult to convert from his sins; he may repent, but contrition (which never becomes a feeling of guilt) is soon forgotten. He is easily fatigued and bored by work, but is constantly engaged in mere games -- these carry with them constant change, and persistence is not his forte.

-

The Melancholic Temperament. People tending toward melancholia attribute great importance to everything that concerns them. They discover everywhere cause for anxiety, and notice first of all the difficulties in a situation, in contradistinction to the sanguine person. They do not make promises easily, because they insist on keeping their word, and have to consider whether they will be able to do so. Al this is so not because of moral considerations, but because interaction with others makes them worried, suspicious, and thoughtful; it is for this reason that happiness escapes them.

-

The Choleric Temperament. He is said to be hot-headed, is quickly roused, but easily calmed down if his opponent gives in; he is annoyed without lasting hatred. Activity is quick, but not persistent. He is busy, but does not like to be in business, precisely because he is not persistent; he prefers to give orders, but does not want to be bothered with carrying them out. He loves open recognition, and wants to be publicly praised. He loves appearances, pomp, and formality; he is full of pride and self-love. He is miserly; polite, but with ceremony; he suffers most through the refusal of others to fall in which his pretensions. In one word, the choleric temperament is the least happy, because it is the most likely to call forth opposition to itself.

-

The Phlegmatic Temperament. Phlegma means lack of emotion, not laziness; it implies the tendency. to be moved, neither quickly nor easily, but persistently. Such a person warms up slowly, but he retains the warmth longer. He acts on principle, not by instinct; his happy temperament may supply the lack of sagacity and wisdom. He is reasonable in his dealing with other people, and usually gets his way by persisting in objectives while appearing to give way to others.

In the end, Greek humor theory proved to be no more valid that astrology: it was an early victim of the scientific revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries. Nevertheless, it formed the basis for the study of the psychophysiological correlates of emotion -- the search for patterns of somatic activity uniquely corresponding to emotional experiences. Moreover, the classic fourfold typology laid the basis for a major tradition in the scientific study of personality, which emerged around the turn of the 20th century. We shall examine each of these topics in detail later. First, however, we should examine other typological schemes that are prominent today.

The Four Temperaments

For a history of the humour theory of temperament in medicine and psychology, see Passions and Tempers: A History of the Humours by Noga Arikha (Ecco/HarperCollins, 2007; reviewed by Sherwin P. Nuland in the New York Times Book Review, 07/08/2007).

The

classic fourfold typology, derived from ancient Greek humour

theory, is often referred to as The Four Temperaments.

Under that label, it has been the subject of a number of

artworks. In Christ Crowned with Thorns (c.1479,

also called the Mocking of Christ), Jesus is

tormented by four men who represent the four temperaments:

clockwise from the upper left, choleric, sanguine,

phlegmatic, and melancholic.

The

classic fourfold typology, derived from ancient Greek humour

theory, is often referred to as The Four Temperaments.

Under that label, it has been the subject of a number of

artworks. In Christ Crowned with Thorns (c.1479,

also called the Mocking of Christ), Jesus is

tormented by four men who represent the four temperaments:

clockwise from the upper left, choleric, sanguine,

phlegmatic, and melancholic.

In music, a humoresque is a term given to a light-hearted musical composition. But Robert Schumann's "Humoreske in Bb",Op. 20 (1839), is a suite based on the four classical humours.

The German composer Paul Hindemith also wrote a suite for piano and strings -- a actually, a theme with four variations -- entitled The Four Temperaments (1940), which was choreographed for the Ballet Society, the forerunner of the New York City Center Ballet by George Balanchine (1946).

Modern Clinical Typologies

With the emergence of psychology as a scientific discipline separate from philosophy and physiology in the late 19th century, a number of other typological schemes were proposed. Most of these had their origins in astute clinical observation by psychiatrists and clinical psychologists rather than in rigorous empirical research. However, all of these were explicitly scientific in intent, in that their proponents attempted to develop a body of evidence that would confirm the existence of the types.

Freud

Sigmund Freud (1908), a Viennese psychiatrist whose theory of personality we will consider later in some detail (see "Freud's Psychoanalytic Theory"), claimed that adults displayed constellations of attributes whose origins could be traced to early childhood experiences related to weaning, toilet training, and sexuality. Freud himself described only one type -- the anal character, which displays excessive frugality, parsimony, petulance, obstinacy, pedantry, and orderliness.

Freud's followers, working along the same lines, elaborated a wide variety of additional types such as the oral, urethral, phallic, and genital (Blum, 1953; Fenichel, 1945; Shapiro, 1965). Here are some examples:

-

The Oral Character. The oral character ... is extremely dependent on others for the maintenance of his self-esteem. External supplies are all- important to him, and he yearns for them passively .... When he feels depressed, he eats to overcome the emotion. Oral preoccupations, in addition to food, frequently revolve around drinking, smoking, and kissing (Blum, 1953, p. 160).

-

The Urethral Character. The outstanding personality features of the urethral character are ambition and competitiveness ... (Blum, 1953, p. 163).

-

The Phallic Character. The phallic character behaves in a reckless, resolute, and self-assured fashion ....The overvaluation of the penis and its confusion with the whole body ... are reflected by intense vanity, exhibitionism, and sensitiveness .... These individuals usually anticipate an expected assault by attacking first. They appear aggressive and provocative, not so much from what they say or do, but rather in their manner of speaking and acting. Wounded pride ... often results in either cold reserve, deep depression, or lively aggression (Blum, 1953, p. 163).

Jung

C.G. Jung (1921), an early follower of Freud, developed an eightfold typology constructed from two attitudes and four functions. In Jung's system, the attitudes represented different orientations toward the world: the extravert, concerned with other people and objects; and the introvert, concerned with his or her own feelings and experiences. The functions represented different was of experiencing the objects of the attitude: thinking, in which the person was engaged in classifying observations and organizing concepts; feeling, in which the person attached values to observations and ideas; sensing, in which the person was overwhelmingly concerned with concrete facts; and intuition, in which the person favored the immediate grasping of an idea as a whole.

The typical opposition I have described is characteristic of the introverted and extraverted attitudes. The first, if normal, is revealed by a hesitating, reflective, reticent disposition, that does not easily give itself away, that shrinks from objects, always assuming the defensive, and preferring to make its cautious observations from a hiding-place. The second type, if normal, is characterized by an accommodating, and apparently open and ready disposition, at ease in any given situation. This type forms attachments easily, and ventures, unconcerned and confident, into unknown situations, rejecting thoughts of possible contingencies. In the former case, manifestly the subject, in the latter, the object, is the decisive factor (Jung, 1917).

The four functional types correspond to the obvious means by which consciousness obtains its orientation. Sensation, sense perception, tells us that something exists; thinking tells you what it is; feeling tells you whether it is agreeable or not; and intuition tells you whence it comes and where it is going (Jung, 1917).

In each person, one attitude and one function dominated over the others, resulting in eight distinct personality types. These attitudes and functions, inferred by Jung on the basis of his clinical observations, may be measured by a specialized psychological test, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI; Myers, 1962).

Functions |

Attitudes |

|

Introverted |

Extraverted |

|

Sensing |

||

Thinking |

||

Feeling |

||

Intuiting |

||

A note of caution: the MBTI is very popular among human-resource managers, and on self-discovery and self-help websites, but it isn't a very good personality inventory. For example, although "types" are supposed to be permanent, even innate, people's scores on the MBTI can vary widely if taken on more than one occasion. For more on the history, use, and validity of the MBTI, see The Personality Brokers by Merve Emre (2018) and The Cult of Personality Testing" by Annie Murphy Paul (2004). Also "Can You Type?" by Louis Menand, New Yorker, 09/10/2018.

Sheldon

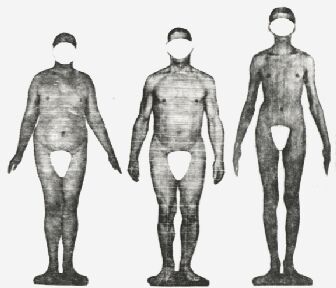

Another important typology was developed by Sheldon (1940,1942), as an extension of the constitutional psychology introduced by the German psychiatrist, Ernst Kretchmer (1921). Kretchmer and Sheldon both asserted that there was a link between physique and personality.

