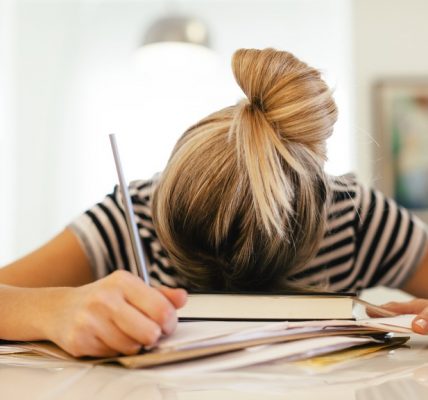

As an adolescent, I suffered from episodes of migraines. I visited several doctors and a neurologist, I even had an MRI, and somewhere along that route I was prescribed medication. But not one of these doctors either speculated or inquired about my diet, or the possibility that I may not be drinking enough water to meet my body’s needs. I had initially made a mistake by thinking that I was deficient in other nutrients such as protein or iron. After all else was ruled out, I finally realized my water-drinking habits were at fault, and the nutrient I had been lacking was the least (and last) suspected.

I now treat my headaches with the best method—prevention—which constitutes a habitual eight to ten glasses of water a day. But besides warding off headaches, what are some other benefits of sticking to regular fluid intakes, and how much of the stuff do you really need? I’ve found recently that as the use of prescription medication as the first resort increases, we tend to forget that the regulation of essential nutrients (such as water) may be helpful for averting our illnesses and even rehabilitate our health.

Water serves many important purposes in your body. Your body is 60% water. Water functions to filter toxins out of your vital organs, provide a moist environment for your ears, nose, and throat, lubricate your joints, create saliva, regulate body temperature, transport nutrients and waste products, and do much more. Water also helps reduce and relieve cramping while working out or during menstruation by helping muscles contract and relax. As fluid loss continues throughout the day in the form of urination, sweating, evaporation, and other metabolic processes, water needs to be constantly replenished.

Water is actually needed in larger quantities than any other nutrient: for men, the recommendation is 3.7 liters per day, and for women, 2.7 liters. Most of these liters come from the fluids that you drink, but about a quarter of it comes from food. Besides the “eight-a-day” guideline, I’ve found the easiest method to calculate your water needs is to drink half your body weight in ounces: for a 150 lb. person, this means at least 75 ounces, or about nine eight-ounce glasses of water. This can include beverages like milk, juice, or soda; however, caffeinated drinks such as coffee, tea, and soda, are diuretics and can actually cause water loss.

Your water needs can increase with intense exercise, environmental factors, and health status. If you exercise (which you should!), you need to consume more water to compensate for the water lost through sweating. Drinking an extra sixteen ounces combats water loss during short-duration exercise, but it is important to continually drink during and after a workout. Regulating body temperature in hot weather or at high altitude—which causes rapid breathing and more frequent urination—also depletes your water reserves. Drinking plenty of water is also crucial when you are sick, since fluids help regulate body temperature.

So what happens if you do not meet your body’s fluid requirements? Some of the immediate effects are obvious and common: dry mouth, chapped lips, thirst, or even a false feeling of hunger. However, there are signs you may not associate with dehydration that occur from dehydration such as urinary tract infections, general lack of energy, or frequent headaches. Other, more serious, complications like constipation can also appear. Dehydration can even contribute to the development of colon cancer, which may result from the lack of insoluble fiber and water to help move food through the digestive tract and slough off mutated cells.

Water is also is a huge participant in the production of hormones such as serotonin and melatonin. The lack of serotonin may cause depression, and the lack of melatonin may cause insomnia. Water also helps ensure that your immune system is working properly: it helps in the production of lymph, providing a gateway for your white blood cells and other immune cells to travel through the body to fight off illnesses, which I know is very important to busy, stress-prone, and therefore sickness-prone students.

Another complication associated with dehydration is the infamous hangover headache, actually the result of brain cell dehydration that can also be caused by alcohol. The best preventative action is, of course, to not indulge in drinking in the first place, but even with a few of-age sips of an alcoholic beverage, the next morning can sometimes be a pain in the head. Next time you have a hangover, drink it away, and make a mental note to stay hydrated before and during activities that promote water loss.

Just like my episodes of headaches (which, by the way, have greatly subsided if not completely ceased), I’ve found that many illnesses or health problems can be prevented, or at least ameliorated, by adopting water-guzzling habits. It’s crucial to regulate water intake just as you do with other major nutrients. If nothing else, ensuring that you are meeting your water needs will bring you closer to discovering how it feels to be healthy and create a clean platform to better understand your body and your health.

Article by Lauren Tarver

Feature Image Source: ScienceDaily