If we evaluated health care not on the achievements of modern medicine, but on what remains to be achieved, what would be missing? Now imagine a single parent with both a young son and daughter entering into a county hospital. The parent is unemployed and uninsured, but both her little ones have been coughing phlegm for the last 48 hours. The kids need medicine, but the parent doesn’t speak English, so what do we do? Encapsulated in the concept of “cultural competence,” speaking to the family through a translator phone and treating the symptoms with medicine are incomplete answers. They ignore the inherent social and cultural complexities unique to each family’s story.

In health care, we see that patients receive medical support, but beyond treatment of the symptoms, unspoken concerns remain largely unheard. For example, an important component of preventative care involves enriching the health beliefs held by cultural groups, such as Latino, Asian, and African-American communities — yet it is often disregarded. In a country growing in ethnic diversity and with health care reform changing the foundation of medicine, cultural competence is not enough to address our increasing national ethnicity.

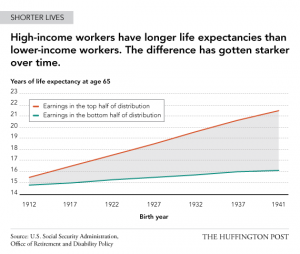

Previous studies by the US Social Security Administration show the worsening of equality between the rich and the poor. Amidst a century of technological, educational, and cultural revolution, the rising life expectancy of low-income workers do not equate with that of high-income workers. This disparity suggests a necessary shift to change how we manage social and health inequality.

Dr. Tervalon and Dr. Murray-Garcia respond to this issue by promoting a shift in the perspective of health care toward cultural humility. Cultural humility is the “lifelong commitment to self-evaluation and self-critique, to redressing the power imbalances in the patient-physician dynamic, and to developing mutually beneficial and non-paternalistic clinical and advocacy partnerships with communities on behalf of individuals and defined populations.” Cultural humility stands for a multidimensional perspective that incorporates patient stories, race, language, and unheard concerns in the body of medicine.

In a recent discussion with Rhonda Ngom, she spoke about the issue of physicians disregarding her martial name, “Ngom,” because of the inability to pronounce the African-descendant word. She says, “If doctors fail to address me by my name, immediately, the cause is lost. How can my doctors treat me if they don’t treat me.” Mrs. Ngom recognizes the value in empathy between the patient and the doctor, and to that end, advocates for more conscientiousness of race and culture in medicine. From her experiences, she draws on an inherent issue in ignoring the often implicit details of patient care.

In a world where health care reaches to all walks of life: young, old, male, female, poor, and rich, a growing disparity among how we treat culturally rich individuals must be addressed. Health accounts for more than treatment of the disease or the symptom. In a holistic perspective, health care is the recognition of the individual that lives and breathes with his or her own unique experiences. In recognizing the culture, language, and story held by each person in health care, the next important issue at hand is to address the social needs of the patient — only then can we move forward in health care.

Citations

- Are You Practicing Cultural Humility? – The Key to Success in Cultural Competence from California Health Advocates <http://www.cahealthadvocates.org/news/disparities/2007/are-you.html>

- Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education by M. Tervalon and J. Murray-Garcia from PubMed by the National Center for Biotechnology Information and the US National Library of Medicine <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10073197>

- JMP Key Vocabulary from University of California at Berkeley School of Public Health Joint Medical Program <http://jmp.berkeley.edu/curriculum/jmp-key-vocabulary>

- Socioeconomic Stress Leaves Lasting Scars (INFOGRAPHIC) from Huffington Post The Third Metric by TheHuffingtonPost.com, Inc <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/08/15/socioeconomic-stress-_n_3761526.html>

Article by Telly Cheung

Feature Image Source: New Jersey Doctor-Patient Alliance