On the basis of his anthropometric studies of the bodily

builds, in which he took various measurements of the head,

neck, chest, trunk, arms, legs, and other parts of the body,

Sheldon discerned three types of physique reflecting both the

individual's constitutional endowment and his or her current

physical appearance:

On the basis of his anthropometric studies of the bodily

builds, in which he took various measurements of the head,

neck, chest, trunk, arms, legs, and other parts of the body,

Sheldon discerned three types of physique reflecting both the

individual's constitutional endowment and his or her current

physical appearance:

-

endomorphs possessed soft, round features;

-

mesomorphs were hard and rectangular in appearance; and

-

ectomorphs were thin and fragile.

In his Atlas of Men (1954), Sheldon introduced a procedure by which people could be categorized based on ratings of endomorphy, mesomorphy, and ectomorphy. As you might expect, Sheldon also planned to produce an Atlas of Women, as well as an Atlas of Children, but both projects were unfinished at the time of his death.

On the basis of personality data, including questionnaires and clinical interviews, Sheldon likewise discerned three types of temperament:

-

viscerotonia, featuring sociability and tolerance;

-

somatotonia, featuring physical vigor and adverturesomeness; and

-

cerebrotonia, featuring restraint and self-consciousness.

Sheldon also found a relationship between the physical and psychological typologies:

-

endomorphs tended toward viscerotonia,

-

mesomorphs toward somatotonia, and

-

ectomorphs toward cerebrotonia.

Sheldon felt that this relationship reflected the common genetic and biochemical determinants of both physique and temperament, though of course the relationship could also reflect common environmental sources. For example, one's physique may place some limits on the kinds of activities in which one engages; or, alternatively, social stereotyping may limit the kinds of activities in which people with certain physiques are involved.

Actually, it turns out that the relationship is a lot simpler than that. It turns out that Sheldon's raters (who included Sheldon himself) were not blind to his theory. They knew that Sheldon had hypothesized that endomorphs tended to be viscertonic (not to mention that the stereotype of the jolly fat person has been around for a long time). And there is every reason that they saw what they were supposed to see. The fact that Sheldon's raters weren't blind obviates the whole research enterprise, and so you wonder why they even bothered doing the study. It's of interest to note that Sheldon did his studies on undergraduates in the "Ivy League" and "Seven Sisters" schools, based on the infamous "posture photographs" that these schools during freshman orientation week (see"The Great Ivy League Nude Posture Photo Scandal" by Ron Rosenbaum,New York Times Magazine, 01/15/1995).You can't help but wonder whether the whole enterprise was little more than an excuse to look at pictures of college students in their underwear (or less!).

Horney

Another follower of Freud, Karen Horney (in Our Inner Conflicts, 1945), proposed a three-category system based on characteristic responses of the developing child to feelings of helplessness and anxiety.

-

The compliant type fears rejection and criticism, needs, affection and approval, and subordinates him- or herself to others.

-

The aggressive type sees affection, sympathy, and trust as signs of weakness, and seeks mastery, domination, and self- glorification.

-

The detached type fears the obligations and influences that come with ordinary social relations, and thus avoids situations involving. competition and intimacy.

Sociological Typologies

Other typological systems have resulted from the analysis of whole societies rather than of individual clinic patients. Although sociology is an empirical science, these typologies are not. typically determined quantitatively. Rather, like their clinical counterparts, they represent the investigator's intuitions about the kinds of people who inhabit a particular culture.

Spranger

The German philosopher and psychologist Eduard Spranger did not, strictly speaking, postulate a typology. Rather, he was interested in describing various coherent sets of values which a person could use to guide his or her life. However, the argument was presented in a book entitled Types of Men (1914/1928), so the descriptions below (as summarized by Allport & Vernon, 1931), seem to fit our purposes.

1. The Theoretical. The dominant interest of the theoretical man is the discovery of truth. In the pursuit of this goal he characteristically takes a "cognitive" attitude, one that looks for identities and differences; one that divests itself of judgments regarding the beauty or utility. of objects, and seeks only to observe and to reason .... His chief aim in life is to order and to systematize his knowledge.

2. The Economic. The economic man is characteristically interested in what is useful. Based originally upon the satisfaction of bodily needs (self-preservation), the interest in utilities develops to embrace the practical affairs of the business world -- the production, marketing, and consumption of goods, the elaboration of credit, and the accumulation of tangible wealth. This type is thoroughly "practical" ....

3. The Esthetic. The esthetic man sees his highest value in form and harmony. Each single experience is judged from the standpoint of grace, symmetry, or fitness. He regards life as a manifold of events; each single impression is enjoyed for its own sake. He need not be a creative artist; nor need he be effete; he is esthetic if he but finds his chief interest in the artistic episodes of life ....

4. The Social. The highest value for this type is love of people, whether of one or many, whether conjugal, filial, friendly, or philanthropic. The social man prizes other persons as ends, and is therefore himself kind, sympathetic, and unselfish. He is likely to find the theoretical, economic, and esthetic attitudes cold and inhuman. In contrast to the political type, the social man regards love as itself the only suitable form of power, or else repudiates the entire conception of power as endangering the integrity of personality. In its purest form the social interest is selfless and tends to approach very closely to the religious attitude.

5. The Political. The political man is interested primarily in power. His activities are not necessarily within the narrow field of politics; but whatever his vocation be betrays himself as a Machtmensch. Leaders in any field generally have high power value. Since competition and struggle play a large part in all life, many philosophers have seen power as the most fundamental of motives ..... There are, however, certain personalities in whom the desire for a direct expression of this motive is uppermost, who wish above all else for personal power, influence, and renown.

6. The Religious. The highest value for the religious man may be called unity. He is mystical, and seeks to comprehend the cosmos as a whole, to relate himself to its embracing totality .... Some men of this type are "immanent mystics", that is, they find in the affirmation of life and in active participation therein their religious experience. A Faust with his zest and enthusiasm sees something divine in every event. The "transcendental mystic", on the other hand, seeks to unite himself with a higher reality by withdrawing from life; he is the escetic, and like the holy men of India, finds the experience of unity through self-denial and meditation.

Spranger's work formed the basis for an assessment of individual differences in human values by Allport and Vernon (1931; see also Allport, Vernon, & Lindzey, 1970).

Riesman

In one of the most influential pieces of social criticism written since World War II, David Riesman's the Lonely Crowd (1950) analyzed the impact of industrial development on personality.

-

The members of underdeveloped societies, especially if literacy was not widespread, tended to be tradition-directed. Such people define themselves in terms of age, clan, or caste, and adhere to longstanding patterns of behavior rather than seeking new solutions to the problems which they face.

-

As societies begin to mature and the quality of life improves through agricultural and industrial development, the individual is confronted by opportunities for upward mobility, and a wide range of choices concerning his or her vocation. The inner-directed individual is able to cope with these new alternatives, even in the absence of traditional institutions, because he or she has internalized goals set by his or her parents.

-

At some point, agricultural and industrial development reach such a point that the members of a society accumulate both a fair amount of wealth and a substantial share of leisure time; service industries begin to supplant production.; Under these conditions, a "new middle class" emerges which may be characterized as other-directed. For these individuals, choices and goals are determined by other people, and especially the media, rather than by their families or traditional institutions. Note that tradition-, inner-, and other-directed people are not different in conformity; rather, they are different in terms of what they conform to.

Riesman argued that the other-directed type predominated in postwar American society. But to the extent that economic and cultural conditions vary in a pluralistic society, we might still expect to find a fair representation of the other types as well.

Fromm

Fromm, who was as much influenced by Karl Marx as by Sigmund Freud, and by economics as much as by psychopathology, offered a list of five basic character types, which result from differential socialization rather than from childhood anxieties.

-

The receptive type feels inferior and insignificant, and acquiesces out of a fear of others.

-

The exploitative type also feels weak and helpless, and tries to gain advantage over others by force and cunning.

-

The hoarding type fears competition and the threats that come with it, and seeks security by refusing to share with others.

-

The marketing type lacks originality and self-confidence, and tries to conform to the expectations of others.

These types of adjustment are labeled "unproductive" by Fromm, because they prevent the individual from realizing his or her full potential.

-

The productive type, by contrast, uses these nonproductive strategies in productive ways -- transforming receptivity into friendliness, hoarding into conscientiousness, etc. -- and uses them to enjoy a life in which he or she is creative, concerned for others, capable of loving and capable of being loved

From Types to Traits

The typologies of Theophrastus and his successors -- Jung, Sheldon, Reisman, and others -- are satisfying from one standpoint, because they seem to capture the gist of many of the people whom we encounter in our everyday lives. However, from a scientific point of view they are unsatisfying on at least two counts.

First, it is hard to specify the rules by which the various type. concepts have been defined. According to the classical view of categorization which has dominated typological thinking since the time of Aristotle, concepts label proper sets of attributes which are single necessary and jointly sufficient to define some category. Each of these defining attributes must be present in every instance, giving the category an "all-or-none" quality. Thus, for example, a triangle is defined as a closed figure with three sides and three angles. Either each feature is present or it is not. Any geometrical form which possesses all of these properties is a triangle; any figure which lacks even one of them is not. Proper sets may be arranged in a hierarchy based on class inclusion relations, in which subcategories ma be formed by adding on new defining features. Thus, the superordinate category "geometrical figure" may be divided. into "points" (having no dimensions), "lines" (having only one dimension), "planes" (having two dimensions), and "solids" (having three dimensions). Shapes may be divided into triangles, quadrilaterals, and the like. Triangles may be divided into equilateral or isosceles, right or acute; quadrilaterals can be divided into parallelograms, rhombuses, trapezoids, and trapeziums; etc. Such hierarchies show perfect nesting: all instances of subcategories also possess the defining features of. the relevant superordinate category.

Such an approach works well for geometrical patterns, but applying it to people presents a number of different problems. First, human attributes are not generally present in an all-or-none manner, but are continuously distributed over an infinite series of gradations. The most prominent exceptions are gender and blood type; but the claim of continuity holds true for other strictly physical dimensions such as height, girth, and skin color -- How tall is tall? How fat is fat? How black is black? -- and this is all the more the case for psychological attributes. All sanguines may be sociable, but some people are more sociable than others. The notion that some people may be more sanguine than others, which is what this fact implies, is inconsistent with the classical view of categorization. Moreover, many individuals display the features of contrasting categories. If sanguines are sociable, and cholerics egocentric, what do we make of a person who is both sociable and egocentric? We are reminded of the entomologist who found an insect which he could not classify, and promptly stepped on it. The problem of partial and combined expression of type features, once recognized and taken seriously, was the beginning of the end for type theories.

A second problem has to do with the sheer number of different typological schemes that have been proposed. Most of these typologies are eminently plausible: each of us knows some extraverts and some sanguines, thinkers and intuiters, somatotonics and other-directed people. The reader who has stuck with this chapter so far may also have discovered that some (perhaps many or most) of his or her acquaintances can be classified into several different type categories, depending on which features are the focus of attention. This puts us in the curious position that a person's type can change. according to the mental set of the observer, even if his or her behavior has not changed at all. As Allport (1937) noted, no typology can encompass all the attributes of a person:

Whatever the kind, a typology is always a device for exalting its author's special interest at the expense of the individuality of the life which he ruthlessly dismembers .... This harsh judgment is unavoidable in the face of conflicting typologies. Certainly not one of these typologies, so diverse in conception and scope, can be considered final, for none of them overlaps any other. Each theorist slices nature in any way he chooses, and finds only his own cuttings worthy of admiration .... What has happened to the individual? He is tossed from type to type, landing sometime in one compartment and sometime in another, often in none at all (p. 296).

As this passage makes clear, Allport's objection to typologies was that they are biosocial rather than biophysical in nature. He held that types are cognitive categories rather than attributes of people: they exist in the minds of observers rather than in the personalities of the people who are observed. For Allport, as for many other personologists who wish to base a theory of personality on how individuals differ in essence, types appear. to be a step in the wrong direction.

The Dimensional Solution

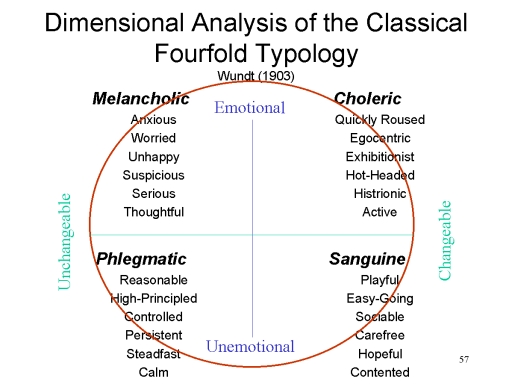

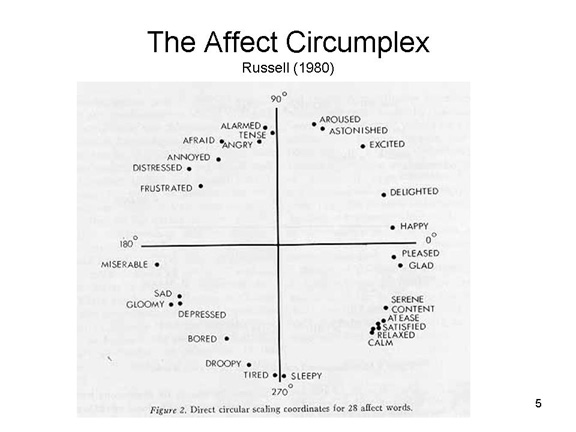

One of

the founders of modern scientific psychology, Wilhelm Wundt

(1903), offered a solution to both these dilemmas. Wundt was a

structuralist, primarily concerned with analyzing mental life

into its basic elements. While his work emphasized the

analysis of sensory experience, he also turned his attention

to the problems of emotion and personality. Wundt argued that

the classic fourfold typology of Hippocrates, Galen, and Kant

could be understood in terms of emotional arousal.

One of

the founders of modern scientific psychology, Wilhelm Wundt

(1903), offered a solution to both these dilemmas. Wundt was a

structuralist, primarily concerned with analyzing mental life

into its basic elements. While his work emphasized the

analysis of sensory experience, he also turned his attention

to the problems of emotion and personality. Wundt argued that

the classic fourfold typology of Hippocrates, Galen, and Kant

could be understood in terms of emotional arousal.

-

Cholerics and melancholics were disposed to strong emotions, while sanguines and phlegmatics were disposed to weak ones.

-

Similarly, the emotions were quickly aroused in cholerics and sanguines, but only slowly in melancholics and phlegmatics.

Instead of slotting people into four discrete categories, Wundt proposed that people be classified in terms of two continuous dimensions reflecting their characteristic speed and intensity of emotional arousal. In this way, Kant's categorical system was transformed into a dimensional system, in which individuals could be located not in categories but as points in two-dimensional space. The classic fourfold types described those individuals who fell along the diagonals of the system.

Actually, it appears that Wundt's solution was presaged by the ancients themselves, who believed that two bipolar qualities underlay the classic fourfold typology: moist vs. dry, and hot vs. cold (Arikha, 2007):

-

the choleric temperament is characterized by dry heat;

-

the melancholic temperament is characterized by dry cold;

-

the phlegmatic temperament is characterized by moist cold;

-

and the sanguine temperament by moist heat.

Abandonment of categorical types in favor of a dimensional scheme proposed by Wundt seemed to allow the differences. between people to be represented more accurately. Such a solution also appealed to Allport, who celebrated the individual and who was more interested in studying a person's unique combinations of attributes than in studying whole classes of people or people in general. This development initiated a tradition in the scientific study of personality known as trait psychology.

Allport and the Doctrine of Traits

The seminal discussion of the trait concept in personality was provided by Allport (1937). Allport rejected the point of view, which was quite popular at the time, that personality was comprised of countless individual habits, or manners of responding to particular situations. Anticipating a position that was to become popular later (see "Situationism"), he also rejected the notion that the consistency in behavior across different situations --the primary evidence for individual differences in personality, from a trait point of view -- was due to the similarity of the situations involved (that is, the generalization of habits from one situation to another). Rather, he argued that habitual responses and situations were united. by personality traits.

Allport defined a personality trait as

a generalized and focalized neuropsychic system ... with the capacity to render many stimuli functionally equivalent, and to initiate and guide consistent (equivalent) forms of adaptive and expressive behavior (1937, p. XXX).

According to this view, traits are internal to the person, located somewhere in the brain, and they dispose the person to behave in a similar way across a variety of apparently different situations. Traits, as biophysical entities, mediate between stimuli and the person's response to them. This biophysical view has been generally endorsed by those working within the trait tradition, and may be termed the doctrine of traits.

The doctrine begins with the twin assumptions that behavior is internally consistent across time and across different situations. It goes on to explain behavioral consistency in terms of the presence, in the brain, of generalized dispositions to behave. in certain ways. Traits can be abstracted from observing the individual's behavior in a variety of situations and -- once assessed -- may be used to confidently predict what a person will do in a new situation. It is important to note that the doctrine of traits, as articulated by Allport, does not hold that traits are biological in origin -- though at least one prominent contemporary investigator of traits, Eysenck (ref), has insisted that true personality traits are part of the individual's genetic endowment, just like physical traits such as gender or blood type -- or at least height and weight. Traits may indeed be acquired genetically, according to the doctrine, but they may also be acquired through experience. However they are acquired, however, they have physical existence in the brain as -- perhaps -- patterns of neurons. This is the meaning of the biophysical view of traits.

In articulating his version of the theory of traits, Allport began by distinguishing between two types of scientific psychology: the nomothetic, in which there is a search for general principles of (say) perception, memory, or social behavior; and the idiographic, in which there is an attempt to understand some individual man or woman. According to Allport, the latter is the unique task of personology: it cannot be accomplished by the study of people-in-general, which is the task of the other subdisciplines of psychology; or by studying smaller classes of individuals, which is the goal of the typologists.

No two men possess precisely the same trait. Every life has a unique history and in the course of its developmental struggle it attains correspondingly unique patterns of mental organization. Traits must be discovered in each individual life separately. They cannot be abstracted from a population (Allport, 1937, pp. XXX-XXX).

Somewhat paradoxically, perhaps, Allport's best-known empirical efforts are strictly nomothetic investigations: of prejudice, in which he studied "mind-in-general" (Allport, 1954); of values, in which he employed Spranger's typology to classify subjects (Allport & Vernon, 1931); and of nonverbal behavior, in which subjects were ranked on various dimensions (Allport & Vernon, 1933). Allport celebrated the individual, but as a scientist he could not resist the pull of the nomothetic. Nevertheless, he was also able to show how nomothetic science might be done in the study of values, because his personality scale was ipsative, giving information about the organization of values. within each individual, as well as normative, giving information about the relative standings of each individual on the scales. In the scale, the subject had to express his/her preference for one of two statements, each representing a different value. Thus, over a large number of such choices, a hierarchical ordering would be apparent, ranking the values from highest to lowest in the life of each individual subject.

Allport did acknowledge that a few traits might be shared by all individuals -- common traits representing modes of adjustment which all individuals must develop to some degree. As an example of common traits, he lists ascendance-submission, introversion-extraversion, perseverance, and generalized social attitudes and interests. His clear emphasis, however, was on personal traits which comprise the person's "unique patterned individuality" (REF). Among the personal traits Allport distinguished three levels of importance. Rarely, he held, some trait will be so pervasive in the individual's. thought and action as to qualify as cardinal. For everyone, however, there are some 5-10 central traits which are the most important features of his or her personality. These are supplemented by some number of secondary traits which are expressed very infrequently, or only in very specific situations. This classification is as far as Allport will go: he neither sets a firm number of traits in each category, nor attempts to produce a finite, exhaustive list of terms from which the individual's traits may be selected (aside from the 17,953 in the Allport-Odbert list).

Allport held that traits were discovered in individuals through observations of consistency in behavior, and were inferred by considering both the behavior and the situation which evoked it. Judgments concerning traits, then, represented intuitions on the part of the observer which could be tested through continued observation -- through either some contrived laboratory test or continued systematic sampling f real-world behavior. His emphasis on discovering and naming traits is important, because Allport insisted that traits could not be measured in the terms favored by factor-analysts and others who took a quantitative approach to personality assessment. Measurement requires some comparative standard: Sue is friendlier than Joe but less friendly than Alex. But according to Allport different people possess different constellations of traits, not just the same traits in different degrees, so that such a comparison is impossible. Even the so-called common traits are modified by the context of the individual's personal traits, so that comparing two people in terms of extraversion-introversion is like comparing apples and oranges.

Modern Variants

The concept of a personality trait goes back at least to the time of Galton (who was, remember, Darwin's cousin), and the analogy between mental and physical attributes -- the idea that characteristic mental features, as well as characteristic physical features, were at least in part genetically determined, and thus could be subject to evolution by natural selection. In fact, if we turn to the Trait-Book maintained by the Eugenics Records Office (1919), we'll see personality traits such as love of fishing,aggressiveness, and religiosity listed right there with albinism,eczema, and ingrowing toenails.

But just what is a personality trait? Allport (1937) gave one answer -- "a generalized and localized neuropsychic system ... with the capacity to render many stimuli functionally equivalent, and to initiate and guide consistent (equivalent) forms of adaptive and expressive behavior".

Wiggins (1974, 1997) offered a contemporary analysis of the concept of a personality trait.

In the first place, traits are considered to be attributes of behavior, that describe the qualities of actions. Consider, for example, the following sentences:

-

John pushed the boy aggressively.

-

John pushed the boy gently.

These sentences describe two quite different actions, but they refer to qualities of action, not to qualities of persons. John may be a very gentle person who, for some reason, pushed the boy aggressively -- or vice-versa.

As Barbara Woodhouse would say, "There are no bad dogs" -- just bad dog behaviour (she's English).

The example highlights the distinction that the philosopher John Searle (1969) draws between brute facts and institutional facts.

-

Brute facts lend themselves to direct observation.

-

Institutional facts presuppose the existence of human institutions, which create rules, which give special meaning to brute facts. Thus, a brute fact X counts as an instance of an institutional fact Y in the context of C. In this case, we are less interested in the ontological status of an institutional fact than we are in the underlying rule.

So, is aggressive pushing somehow objectively different from gentle pushing? If so, what topographical features make the difference. Or is aggressive and gentle pushing in the eye of the beholder? If so, what are the the rules that give rise to the characterization of a push as aggressive rather than gentle?

Alternatively, traits can be considered to be attributes of persons, not just of their behavior.So, now consider the following sentences:

-

John is aggressive.

-

John is gentle.

These sentences describe two quite different people -- aggression or gentility is ascribed to the person, not just his behavior. John may be an aggressive person who sometimes behaves gently, or vice-versa. But, deep down, he's aggressive (or gentle). So what do we mean when we say someone is aggressive or gentle?

-

The philosopher Gilbert Ryle (1949) defined traits as causal dispositions -- as dispositions to behave in a particular way, whether aggressively or gently. These predictions are probabilistic in nature. If John is aggressive, we don't necessarily expect him to behave aggressively in each and every situation, but we do expect him to be aggressive more often than not. Thus,

-

When we say that John is aggressivewe mean that John is disposed to act aggressively.

-

When we say that John is gentle we mean that John is disposed to at gently.

Ryle's view seems closest to Allport "biophysical" view -- that traits have actual existence as determinants of behavior. Probabilistic determinants to be sure, but determinants nonetheless.

-

-

On the other hand, another philosopher, Stuart Hampshire (1953) defined traits as categorical summaries of behavior. We don't know where this behavior comes from, exactly, but we do believe that it is aggressive or gentle. Categorical summaries differ from causal dispositions in that there is no implication that the trait caused a certain kind of behavior to occur. All we can say is that a certain type of behavior tends to occur.

-

When we say that John is aggressive we mean that John tends to act aggressively.

-

When we say that John is gentle we mean that John tends to act gently.

In either case, we're just summarizing the qualities of John's behavior. We're not making any causal inference about why he behaves that way. Hampshire's view seems closest to Allport's "biosocial" view -- that traits are simply labels that we give to behavior, and thus have only nominal existence. Traits name behaviors, but they don't cause behaviors.

-

In either case, though, when traits label attributes serve as predictors of behavior.

-

The predictions are probabilistic in nature -- we don't expect John to behave aggressively or gently in each and every instance, but we do expect him to tend to behave that way.

-

And the predictions are of relative behavior -- we expect John to behave more aggressively, or more gently, than the average person would in the same situation.

In addition, traits serve as explanations of behavior.

-

John pushed the boy aggressively because he is aggressive, and thus disposed to act in an aggressive manner.

-

John pushed the boy gently because he is gentle, and thus disposed to act in a gentle manner.

Assigning a trait label to a person implies that trait-relevant behavior is characteristic of him, and not unexpected.

-

The behavior is phenotypic in nature -- it is manifest, on the surface, publicly observable.

-

The trait in question is genotypic in nature -- it is latent, below the surface, not publicly observable -- but it is the source of the publicly observable behavior.

Now, not everyone agrees with this. Personality and social psychologists disagree vehemently about whether traits are causal dispositions or social labels. For Wiggins himself, traits are social labels that reflect institutional (social, cultural) rules for classifying behavior. And for Wiggins, the organization of traits reflects these same institutional rules.

But the traditional trait theories of personality assume, with Galton, that traits have actual, not merely nominal, existence; and that they are causes of behavior, not merely labels.

Whether you take the biophysical or the biosocial view, the concept of the personality trait arises from our need to isolate elements of personality -- to uncover units that are measurable, that form the basis for describing people, comparing them to each other, and predicting their future behavior.

So what are the basic traits of personality?

The Problem of Trait-Names

The adoption of a trait scheme for the classification of people solved the problem of types, but it raised a new problem: how many traits are there? Allport and Odbert (1936) clearly identified this difficulty when they prepared an exhaustive list of dictionary entries that could be used to distinguish one individual from another. They turned up some 17,953 words in the 1925 Webster's New International Dictionary!

-

Some of these words represented fairly generalized, stable characteristics of the person (4,504 items) such as aggressive,introverted, and sociable.

-

Still others (4,541 items) represented more transient states of mood or mind such as abashed,gibbering, and rejoicing.

-

Another category contained social judgments (5,226 items) such as insignificant,acceptable, and worth.

-

And finally, there was a grab-bag (3,682 items) of explanations of behavior (e.g.,pampered,crazed), physical qualities (e.g.,roly-poly,red-headed), and talents or capacities (e.g.,able,gifted).

Actually, Allport and Odbert miscounted: due to a proof reading error, they used the same number twice, so that their actual list contained 17,954 trait terms. But who's counting?

In addition to the sheer number of trait names, Allport and Odbert identified a further problem: the list of trait names was not stable. Cultural change contributed new terms (e.g.,robotlike), some old terms acquired new meanings (e.g.,gay), and still others fell into disuse. Still further, it was clear that some of the 17,953 terms were related to each other, either as synonyms or as close associates.

This situation is compounded because the list of possible trait names is growing. Norman (1967), surveying the third edition of the same dictionary used by Allport and Odbert (1936), brought their list up to approximately 40,000 items -- roughly 10% of the entire vocabulary of English. Editing the list to remove obscure and archaic terms (e.g.,acaroid,raptril), loose metaphors (e.g.,canine, nebulous), physical features (e.g.,chubby,pallid), evaluative words (e.g., awful,outstanding), and quantifiers (e.g.,normal,mediocre), reduced this list to 18,129 words -- which is a lot of words. Of this number, some 2800 were taken to describe "stable, biophysical traits".

Clearly, if type theory was too simple to accommodate individual differences, trait theory was in danger of becoming too complex. Some method was required to organize the chaos of descriptive terms, reduce the list of lexical entries to a manageable number, and represent the relationships among various trait-names. With the development of mathematical statistics around the turn of the century, such a method was found: factor analysis.

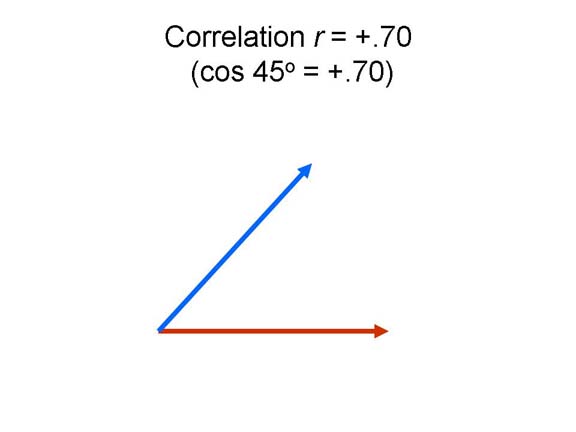

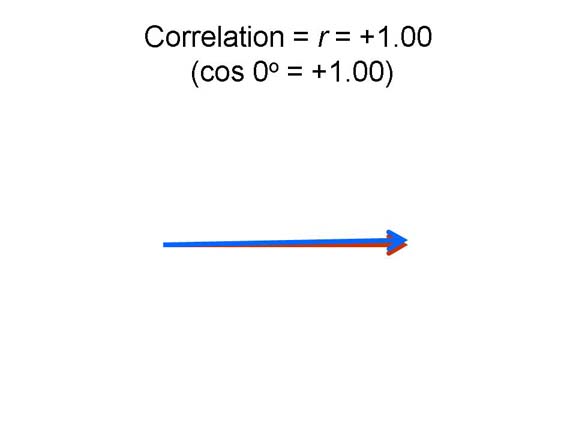

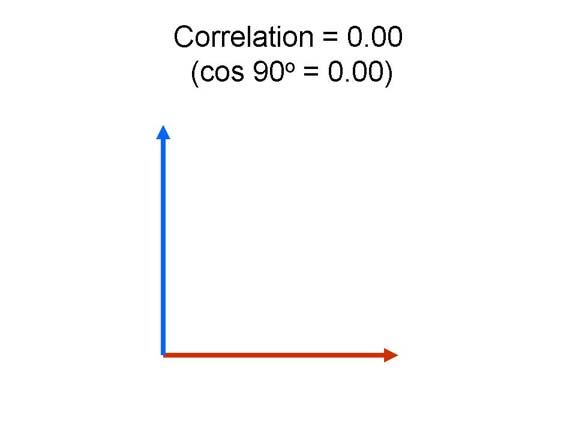

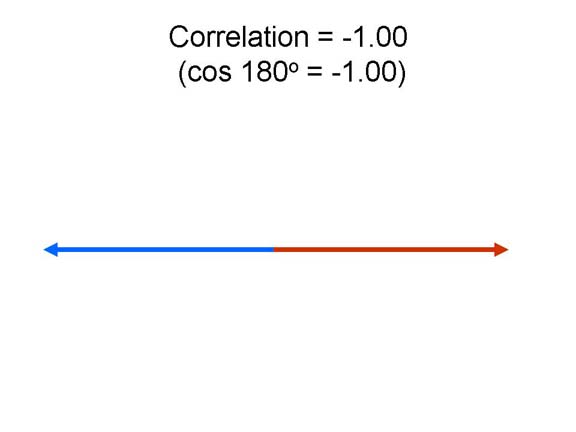

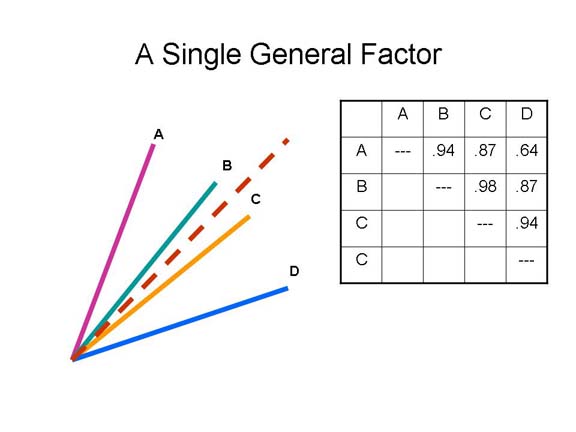

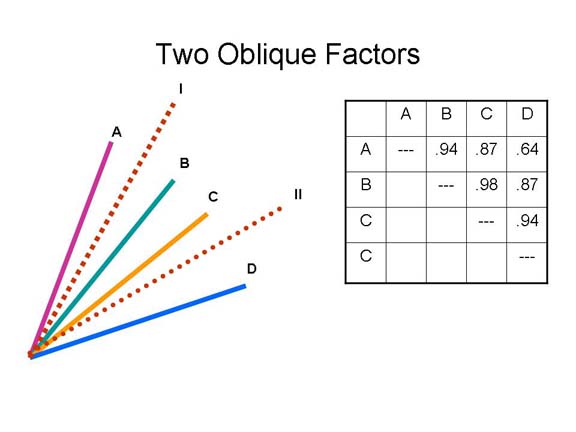

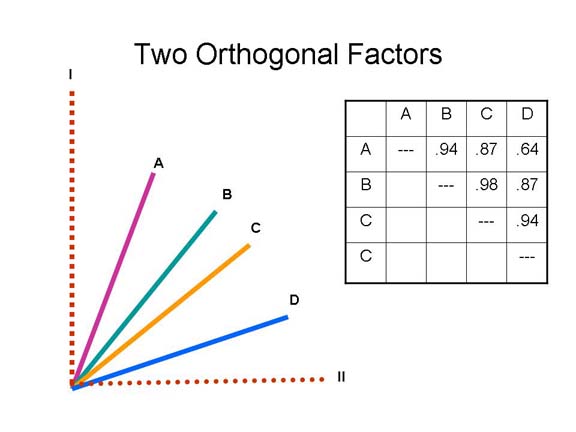

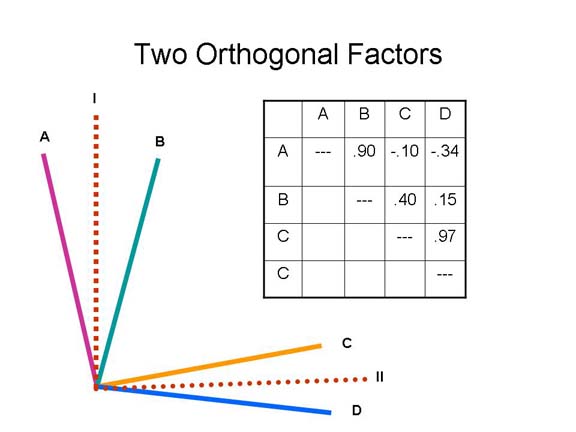

The Technique of Factor Analysis

Factor analysis is based on the correlation coefficient (r), a statistic which expresses the direction and degree and of relationship between two variables. Correlations can vary from negative (high scores one variable are associated with low scores on another variable), through zero (no relationship between variables), to positive (high scores on one variable are associated with high scores on the other). In graphic terms, a correlation may also be expressed graphically as the cosine of the angle formed by two vectors representing the variables under consideration.

Now imagine a matrix containing the correlations between 100 different variables -- or, worse yet, a figure representing these correlations graphically. This would amount to 4950 correlations or vectors -- clearly too many even hope to grasp. Factor analysis reduces such a matrix to manageable size by summarizing groups of highly correlated variables as a single factor. There are as many factors as there are distinct groups of related variables.

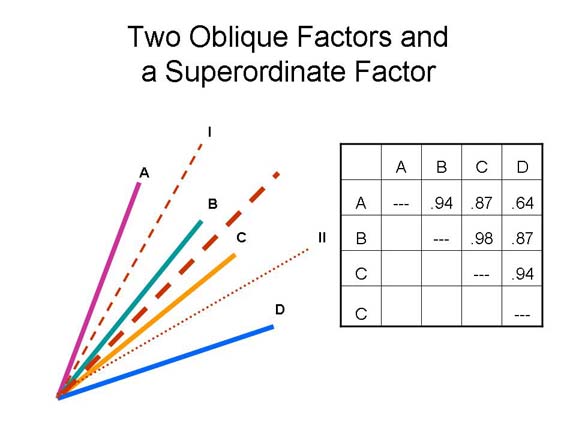

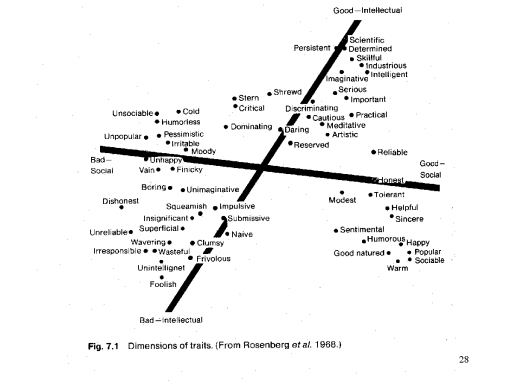

Consider the four variables whose correlations are represented in the matrix and graph shown below.

How does this relate to personality? Some investigators (though not, as we shall see, Allport himself) have attempted to use factor analysis to solve the problem of trait names by editing the trait lexicon. Essentially, their procedure is to rate people on a large number of traits, and then to intercorrelate and factor-analyze these ratings. Related traits, then, should hang together as factors. By referring to factors of personality, rather than individual trait-names, they hoped to reduce the set of traits to a small manageable set which would permit the efficient and accurate description of individual differences in personality. The assumption, following Allport (1937), is that trait names come into existence because people possess the qualities being referred to; and these labels remain in ordinary language because these qualities. have important consequences for social interaction, and are routinely perceived by other people. ostensibly related to these traits.

Types of Factor Analysis

In the early days, factor-analyses were performed by hand, using protractors and graph paper. Nowadays they are done on high-speed computers, but the procedure is mathematically the same. Generally speaking, the choice among the three major forms of factor analysis is dictated largely by the nature of the interitem correlations, as well as by personal taste.

-

When it's clear that all the items are highly intercorrelated, the investigator may wish to summarize them all with a single general factor. Where some items are uncorrelated with others, or when many of the intercorrelations are relatively low, the investigator may wish to extract multiple factors. In the latter case, the factors may be orthogonal or oblique.

-

If orthogonal, the factors are constrained so that they are uncorrelated with each other; if oblique, the factors are allowed to correlate with each other. The result is a very elegant solution -- it's very clean.

-

If oblique factors are permitted, of course, the process can be continued by constructing higher-order or superordinate factors which summarize the relations between primary or subordinate factors.

Allport (1937) has offered two conceptual objections to factor-analytic studies of personality.

-

First and foremost, he argued that it is unreasonable to assume that all personalities are composed of the same elements, varying only in degree. From his point of view, analyzing large numbers of subjects to extract the "basic dimensions" of personality inevitably leads to mixing individual sets of dispositions -- producing an "average personality" which is a complete abstraction, not representative of any individual in the group.

-

Similarly, he argued that the search for a common structure of personality, shared by all individuals, violates the assumption of individual development. If development entails the divergence of the maturing organism from the biological and psychological structures of infancy, than to focus on what is common among adults necessarily misses the unique products of the individual's biological endowment and historical experience.

Allport has also articulated some methodological as well as conceptual criticisms of the search for traits through factor analysis.

-

First, he noted that in many analyses the factors combine items which make no psychological sense -- as indicated, for example, in the difficulty which the investigator often has in coming up with appropriate names for his or her factors. This gives them the appearance of mathematical artifacts, rather than substantial psychological constructs.

-

Moreover, Allport criticized the assumption made by most factor-analysts (though not all of them) that the factors of personality must be independent of each other. To the contrary, Allport asserts that because personality is an organic, unified whole, all the individual's traits must be related through some organizational structure. However, most personologists do not share Allport's view that idiographic science, based on the analysis of single cases, is possible -- or, conceding that it is possible, that it is desirable or useful. For them, the intensive study of individuals is best left to clinicians and biographers. Rather, they seek to develop a universally applicable structure within which individual differences in personality can be measured and represented. For most investigators, factor analysis has been the royal road to the study of personality, because it seems to provide a rigorous mathematical technique for discovering the number of basic traits, and the relations between them.

The Language of Traits

A number of investigators have used factor analysis and related multivariate techniques to reduce the set of trait names to a manageable number (for reviews see Goldberg, 1981a, 1981b). First of these was Raymond B. Cattell (1943a, 1943b, 1945, 1946, 1957) who reduced Allport and Odbert's list of 4,504 stable characteristics -- what Cattell called the personality sphere -- to 160 by eliminating synonyms and terms which appeared to him and his linguistic and philological consultants to be closely related. To this he added a few technical terms not found in standard dictionaries (e.g., frustration tolerance, level of aspiration), bringing the list to 171 trait-names plus their antonyms. Cattell then obtained the correlations of each trait with every other trait, derived from a number of previous rating studies. These were then sorted into 62 clusters consisting of items showing high intercorrelations, which were then labeled as a single bipolar dimension consisting of an adjective and its opposite. Computers being unavailable at the time, the 62 clusters were still too many to handle, so related clusters were combined to yield a final core list of 35. Ratings on a new sample produced a matrix of intercorrelations which was factor-analyzed by hand, using large sheets of graph paper spread out on the floor (I'm not kidding about this!). This yielded 12 factors, which Cattell termed the "primary source traits of personality". A large number of studies performed since then, often employing computers for data analysis (thus permitting assessment of a somewhat larger list of trait- terms), have repeatedly found the same traits (Cattell, 1957; Hammond, 1973).

-

Cyclothymia vs. Schizothymia(i.e., easygoing vs. obstructive, cantankerous)

-

General Mental Capacity vs. Mental Defect (essentially, intelligence)

-

Emotionally Stable Charactervs. Neurotic General Emotionality

-

Dominance-Ascendance vs.Submissiveness.

-

Surgency vs.Desurgency (i.e., cheerful, joyous vs. depressed, pessimistic)

-

Positive Character vs.Dependent Character (persevering, determined vs. quitting, fickle)

-

Adventurous cyclothymia vs. Withdrawn Schizothymia (differing from the earlier entry in terms of adventursomeness vs. timidity)

-

Sensitive, Infantile, Imaginative Emotionality vs.Mature, Tough Poise (demanding, impatient vs. emotionally mature)

-

Socialized, Cultured Mindvs. Boorishness

-

Trustful Cyclothymia vs.Paranoia (differing from the earlier entries in terms of trust vs. suspicion)

-

Bohemian Unconcernedness vs.Conventional Practicality (i.e., unconventional vs. conventional)

-

Sophistication vs.Simplicity.

Cattell performed oblique factor analyses, so even these 12 primary traits may have been related to each other, and thus resolvable into a smaller number of secondary (or even higher-order) traits. Moreover, his factor- analytic technique, limited as it was by the primitive technology available at the time, left plenty of room for error to creep in.

"The Big Five"

Perhaps for these reasons, subsequent attempts to replicate his basic findings have typically revealed five factors rather than twelve (Borgatta, 1964; Digman & Takemoto-Chock, 1981; Fiske, 1949; Goldberg, 1980; Norman, 1963; Tupes & Christal, 1961). These factors, each defined by Norman (1963) in terms of four adjectives and their antonyms, are presented below.

The Big Five According to Norman (1963) |

|

Extroversion (Surgency) |

Talkative - SilentFrank, Open - SecretiveAdventurous - CautiousSociable - Reclusive |

Agreeableness |

Goodnatured - IrritableNot jealous - JealousMild, Gentle - HeadstrongCooperative - Negativistic |

Conscientiousness |

Fussy, Tidy - carelessResponsible - UndependableScrupulous - UnscrupulousPersevering - Quitting, Fickle |

Emotional Stability |

Poised - Nervous, TenseCalm - AnxiousComposed - ExcitableNot hypochondriacal - Hypochondriacal |

Culture |

Artistically Sensitive - Artistically InsensitiveIntellectual - Unreflective, NarrowPolished, Refined - Crude, BoorishImaginative - Simple, Direct |

This structure is highly stable: these five dimensions constantly appear from study to study, whether. people rate themselves or others, and whether the factor analysis is. orthogonal or oblique; and regardless of the particular scales on which the ratings are made, or the mathematical details of the factor-analytic procedure.

Later studies have essentially confirmed Warren's findings, although the characterization of the fifth factor has undergone some further evolution. In one early study (Fiske, 1949), Factor V was labeled as inquiring intellect -- not so much high intelligence as what the person did with whatever intelligence he or she had. Other studies labeled this factor intellectance -- not so much being smart as appearing to be smart. Norman, as noted, settled on culturedness. Later work by Costa and McCrae reinterpreted the intellectance-culturedness factor as openness to experience. It's this last label, shortened to openness, that has stuck. And it's openness, not intellectance or culturedness, that is measured by Costa and McCrae's NEO-PI personality inventory, which has become the gold standard for personality assessment.

Considerations such as these led Norman (1963) and Goldberg (1981) to suggest that the "Big Five" dimensions of extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness are the fundamental trait terms in the English language -- and perhaps in other languages as well. Thus, by 1963, and certainly by 1981, researchers had reached the end of their quest for what might be called "the Holy Grail" of personality research -- a list of the fundamental dimensions of personality, which can be used to capture the gist of a person's personality -- anyone, of any age, at anytime, and anyplace.

Circumplex Models of the Trait Lexicon

Recently, Wiggins (1979, 1980) has proposed a somewhat different solution to the problem of trait names. He began with an a priori classification of the entire list of trait names into six categories:

-

interpersonal traits, or qualities of social interactions which are based on considerations of love or status (e.g., aggressive);

-

material traits, or qualities of social interactions which are based on considerations of money, goods, and services (e.g., miserly);

-

temperamental traits, or styles of emotional responsivity (e.g., lively);

-

social roles, or one's role or status within social institutions (e.g., ceremonious);

-

character traits, or appraisals of behavior (e.g., dishonest);

-

mental predicates, or qualities of mind (e.g., analytical).

Within each category, Wiggins has sought to reduce the list of trait names by means of a set of advanced multivariate statistical techniques related to factor analysis. So far, he has completed work on the set of interpersonal traits. Essentially, he finds evidence for sixteen traits which form eight bipolar dimensions defined by an adjective and its opposite:

-

ambitious vs. lazy;

-

dominant vs. submissive;

-

gregarious vs. aloof;

-

extraverted vs. introverted;

-

warm vs. cold;

-

agreeable vs. quarrelsome;

-

unassuming vs. arrogant; and

-

ingenuous vs. calculating.

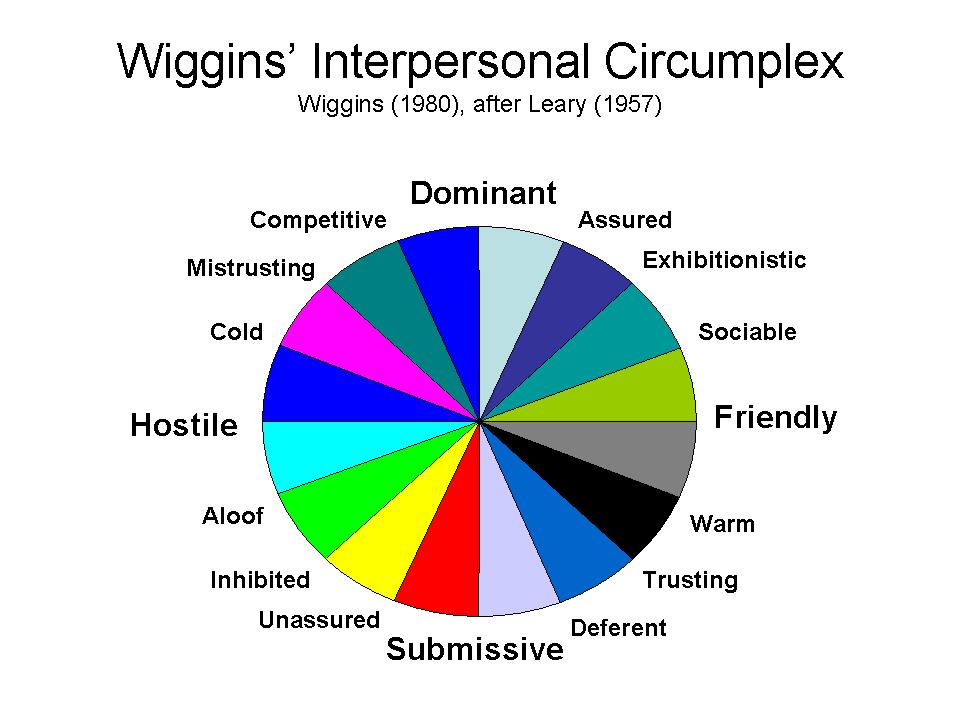

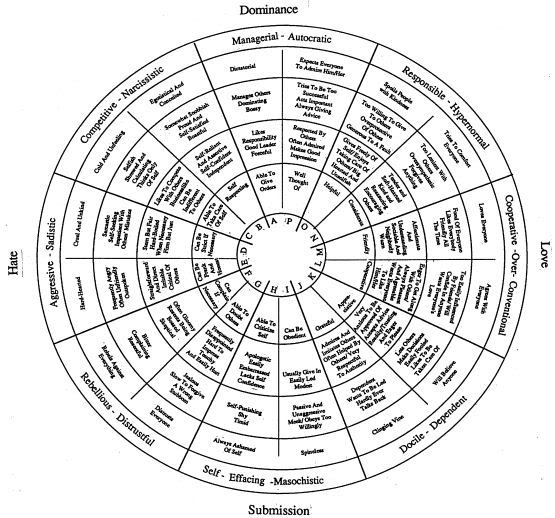

Interestingly,

the relations among these traits, when expressed

geometrically, form a structure known as a circumplex, or a

two-dimensional circular ordering in which the trait relations

are shown in terms of angles between vectors representing the

traits. Some traits, such as ambitious and lazy or extraverted

and introverted, are antonyms and are separated by an angle of

180 degrees representing a perfect negative correlation. Other

traits, such as ambitious and dominant or warm and agreeable,

are so closely related as to be almost redundant, and their

perfect positive correlation is represented by an angle of 0

degrees. Still other traits, such as gregarious and unassuming

or arrogant and aloof, are completely unrelated, as expressed

by an angle of 90 degrees. And finally, other traits, such as

ambitious and gregarious or introverted and submissive, are

positively but not perfectly correlated, as expressed by an

angle of 45 degrees.

Interestingly,

the relations among these traits, when expressed

geometrically, form a structure known as a circumplex, or a

two-dimensional circular ordering in which the trait relations

are shown in terms of angles between vectors representing the

traits. Some traits, such as ambitious and lazy or extraverted

and introverted, are antonyms and are separated by an angle of

180 degrees representing a perfect negative correlation. Other

traits, such as ambitious and dominant or warm and agreeable,

are so closely related as to be almost redundant, and their

perfect positive correlation is represented by an angle of 0

degrees. Still other traits, such as gregarious and unassuming

or arrogant and aloof, are completely unrelated, as expressed

by an angle of 90 degrees. And finally, other traits, such as

ambitious and gregarious or introverted and submissive, are

positively but not perfectly correlated, as expressed by an

angle of 45 degrees.

Wiggins argues that each of these traits can be conceptualized in terms of three facets of interpersonal behavior:

-

directionality (acceptance or rejection);

-

object (self or other); and

-

resource (love or status).

Thus, the relations among traits derived from ratings parallels the conceptual similarities among these adjectives, which is as it should be if our language means anything at all. Nevertheless, as Goldberg (1981) points out, a circumplex is a two-dimensional space, so Wiggins' list of eight traits actually resolves to two, affiliation (love) and power (status) -- or, as Wiggins himself noted (see the Lecture Supplement on "Psychological Development", the stereotypical Western gender-roles of agency and communion. Therefore, Wiggins' circumplex simultaneously incorporates two levels of description: a very economical but somewhat impoverished two- factor structure, and a rather more rich but still highly organized eight- factor one.

Wiggins'

work was an extension or earlier work by Timothy Leary (1957)

-- yes, the same Timothy Leary who advised people to "Turn On,

Tune In, and Drop Out". Work on the structure of personality

traits continues apace. The chief product of this work is

likely to be a concise vocabulary which permits what

personality psychologists have sought for a long time: the

efficient and accurate description of individual differences

in behavior.

Wiggins'

work was an extension or earlier work by Timothy Leary (1957)

-- yes, the same Timothy Leary who advised people to "Turn On,

Tune In, and Drop Out". Work on the structure of personality

traits continues apace. The chief product of this work is

likely to be a concise vocabulary which permits what

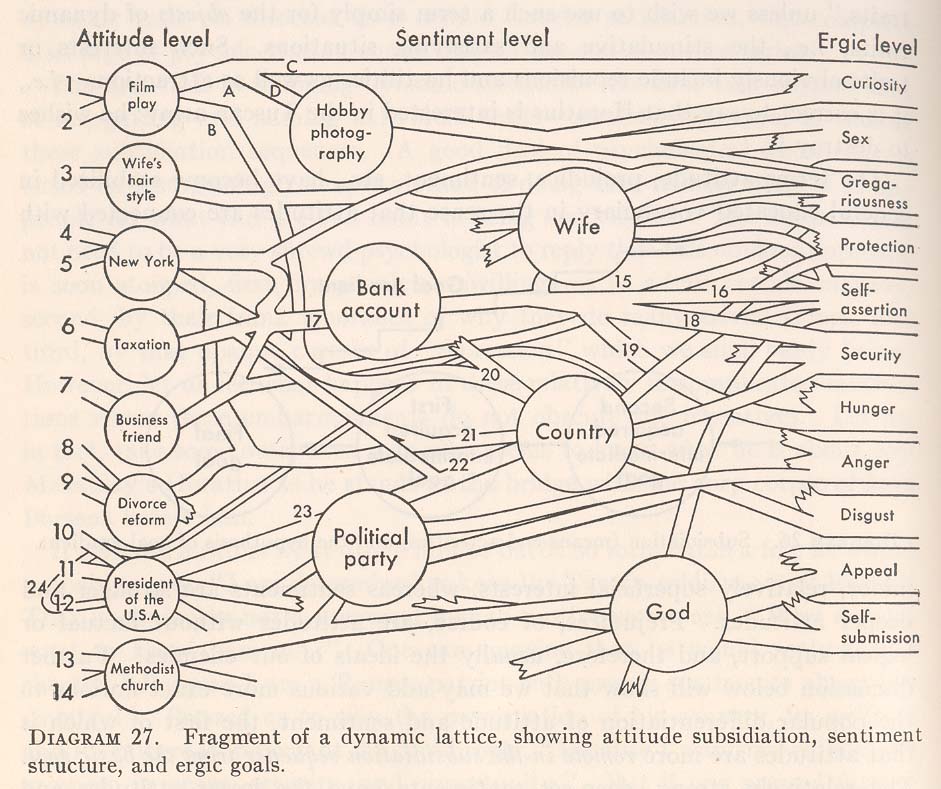

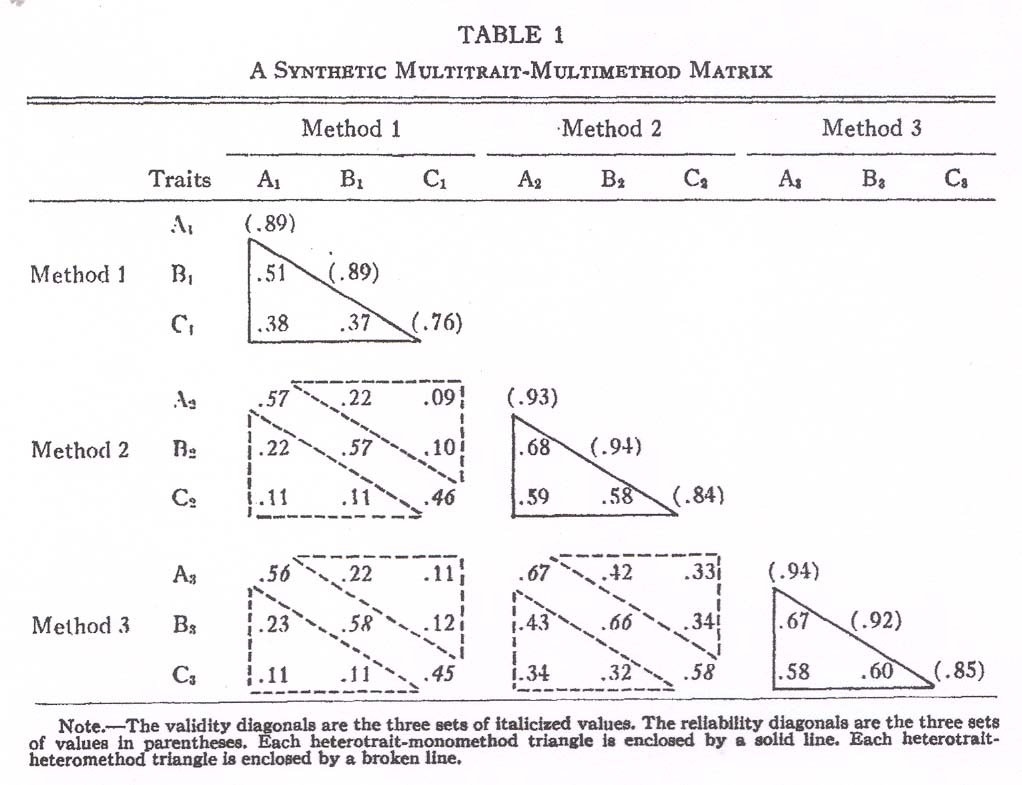

personality psychologists have sought for a long time: the